Tilar J Mazzeo

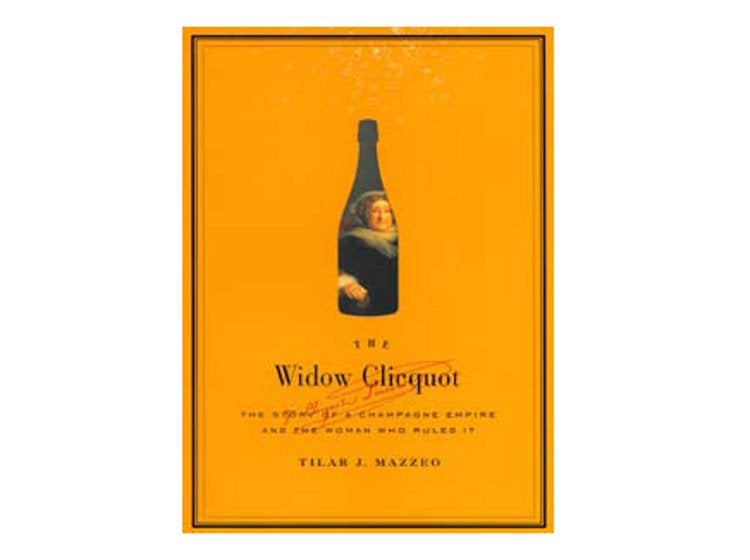

The Widow Clicquot: The Story of a Champagne Empire and the Woman Who Ruled It

Published by Harper Collins/ Collins Business £14.95/$25.95

Reviewed by Michael Edwards

This is a fine addition to the world of wine literature, an engaging biography of the diminutive woman and brilliant entrepreneur who regularly outsmarted her male rivals in the race to win new markets for her Champagnes across 19th-century Europe. Writing with the scholarly integrity of a historian, enlivened by a racy tempo that would not disgrace a novelist, Tilar Mazzeo delivers an intellectually convincing and compulsively readable narrative of the Champagne trade and France itself throughout Madame Clicquot’s eventful life of 89 years.

We see her as a teenager witnessing the French Revolution; as a young widow struggling to build a fledgling international business in the nightmarish scenario of the Napoleonic Wars; as the resilient — and lucky — entrepreneur who survived the near collapse of her bank under the post- Waterloo Bourbon monarchy, going on to become one of the richest women in France in the relatively tranquil 20-year period of prosperity of the citizen-king Louis Philippe prior to 1848; and finally as the family matriarch who had married her daughter and granddaughter into France’s most aristocratic families while creating a very modern style of management.

The early life of the grande dame is the most riveting part of her tale. Born Barbe-Nicole Ponsardin in 1777, the elder daughter of a rich wool merchant in Reims, our heroine becomes vividly alive on the page when she is sent at the age of 11 to the city’s royal convent school of St Pierre-les-Dames, there to learn the social graces of the wealthy daughters of the social elite. It should have been a haven of safety. But this was June 1789, a month before the storming of the Bastille that triggered the French Revolution. Just 90 miles (145km) from Paris, all Reims quickly took to the streets in an eruption of class warfare.

The royal abbey suddenly looked an extremely risky lodging place for privileged young girls. When he heard news of the uprising, Barbe-Nicole’s father, Nicolas Ponsardin, took a very pragmatic decision: He not only joined the revolution but became a member of the Jacobin fringe that called for the abolition of the monarchy. But as Mazzeo observes, “appearances were deceiving [… The] Ponsardin family was living an elaborate lie — or at least a carefully constructed public deception.”

Nicolas, at heart a convinced royalist, was no martyr; he saw it as his duty to protect the family’s fortune, and he grew richer during this peasant revolution. The Champenois have always known the importance of keeping their secrets. Barbe-Nicole inherited her father’s hard-headedness, but when she was betrothed at the age of 20 in an arranged marriage to François Clicquot, the son of another Reims cloth merchant who was starting to trade in Champagne wine, it soon became clear that her young husband was something of a dreamer who went out on a limb to sell wine in foreign markets that were not yet ready for them. François was prone to severe mood swings and in 1805 became very depressed at his commercial failure, finally succumbing to the typhoid that was the official cause of his death. An ugly rumor persisted that François may have committed suicide, perhaps suffering from what we now call bipolar disorder. Mazzeo does not dismiss this, lucidly outlining both possibilities.

Post-1805, the relationship between Barbe-Nicole and her great Germanborn salesman, Louis Bohne, is beautifully conveyed. Louis finally convinced the young widow of the rightness of an international sales strategy concentrating on Eastern Europe. I enjoyed reading of his disdain for the British, whom he called “maritime harpies.” He even dreamed of drowning them in the Champagne of the Widow. The great regard of the boss for her employee is shown in the gift she gave Louis before his triumphant voyage in 1814 that ended in his breaking through the Allied blockade of the Baltic ports, opening the way to the Russian market. In his hamper were 18 bottles of red Cumières wine, six bottles of Cognac, and a copy of Cervantes’s Don Quixote, the story of the romantic knight willing to fight the most hopeless of causes.

Barbe-Nicole was content to live a long widowhood of 60 years, but she was no nun, having a worldly sense of humor and a weakness for handsome young men. She adored her lusty sonin- law, the libertine Louis de Chevigné, but in the end she excluded him from any power in the house, preferring to make Edouard Werlé, the man who had hocked his assets to save her from bankruptcy, a full partner. Business is business, especially in Champagne.