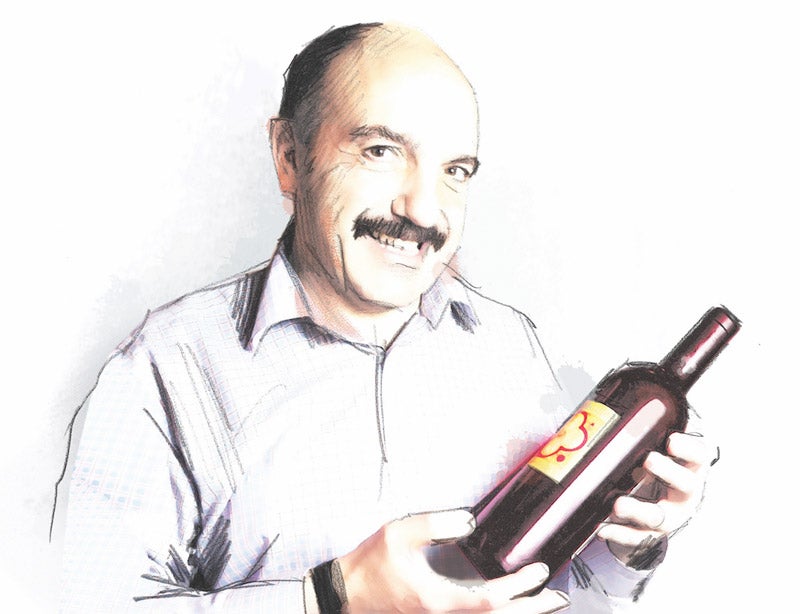

By my early 20s, when most of my friends had a pretty clear idea of what career they were going to follow, I did not have a clue what I was going to do later on in life. While my parents genuinely loved their three children, they spent most of their time at war with each other and, as a consequence, did not pay huge attention to our education. Personally, I did not care much for school; or rather, I saw school as a place where I would have fun and entertain my fellow pupils. The result was that I left school at the age of 16 with no real qualifications. For a few years, I drifted into all sorts of manual jobs that, for the most part, I hated. On more than one occasion, I was concerned for my future. But being a bit of a dreamer, I imagined that somehow something positive would happen and that everything would be all right in the end. It never occurred to me, though, that I would later dedicate so much of my time and energy to becoming a professional sommelier.

Indeed, at home during my youth, wine was never all that much of a topic of conversation. Of course, my mother and father drank wine—ordinary wine, that is—every day with their meals, like most French people of that time, and I was regularly given a version of it highly diluted with water. But other than that, my family had no connection to the world of wine and certainly not ne wine.

I was born not far from Lyon, in the industrial town of St-Etienne, and grew up in its suburb, in the little town of Firminy. Beaujolais and the northern Rhône are not that far from St-Etienne, and the Côtes du Forez AOC is even nearer. But St-Etienne (and by extension Firminy) is just not a wine area, and since we did not go on holiday very often, I had little opportunity to discover wine regions or to be exposed to the intricacy of ne wine. The only thing that would make me think about wine was watching the tour de France on TV, when the racers were riding through some of the famous wine regions.

The first time I really took notice of the word “sommelier” was when I was 19 and a local lady, Mme Danièle Carré-Cartal, won the title of Meilleur sommelier de France. That made her a local celebrity, and many people were in awe of her achievements. That did not make me want to become a sommelier, but I was certainly very impressed by her accomplishment, without really understanding what she had done or what a sommelier was.

Falling in love with England—and wine

At about the same time, I came to England for a football (soccer) match, and it was in England that I would really take wine seriously. I’d traveled to Liverpool to support my football team, the “Greens” of St-Etienne, in a European Cup match against the “Reds” of Liverpool. But during that trip I fell in love with this beautiful country. To the complete astonishment of all my friends and family, I promised myself that I would return and make my life there.

My first job in the UK was as a kitchen porter on the Isle of Man. Then, after a few weeks, when my English had improved a bit, I found a position as a waiter in a hotel in the new forest in the south of England. Because I was French, people thought I knew a lot about restaurant service, but in fact I knew very little and was doing my best to learn quickly on the job, which was for me a completely new profession. I stayed there for six months and then decided to go back to France to learn more about gastronomy.

I enrolled on a short, six-month cookery course, funded by the French government, in order to become a chef. After completing the course, I worked for two years in France as a Commis de cuisine in the kitchens of two well-regarded restaurants (one of them had a Michelin star). In addition, I passed the national French cookery exam (CAP de Cuisine), as well as the national French waiter exam (CAP de Restaurant).

Armed with my new expertise and my two professional qualifications, I decided it was time to return to England for good. My aim was to work my way up to become restaurant manager in a ne-dining restaurant. However, Victor, the manager of the restaurant where I had just restarted my English career, again in the new forest, gave me the position of sommelier, even though I had only basic wine knowledge at that time. I took the role very seriously and decided that I should also study for the French national sommelier exams (CAP de sommelier, later replaced by a qualification still in existence today, the Mention Complémentaire de Sommellerie) in the hope of completing my all-round gastronomic education. It was a practical solution, since I could prepare for this exam in England and only needed to go to France for a week in June to take it. I passed the exam—not brilliantly, but at least well enough to get the official sommelier qualification under my belt.

Turning point: the first competition

A year later, I moved to?another restaurant, still in?the south of England, but?in surrey, where I was?employed as head waiter. One day, a leaflet came? through the restaurant postbox advertising the?launch of a new competition for sommeliers, testing their skills and knowledge of French wines (UK best sommelier for French wines). I had no intention of applying, but Jean-Yves Morel, the owner of the restaurant, insisted that I entered. I put in quite an effort to prepare for it, and to my amazement I qualified for the UK national final, where I ended up coming fifth. Although I would realize a few years later that the overall level of this competition was quite low and that finishing fifth was not such a great performance after all, the experience marked a real turning point in my career. A few months later, I decided that sommellerie was to be my profession. I promised myself that I would be ambitious and aim for the highest level I could possibly achieve, reasoning that, in life, if you want to jump 6ft (1.8m), you should work toward jumping 6ft 6in (2m) or even more.

From that moment on, I was completely focused on succeeding in the field of wine and sommellerie. I started to plan for sommelier competitions and wine exams with military precision. Re-entering and winning the UK best sommelier for French wines got me noticed by a head-hunter who put me in touch with the famous Chewton Glen hotel in the new forest.

In March 1988, I took up my new position of head sommelier at Chewton Glen, where I enjoyed six and a half happy years, meeting my wife Nina, who would become my greatest supporter, along the way. It was at Chewton Glen that my career really took off. While working there, I became a Master sommelier, won several national sommelier competitions, and started to achieve good results in international sommelier competitions (finishing second in the best sommelier in the world 1992 and winning the best international sommelier for French wines 1992). I also gained my WSET wine diploma and began my quest to become a Master of wine.

The MW challenge

The Mw examination was an enormous challenge for me. Despite my sommelier credentials, I realized that if I wanted to be taken seriously by the UK wine trade, I had to become an MW. And so I became obsessed with passing the exam.

The MW is very different from the Master sommelier qualification or sommelier competitions, which are based on issues such as factual wine knowledge, oral blind tasting, food and wine pairing, cellar management, and wine service—all fairly logical disciplines for someone seriously dedicated to serving wine in a restaurant (which was the case for me when I was at Chewton Glen). The MW is a more academic examination, in which the candidates have to demonstrate and argue in a logical way through a series of essays and one dissertation their understanding of the world of wine in general. Even the blind tasting part is quite different. The candidates are, of course, requested to identify as many wines as possible, but not by going through tasting descriptions and, rather, by clearly justifying their choice through sound reasoning. It took me a while to understand the system and prepare for it, so I followed the course for a few years before attempting the exam. I struggled with the theory part and had to resit this section, since writing essays was alien to me. On the advice of the institute of Masters of wine, I began reading The Economist for the clarity and quality of the articles in its house style, and to my surprise the clever simplicity of the writing did help me understand how to write and argue an idea well.

I am also particularly grateful to several MWs—Jane Masters, Richard Bampfield, Lance Foyster, Mark Pardoe, Richard Lashbrook, and a few others—who spent a lot of time mentoring me. They showed me great kindness and patience and helped me conquer my Everest.

Fortunately, I passed the blind-tasting part of the exam first time, gaining the Bollinger Cup for being the best taster in my year along the way—but not without a few scary moments. Two months before the exam, during a blind- tasting training session with eight red wines, I was the only one of the 40 or so students to get them all wrong. That day, I felt so humiliated, especially since the student sitting next to me had an admirably high success rate with those eight wines and was quite boastful about it: I felt like crying. I promised myself that this would not happen again and that I would be ready for the big moment.

I have to say on the matter of blind tasting that I get very annoyed when I hear or read of people who tell us only of their blind-tasting success stories. As anyone who has been involved for a long time in that field—as a participant or as an examiner—will know, it just does not happen like that. Even the very best tasters have terrible days. In his book, The Official Guide to Wine Snobbery, Leonard S Bernstein compares blind tasting to golf, and he is so right. Some days it works well, but other days nothing works, and for some reason it seems that these days occur more often!

Thinking back to my time at the Chewton Glen hotel, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it was a very exciting place to work. The hotel had a Michelin star for its restaurant at a time when few restaurants in the UK had one. In addition, the owner Martin Skan was extremely passionate about wine. When I took up my position as head sommelier, the wine list was already excellent, with plenty of iconic wines and even many from the new world (unusual in ne-dining restaurants in those days), which made it an ideal way for me to learn about them. The hotel used to host some very special wine dinners. One I particularly remember was the Château Latour dinner. A few years earlier, Chewton Glen had bought directly from the château an Impériale of 1961 Latour, which had been sold to the hotel on the condition that it would be used for a special Latour dinner. The dinner took place in 1989, and Hugh Johnson was the guest speaker. Jancis Robinson Mw, her husband Nick Lander, and the then-manager of Château Latour were also there. Another vintage of Latour, a vintage of Les forts de Latour, and other delicious wines, such as a special vintage from Champagne Pommery, a superb Pavillon Blanc de Château Margaux, and a magnificent Château d’Yquem also formed part of this event. The dinner was limited to 40 people to make sure everyone would get a fair quantity of the ‘61 Latour. I was very excited at the thought of serving Hugh and Jancis, two of my wine idols, but I also became very nervous and worried. What if the ‘61 Latour was corked? What if I dropped and broke the Impériale of ‘61 Latour? It was the linchpin of the dinner, and we only had one. Fortunately, all went well, and I was able to sample all the wines, including the amazing 1961. It is events like this that make the job of sommelier so special and so rewarding.

The birth of Hotel du Vin

During my period at Chewton Glen, I had become friends with the managing director, Robin Huston, who was also quite interested in wine. Robin had plans to start a hotel of his own and asked if I would become his business partner in the venture. I was taken aback because I had never showed him any interest in wanting to be a hotelier. In fact, at the time, Nina and I had dreams of moving to Napa Valley, California, where I would work in the wine industry. In addition, Nina and I were in negative equity, with a 100 percent mortgage loan of £52,000 for our at, which was by then worth only £34,000 if we had wanted to sell it; so I had very little cash to put into any business.

Nevertheless, after some persuasion, on the advice of Nina, I accepted Robin’s proposition and managed to raise a bit of money by selling my car and borrowing money from Nina’s parents, resulting in me having enough cash to put a deposit toward my shares. Robin and I started to work on the project in earnest, and it was all very exciting. We met regularly to finalize the concept, decide on the name of the business, and go through all sorts of details. The main idea was to create a hotel-restaurant with elements of luxury, such as great bathrooms with powerful showers and very soft towels, comfortable beds, delicious, but uncomplicated food, well- selected wines at reasonable prices, and extremely friendly service, but cutting down on all we thought was inessential and also expensive, such as valet parking of guests’ cars, a bedroom turndown service, and overelaborate food and wine service. In effect, our aim was to produce the top mid-market hotel. Today, it seems normal and obvious, but back then hotel- restaurants like this were not the norm. During our months of preparation, we had to be very secretive, since we did not want our boss and colleagues to know of our plans. Not being able to talk freely about it made it quite tricky, since we needed to find investors. Eventually, however, we did find those investors, and also a bank loan, and in October 1994 we were able to open the first Hotel du Vin in Winchester.

To raise more money, we set up a sponsorship scheme for the bedrooms of the hotel. Each room could be named for a wine producer for a fee. Depending on the size of the room, each company paid us from £4,000 to £6,000 for three years, but in return that company was given six “room nights” free per year (in its own room when possible) and a 20 percent discount on the food if they used the restaurant or function room. They could also bring their wines with no corkage charge for any event they would hold at the hotel, and of course their room was named for their company. It took a bit of convincing, but finally all of our bedrooms, our banqueting room, and the lounge were sponsored, so we had the Pol Roger room, the Laroche room, the brown brothers room, the Beringer room, the Villa Maria room, and so on.

We worked extremely hard, and Hotel du Vin took off like a dream. Luck was on our side, and perhaps it was also a question of right time, right place, right product. Whatever the reasons for its success, we never looked back.

At Hotel du Vin we hosted wine dinners, too—in fact, quite a lot of wine dinners by the time we had a few outlets, since we would do a wine dinner almost every Sunday in rotation, in a different Hotel du Vin. Those wine dinners bring back many great memories of meeting fascinating wine producers and tasting amazing wines. It was for me very exciting to set them up and organize them. One day in the mid 1990s, I read a report by Jane Macquitty, the wine correspondent for The Times and a good friend of mine. She had just reviewed the main commercial wine brands and given them marks out of 20. I don’t remember all the scores, but most of the famous wine brands had obtained marks well below ten points, so in effect much less than the average. I thought that was interesting, so I asked Jane if she would mind coming to Hotel du Vin, Winchester, to do a wine dinner at which we would serve some of these “dinosaurs” of the wine world and put alongside them wines of similar prices but that we thought had more character. Jane accepted with great enthusiasm, and we quickly agreed on the famous brands and the alternative wines to go alongside them to show on the evening. Normally when I organize a wine dinner, I deal with one or more on-trade wine merchants and arrange for the wines to be delivered a week in advance. However, in this case I knew I would have to go and buy all the mainstream wine brands in a shop, since the wine merchants I dealt with did not stock them.

Anyway, a few days before the event, I found myself in the wine aisle of the big supermarket near where I lived, filling my cart with a dozen bottles each of blue nun, Mateus Rosé, Piat d’Or, and a few more similar wines. Walking toward the checkout, I met two of my neighbors who stopped to say hello. I could have died with embarrassment, and I did not know what to say or to do. I can easily imagine what they must have thought when glancing at the contents of my cart: “Here is the supposed wine guy, who may know about one wine, but look what he drinks at home!” after a quick (very quick) chat with them and paying, I prayed that I would not meet anyone else I knew on the way to my car. Who thought that organizing wine dinners was risk-free?

Lessons from a Montreal op

If my time as co-founder and co-owner of Hotel du Vin was very happy and successful, I also had challenges while I was there. In the early part of 1999, I started to write a book on wine tasting. I did not know how to use a computer at the time, but I had stupidly agreed with the publisher to hand over the manuscript by November 1999. Through evening classes I learned to use a computer, but as I was working my normal week in the hotel business and had to write the book in my spare time, and my son was born in 1999, it was a very busy period. I got behind with the book and finished it only in May 2000. At the beginning of the year, I’d also decided to take part in the best sommelier in the world contest, which was to take place in Montreal in September 2000 (this competition occurs every three years). I only started to prepare from the beginning of June, when I had finished my book. I arrived in Montreal for the competition as the firm favorite, because I was by then MS and MW, I had finished second when I last did the competition, and in between I had won the best international sommelier for French wines and the best sommelier of Europe. Not totally by coincidence, my book was coming out the same week as the competition, and a Canadian distributor had ordered a fair few copies for the bookshops of Toronto and Montreal. I had agreed to stay a few extra days in Canada to do some signing sessions. The closer the day of the competition came, the less confident I felt, and by the time it started, I was totally exhausted. I hadn’t taken a holiday for 18 months, and I’d spent all my spare time writing a book, adjusting to fatherhood, and then rushing the preparation for this important event. It did not take long for me to realize what I already knew deep down: I was out of shape and not up to it. Not only did I not win the competition, but I did not even reach the final, and it all ended for me in a complete op! Olivier Poussier of France took the prize.

I was extremely disappointed, but that experience taught me a lot. I realized there was no point in blaming the timing of the book, or any other circumstances, or bad luck. At the end of the day, I was the one who had chosen to write my book at that time, and I was the one who had mismanaged my preparation for the competition, such as omitting to train for certain important aspects of it. In life, we have to take responsibility for our choices and to accept setbacks as learning tools to progress and improve. That experience made me more determined to re-enter the competition and to win it. Of course, it is never enjoyable to underperform, but it can happen to anyone, even the most successful people in business or in sport. The important thing is to come back stronger from it.

By 2004, we had owned Hotel du Vin for ten years and had built it into a group of six successful hotels. We were approached that year by the owners of Malmaison, another small group of hotels and our closest rival in quality terms. Their offer was good, and we took it. After that, I spent a few months traveling and relaxing in wine areas, and then in 2005 I enrolled for the Bordeaux wine MBA, which I completed in March 2007.

In 2006, Nina and I decided that we would restart a hotel. We missed being hoteliers, but this time we didn’t want to build a group—simply a small boutique hotel in the new forest, where we have spent most of our adult life. Unlike all the Hotels du Vin, which had a French bistro-style restaurant, at Hotel TerraVina we took our inspiration from California. The restaurant has an open kitchen, and we tried to make it feel a bit Californian, serving a take on California cuisine.

Although we have achieved a lot of the things we set out to do, it hasn’t always been easy. The economic recession, which has been particularly hard for businesses outside London, started around a year after we opened, in September 2008, and has continued until now, so it has been with us for most of the hotel’s existence. When we started, there were very few competitors nearby, but now there are many more, and we are all sharing a smaller slice of the pie due to the recession. Again, in life you have to deal with the less good times, and Nina and I have certainly learned (and continue to learn) much from this tough period and the numerous challenges we have encountered along the way.

The road to Santiago

In 2007, a month after I had completed the wine MBA, I finished second in the best sommelier in the world 2007, in Rhodes, Greece. To finish the Wine MBA and prepare for the World Sommelier Competition was a bit of a juggle, but somehow I managed fairly well. As Hotel TerraVina was then being refurbished and had not yet opened, I had just enough time to work on both projects, especially with Nina taking most of the hotel project on her shoulders.

At that time, we already knew that the Best Sommelier in the World 2010 was going to take place in Santiago de Chile in April of that year. Having entered this competition five times previously, and having just finished second again (I finished second twice and equal second once), I hesitated about doing it again. But not for long. Of course, I would have to win the UK selection first, but I was determined that I would prepare like never before and do my utmost to be the winner in Chile among the 51 candidates each representing one country.

To help me prepare for the World Sommelier Competition 2004 and 2007, a friend of mine, Bob Niddrie, a retired top accountant from KPMG whom I knew from my time at Hotel du Vin, where he was our non-executive director, had coached me and organized for friends and some of my sommelier colleague to come regularly to see me and set up exercises for me and give us their feedback. Of course, my wife Nina was always deeply involved, and it was she who would, for months on end, prepare the blind-tasting sessions taking place at home and who would share with me her very useful thoughts on all aspects of my preparation. She was the one who shared most closely with me the highs and lows of the competition preparation, and she was a great support throughout.

The competition lasts three days. On the first day, the 50 or so candidates start at the quarter-final stage, which is composed of a long written questionnaire on wine, spirits, and any other beverages, such as beer, sake, mineral water, coffee, and tea, then a written blind tasting of wine and spirits, and finally a service exercise run individually in front of a jury. The top 12 candidates go through to the semi-final, in which they must answer another long theory questionnaire. Next, they have to blind-taste some wines and spirits but this time orally in front of a jury; then one by one in front of another jury, they have to taste a dish and recommend wine for it, as well as serve wine to a table of eight judges with a few traps thrown into the exercise for good measure. I should note that, at all stages (quarter-final to final), all the tasks are rigorously timed. On the third day of the competition, the final takes place on stage in front of a live audience of several hundred people, including myriad official cameramen and photographers, and the judges. The three finalists are announced just a few minutes before the final starts, and one by one (the other two are kept in complete isolation) each finalist performs a series of tasks lasting about 45 minutes.

In the 2010 final, the first task was to prepare a cocktail and serve some Champagne to a table (4 minutes). Next, we had to create a menu to match a set of international wines and beverages we had just been given (6 minutes), before decanting and serving a magnum of red wine for a large table (6 minutes). For the fourth task, we had to correct a wine list dotted with errors put on a large screen for the audience to see (4 minutes). Then came the dreaded blind tasting of four wines and eight spirits (15 minutes), which is hugely stressful in front of an audience. And finally we had to identify famous worldwide wineries or well-known wine countries from a series of slides displayed on the large screen (3 minutes).

Roughly two years before the 2010 competition was due to take place, I decided to reassess completely the planning of my preparation and to go much deeper than I had previously done. My good friend Bob had done a great job as a “coach” for the past two competitions, but I wanted some fresh ideas.

This time I enrolled two coaches. Nick Twyman, a professional business coach, coordinated and oversaw the whole preparation; and Rebecca Williams, who joined us later (Nina knew her from our son’s school), was my second coach and worked more on the mental aspects of my preparation. In the past, I had engaged a sports psychologist, and that did help me, but I really liked how Rebecca understood my needs—she “got” me and what made me tick, and she cleverly found ways to help me control my nerves. I also enlisted the services of professionals—for instance, I worked with a memory expert to help me remember the dauntingly large number of facts involved in the theory section. Many sommelier friends regularly tested me on all sorts of relevant exercises, and two in particular—Dimitri Mesnard MS and Xavier Rousset MS, former sommeliers of mine at Hotel du Vin— spent a large amount of time setting up difficult tests and gave extremely valuable feedback. My own Hotel TerraVina team, especially the two then-sommeliers Laura Rhys MS and Laurent Richet MS, participated actively and set up countless blind tastings of wine and spirits for me.

In addition to the daily long hours of revising the theory and practicing the blind-tasting of wines and spirits (for many months prior to the competition), I practiced my wine service for many months through regular exercises such as decanting a bottle just prior to evening service. I must say I have always done wine service at Hotel TerraVina but never fully, since I have a team of sommeliers. I just take the pressure off them during busy times, but a big part of my role is to greet guests and supervise the overall service. Therefore, I became more involved again in recommending and serving wine at the hotel. In fact, two months before flying to Chile, I told my two sommeliers, Laura and Laurent, that each evening I would do the wine service fully, and they would be there just as backup in a funny reversal of the roles. I also asked João Pires (then head sommelier of Gordon Ramsay) and Diego Masciaga (the general manager and director of the Waterside Inn) if I could work some sessions with them as a commis sommelier but stressed to them both that it was crucial that I was put under real pressure and not given a cozy time. My time in both places proved hugely beneficial.

Finally, my team organized two extremely tough blank repetitions (practice runs) of the competition. We did not want these to take place at Hotel TerraVina, since it would have been too familiar a surrounding, and my team wanted to include some people I didn’t know in order to recreate the conditions of the competition. One of the trials took place in a club in London three months before the event, and the second at Chewton Glen four weeks before the event. I made plenty of mistakes on both occasions, but I learned so much. Both trials proved of enormous value and were to pay great dividends in the real competition.

Even though friends like Dimitri and Xavier very generously gave their time and expertise free, I had quite rightly to pay some of the other members of the team, as well as purchasing the very large number of bottles of wines and spirits for my blind-tasting training, buying a few outfits for the competition, and covering all sorts of other expenses. Therefore, to prepare properly for such a project can be very costly and I easily spent more than £20,000 in the months leading to the final. To help with the finance, I obtained some sponsorship money from two wine and spirit companies we use at the hotel.

Final triumph

I arrived in Santiago de Chile better prepared than I had been for any other sommelier competition. Still, you never know what will happen, and even if I performed brilliantly, it only needed someone to do a little bit better for me to finish second again. I started the competition relatively tense, but I did enough to be in the semi-final fairly comfortably. All the favorites had made it to the semi-final, along with a few unproven candidates, so it was now that the competition really started. From that moment on, any mistake could have important consequences and potentially close the door to the final. As soon as I finished the semi-final, I felt quite happy about how the day had gone. I thought I’d been fairly consistent overall. However, the following morning, a few hours before the final was due to take place, I went for a walk with my friend Paolo Basso, who was representing Switzerland and who was also one of the favorites. Since the finalists are announced only ten minutes before the final, we did not know if we would be in it. The more we discussed what we had done in the semi-final, the more we worried and the more we thought we would be watching the final rather than taking part in it. We should not have worried!

Paolo and I were announced as finalists, along with David Biraud of France. I drew number three and so had to wait in isolation for an hour and a half for my turn. Some candidates do not like that and would rather be the first or the second to go on stage. But I loved it. It gave me time to psych myself up, to prepare myself mentally. All the time I was waiting, I kept saying to myself, “Just go out there and enjoy it, and don’t worry—it is only a competition. You are not important, Gerard, it is the people in the audience who are important. Give them a lot of pleasure, and have fun, Gerard!” I just wanted to get rid of all the stress. My wife Nina and my son Romané (who was ten years old then) were in the audience with a Japanese TV crew filming them to see how they would react while I was performing. I completely blocked that from my mind, and once the first two minutes were over, I managed to relax and enjoy my time on stage. Ten minutes after the final, I was declared the winner. David finished third and Paolo second. (For the next edition, in Tokyo in 2013, I was the master of ceremony presenting the finalists to the audience and so could enjoy the brilliant performance of my friend Paolo, who went on to be named as the winner.)

For me, the feeling that came from achieving this longheld dream was really special, and to share it with my son and my wife who had supported me for years was really magical. I have to say I don’t remember much of the evening after the 2010 final—except that my son dropped the trophy. But since it is a huge silver Champagne bottle, it simply got a little dent that made it all the more special!

Of course, the role of a sommelier is not just about competitions. I know many sommeliers who never enter competitions but who do their job brilliantly. I also know a few competitive sommeliers by whom I wouldn’t really enjoy being served. For me, a great sommelier must be extremely adaptable to the many different types of customers and situations their restaurant will present. The sommelier must understand that some customers are very traditional in their tastes, some very adventurous, and some may want to impress their guests. But others will know little about wine and are really worried about it. It is also hugely important for the sommelier to appreciate carefully the budget the guests have reserved for the wine. Using all this information, and armed with a very friendly and extremely positive attitude, the sommelier should make some suggestions that match the personality of the guests, their budget, and the situation (type of food and occasion). The idea is for the sommelier to provide a lot of pleasure and to make the guests want to come back again and again. Of course, having a wide wine knowledge, being a great taster of wine and food, being able to buy well and sell well, managing the financial aspect of the cellar properly, motivating and training a team, and being a great ambassador for the producers are all important aspects of the job. But for me, the role is, above all, to ensure that the customers have a wonderful and very memorable experience of wine and service.

A life beyond imagining

Very early on in my career as a sommelier, I understood that learning about wine (enrolling on wine courses, reading wine books and wine magazines, tasting wine regularly), working on food and wine matching, and practicing wine service and customer relationships were indispensable in progressing my career. Traveling as often as possible to wine areas to meet the producers was also crucial. Wine regions are normally lovely and enjoyable places to visit, and most wine producers are very proud to show their vineyard and winery and let you taste their wines. For more than 25 years, I have spent several weeks each year doing just that. Of course, I remember fondly many of my visits, and not just those at iconic estates. Like every wine professional, I am regularly asked by non-wine people to name my favorite wine region. It is an impossible task, since for me most wine regions of the world are fascinating and unique and all offer great sensations and emotions. But if I had to choose only one region, I have to say I would most probably go for the island of Madeira. The island is beautiful, of course, but beyond that, drinking vintage Madeira, more than 100 years old, from Blandy or d’Oliveira, is just an incredible experience. It is as if we were drinking history and is totally magical.

I have been a sommelier and then a sommelier/hotelier, coupled with other activities, for a long time now. But I still love it. This profession has given me so many opportunities. For years, I have studied wine with a passion, and that has pushed me to learn more about related topics such as geography, history, geology, chemistry, biology, public speaking, and more. I have also met wonderful people from whom I have learned a lot and who have helped me develop as a person. Some of them have also become great friends. I feel more motivated and focused on achieving more in my next projects. And all of this is thanks to sommellerie and wine! I could never have imagined, all those years ago, that it would have enthralled me, compelled me, and captivated me as much as it has. I am so pleased to have discovered wine and all that it has allowed me to do, to be, and to enjoy.