Last year was a record-breaking year for the fine-wine industry all round. Prices hit new all-time highs with the Liv-ex 50 index breaking through the 400 barrier for the first time on December 29. Following initial rallies by oil and then gold in the first half of 2010, the steady growth of wine prices saw the Liv-ex 100 index end the year 40.5 percent higher than in January. The compound annual growth rate since the Liv-ex 100 began in 2001 has been a more sustainable 15 percent. Stock exchanges representing Hong Kong, the USA, and the UK, fine wine’s three major economic markets, converged in December, having risen by 14.5, 15.0, and 13.7 percent respectively during the year.

Commodities’ 2010 growth rates

Worth its weight

On the back of gravity-defying wine prices, merchants and auction houses both posted huge returns, many enjoying double- or even triple-digit growth compared to 2009. Farr Vintners of the UK achieved full-year revenues of £169 million ($260 million), more than twice those of the previous year, with almost half that amount generated in Asia and 87.2 percent from the sale of Bordeaux wines. Many of these were the much-hyped 2009 vintage, with Farr’s en primeur campaign bringing in £62.8 million ($97 million), despite not generating much interest from the USA (whose buyers represented only 3 percent of Farr’s overall sales by both value and volume. Bordeaux in all vintages is still by far the main driver of growth in the industry, with the first growths alone accounting for 60 percent of Liv-ex’s exchange turnover by value in 2010, more than ever before.

(left) and 3 (right): Farr Vintners’ 2010 sales

While Bordeaux châteaux sharply increased their release prices (by an average of more than 200 percent on 2008 for the top 22 châteaux) and merchants, too, reaped great profits, the end consumer has yet to taste the fruits of en primeur purchases, either sensorially or economically. The vintage will not be ready to drink for years to come, and prices may need as long to rally, with some form of rationalization widely considered by the industry to be both necessary and likely.

Differences (as percentages) between release prices of 2009 Bordeaux and the prices at the end of 2010

At the end of 2010, many 2009 Bordeaux wines remained below their release price, though second wines Carruades, Petit Mouton, Forts de Latour, and Pavillon Rouge have seen extraordinary price hikes. Leaving aside 2009 Bordeaux, performance has been very strong, with wine firmly on the financial radar as a truly worthwhile investment. Liv-ex pitched the benchmark investment wine, Lafite 1982, against other valuable commodities and found it to be worth eight times its weight in silver and four times its weight in black truffles, as well as being pricier than white truffles, rose essential oil, and saffron. Liv-ex stated in its December market report that “price rises of the scale we saw in 2010 are clearly unsustainable-or, taking a long-term perspective, even undesirable.”

Changing places

There’s no sign of a bursting bubble yet, as wines seemed only to appreciate in value, and auction houses have beaten 2009 revenues across the board.

Overtaking Zachys to claim the number-one spot, Acker Merrall & Condit more than doubled its revenue, falling just short of the $100 million mark. But the grand total of more than $98 million nevertheless made wine-auction history. The house brought in $28 million from New York sales, up by 55 percent on the previous year, but the real game-changer for Acker was its remarkable success in Hong Kong, where its sales grew by more than 200 percent, at $63 million from six auctions (thus averaging more than $10 million per sale, compared to Hong Kong’s average for the year of $8.4 million). Such aggressive growth is no mean feat following a highly successful 2009, where Acker was already the top player in the region, on which the house now relies for more than two thirds of its global revenues.

Auction houses’ 2010 revenue

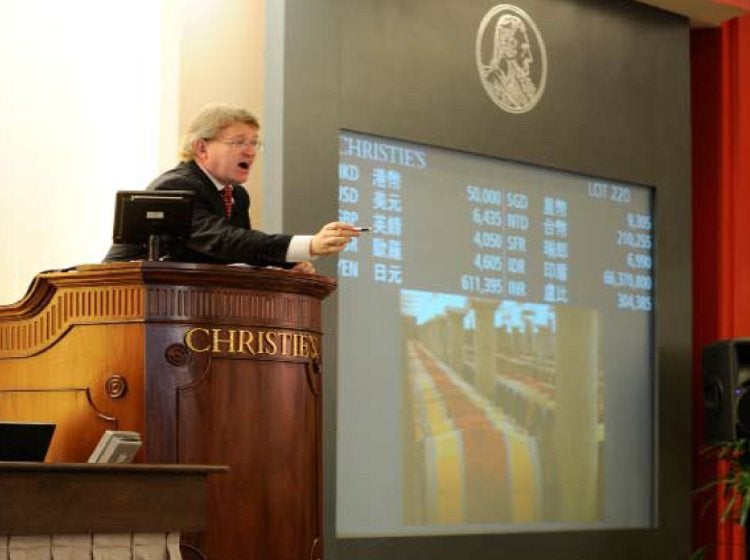

Second in line for the throne was Sotheby’s, with $88 million, just $10 million behind, or one large Hong Kong sale-the house held only five in the city. These revenues were up more than 100 percent on 2009, with 60 percent derived in Hong Kong, 24 percent in Europe, and 17 percent in the USA. Christie’s followed in third place, with a worldwide sales total of $71 million, outdoing Sotheby’s in both Europe and America but making less than half the amount of its ancient rival in Hong Kong, where its three sales accounted for only 31 percent of overall revenues.

Percentage of 2010 lots sold

The global leader of 2009, Zachys grew revenues by only 11 percent and fell to fourth position as a result. The house maintained its historically strong position in its resident United States, with $37 million in revenues second only to the wholly US-focused Hart Davis Hart. However, Zachys’ Hong Kong revenues represented only a third of its total, proving for the umpteenth time the magnitude of the Asian market. That said, Hart Davis Hart’s year-on-year revenue growth of 63 percent from seven Chicago sales is not to be sniffed at. What’s more, HDH is the only house worldwide to have maintained a nigh-on perfect average sell-through rate, passing only two lots of the 10,281 offered throughout the entire year (Fig.6, above). In sixth place, ahead of old hand Bonhams, came Spectrum Wine Auctions, founded in 2009 and specializing in simulcast auctions, which embrace the exciting new Asian market without leaving American buyers behind. This leaves only Bonhams of the truly international firms, which, despite 44 percent sales growth year on year, was down a place, deriving only 20 percent of $13.6 million global sales from Hong Kong.

Up till infinity?

In 2010, worldwide wine-auction revenues totaled more than $396 million from 132 live sales and more than $430 million including Internet sales-almost double the previous year’s total. Hong Kong categorically staked its claim as wine hub, for auctions at least, representing 41 percent of global sales by location, to New York’s 23 percent. What’s more, Hong Kong generated more revenue from 19 sales than all 47 US-based auctions, together representing 36 percent of the worldwide total (Fig.8, opposite bottom). London lagged far behind, accounting for only 9 percent, while Europe overall made up 20 percent from 61 auctions, which, needless to say, were much smaller affairs on average. Europe’s average sale total during the year was $1.3 million compared to $3 million for those held in the USA and a staggering $8 million for Oriental affairs.

A similar pattern emerged where sell-through rates are concerned, with Europe achieving a weighted average percentage of lots sold of 92 percent, the USA 96 percent, and Asia 97 percent. There’s no question Asia has once again been the driving force behind such a successful year. In a recently published IMF working paper titled “A Barrel of Oil or a Bottle of Wine: How Do Global Growth Dynamics Affect Commodity Prices?” Serhan Cevik and Tahsin Saadi Sedik found that “while advanced economies account for more than half of global crude-oil and wine consumption, emerging market economies make up the bulk of the incremental change in aggregate demand and therefore have a greater significance in determining price fluctuations.” In lay terms, Marc Fischer of Steinfels confirmed, “demand is mainly from Asia-that is, China. Should this strong demand weaken in the near future, then wine prices will fall again.”

Arguably, however, there is still enormous growth potential in the mainland’s emerging market, if Hong Kong’s progression is anything to go by. China has a population of 1.3 billion-190 times greater than the former British colony-most of which remains oblivious to wine as we know it and prefers to imbibe baiju (literally “white wine” but in fact a white spirit distilled from grain or rice, akin to turpentine in its eye-watering strength). Hong Kong’s giant sales do cater for Mandarin-speaking bidders, but Hong Kongers are still at least an equal buying presence, according to Gregory De’ Eb of local storage company Crown Wine Cellars, who estimates the Special Administrative Region (SAR) to be home to approximately 40,000 fine-wine buyers. Chinese New Year will undoubtedly have boosted trade early this year, and there’s no reason why the Year of the Rabbit won’t see steadily increasing demand from the world’s new superpower, which overtook Japan as the world’s second-biggest economy in the second quarter of 2010.

Live-auction revenues by geography

Another superpower, Château Lafite, continued to steal the limelight in 2010. One case of 2009 Lafite was sold for HK$532,400 ($68,500) at a Hong Kong auction-three times its value on the London market. Not content with the comparatively average performance of the previous vintage, the château tapped into the already tractable Chinese market by announcing a “lucky eight” symbol to feature on the bottling. Within 24 hours, the case price jumped 19 percent, according to Liv-ex. Bringing to mind Lafite’s prices, the Chinese character symbolizes infinity.

Bordeaux Index’s Hong Kong MD Doug Rumsam commented on the power of branding in the Asian market, observing, “Labels with symbols that stand out like Angélus or Beychevelle have risen to fame faster than others.” A month later, Mouton followed suit, with the announcement it has commissioned Beijing artist Xu Lei to design the original labels for 2008, immediately sparking a 15 percent rise in value on Liv-ex. The 2008 vintages of Lafite and Mouton made the biggest gains of the year, with respective price increases of 315 percent and 193 percent, and both were trading higher than their 2005 and 2009 equivalents by the end of 2010.

In October, Sotheby’s sold the most expensive bottle of wine ever to go under the hammer, for HK$1,815,000 ($234,000). The wine was 1869 Lafite, sold to an Asian private buyer in the new global auction capital, Hong Kong. It was in this SAR in May that Christie’s broke the record for the most valuable wine lot sold in Asia, with a 128-bottle, 40-magnum superlot of Château d’Yquem sold for HK$8,040,000 ($1 million) to a European private buyer. Both lots had impeccable pedigree in common, being sourced direct from the châteaux, which, as we saw last issue, can add more than 18 percent to the price of a wine bought from a merchant.

Signed, sealed, delivered

While producers’ cellars might not necessarily provide perfect storage conditions, wine benefits from staying still and being subject to only one journey. Having looked at how treacherous such journeys can be in the last Liquid Assets, minimizing the travel is a no-brainer. So much for the careful conveyance of your so-far super-provenance wine, but what next in order to maintain the chain and, furthermore, to insure it can be certified in the event of a subsequent divestment? I promised next to address the issue of storage post-voyage, the next link in the potentially cold chain that contributes to a wine’s provenance.

According to the storage guide from the well-known UK cellarers Octavian Vaults, “the deciding stage of a fine wine’s journey begins when it is laid down in storage.”

Many large-scale collectors, such as Bill Koch or Marcus D Hiles, will have their own wine cellars built, which auction houses will then visit, waxing lyrical about the pristine conditions and ideal temperatures. While wines from such collections regularly fetch premium prices, strictly speaking their consistent good storage is not guaranteed; a broken thermostat a decade ago is unlikely to get a mention by the consignor. Some premium third-party storage offerings now guarantee optimal storage conditions-for example, Octavian allocates a “Certificate of Pristine Storage” to every bottle or case leaving its underground facility.

With more and more wines being shipped to Hong Kong, to rightly particular Asian buyers, the question is as pertinent there as anywhere else. Rumsam observes, “There may not be much space in Hong Kong, but people are buying faster than anywhere else in the world. Storage companies must be fit to burst at the moment.” By De’ Eb’s calculation, the locals own around 19 percent of the world’s rare- and fine-wine collections. With 7 million residents, 18.5 percent of whom live on the island itself, Hong Kong has one of the world’s highest land-population densities, at 6,480 people per square kilometer in 2009. The city’s skyline is arguably the most impressive anywhere, built thick and high to house the bodies. That leaves below ground.

The only way is down

Aware of the fragility of the living liquid they one day hope to drink or sell at a profit, most serious wine collectors expect the best environment for their wines. Many are happy, however, to assume that their wine is stored appropriately if they are paying for professional storage, whereas industry standards can in fact vary wildly. According to De’ Eb, “most collectors are still storageignorant.”

Crown Cellars in Hong Kong offers a luxurious dining room as well as perfectly preserved and protected fine-wine storage in the island’s only underground facility

There is an important distinction to be made between a warehouse fitted with air-conditioning units and used to store wine, and a building carefully tailored to the specific needs of optimum wine storage. The former might occur where a logistics company sets aside existing space and labels it “wine storage,” whereas the latter often springs from within the wine community. However painstakingly a space is adapted for wine storage, it is widely accepted that nothing beats conditions underground.

Why? Very simply, cellars are, by nature, cool, humid, dark, less subject to vibration, and relatively secure (by dint of having fewer points of access). Banks of moist earth on all sides mean temperature and humidity do not fluctuate as extremely as outside weather patterns, forming a naturally consistent enclave that can easily be regulated.

Moreover, in the event of power failure, conditions remain acceptable for much longer without intervention than they would above ground; above ground, any serious storage facility should have backup generators to cater for this eventuality. It is for all these reasons that Hong Kong’s Crown Wine Cellars identified as its first storage facility a series of underground bunkers originally built by the British in the run-up to World War II to store weapons and ammunitions. Now a UNE SCO Asia Pacific Heritage Site, the humidified haven lies on the green side of the island, cut 60ft (18m)into Shouson Hill. The eight bunkers each have 3ft- (1m-) thick reinforced concrete walls and 40ft- (12m-) long entrances.

Despite space constraints, CWC I is in fact the only subterranean facility in Hong Kong, and “you can’t challenge” the benefits, according to Greg De’ Eb, not least because you don’t need to tamper as forcefully with existing conditions. Nonetheless, Crown added insulation and airlocks to prevent temperature exchange. There is no machinery in the facility, since this would require larger doorways, and there aren’t any windows-God forbid!

The computerized climate control is more sophisticated than conventional, unsubtle A/C, which blows ice cold or not at all (and which has become a status symbol for shops and eateries across Hong Kong, making it quite possible to catch a cold despite the blazing heat outside). Crown’s systems consist of a block divided into four quarters of air: one cold, one hot, one wet, one not. A sensor continually assesses the atmosphere within the facility, De’ Eb explains, allowing the system to bleed out the correct combination of air to maintain a temperature of 55-56°F (12.78-13.33°C), and the humidity at 65-75 percent. The dim, cool interior has vines painted on the walls, cabinets full of Riedel glasses, and a mini-library. It exudes history, as De’ Eb exudes charm, assuring me that “storage and logistics here are better than anywhere else.”

Quality control

By “here,” De’ Eb means Hong Kong, whose government is the first to introduce a quality-assurance scheme for wine-storage facilities. The Wine Storage Management Scheme is based on ISO requirements and “globally accepted practices,” with representatives visiting numerous existing western facilities including, inter alia, those of Cert Octavian and Berry Bros & Rudd in the UK, Bordeaux City Bond, and various châteaux in France and, in the States, New York’s Vintage Wine Warehouse and San Francisco’s Vinfolio.

CWC was among the first batch of nine companies to have been awarded certification in May 2010 by the Hong Kong Quality Assurance Agency (HKQAA), alongside a selection of international and local logistics companies, such as DHL Global Forwarding, as well as local wine merchant Watson’s Wine Cellar. A total of 15 certificates had been issued as at January 2011, eight in the Fine Wine category, four only for Commercial Wine, with less stringent temperature and humidity requirements, and three for both categories.

The commercial wine-storage facilities are typically ex-factories, like the seven that Supply Chain Solutions has converted for wine storage since 2008, or large warehouses. “A warehouse,” asserts De’ Eb, “should never, ever be used to store rare and fine wines, because it is not compatible with temperature and humidity control,” explaining that “the volume of air is way too large to store wine properly.”

CWC’s two additional above-ground facilities have also been included in the certification scheme, and the combined number of bottles in storage is between 600,000 and 700,000, owned by more than 3,000 private clients. Crown has had no option but to try to emulate subterranean conditions above ground, since underground space is such a rare commodity, in Hong Kong and elsewhere. CWC I, Octavian Vaults, and Horse Ridge Cellars in Connecticut, USA, are among the only existing wine-storage options below ground. All are former government bunkers, the latter “originally built to withstand an indirect hit from a nuclear warhead.” I asked De’ Eb whether an overground building can replicate the perfect wine-storage conditions of a true cellar, and he admits that “the end result can be quite close” but that you “need a lot more money to get there.”

Domaine Wine Storage is one US company trying to do just that, with its two storage facilities in St Louis, Missouri, and Chicago, Illinois, currently housing approximately 250,000 bottles of wine for 200 overwhelmingly private clients. The key considerations in adapting the two buildings included insulation, temperature, humidity, light, vibration, and audit control. Insulation is key, explains president Marc Lazar, because without it, “the greatest cooling system in the world can’t perform.” By putting a “box within a box,” you go some way toward recreating the insulating effect of the earth underground, lowering utility bills and improving temperature consistency. Any windows are blocked up and insulated, and double-door systems are especially important for large openings where a forklift might pass through, for example.

You still need cooling, but “only when you’re getting started,” because in Lazar’s experience, “thousands of cases of cold wine self-cool, and the equipment doesn’t have to work very hard.” Domaine targets 70 percent relative humidity. An automatic sensor dictates when it is necessary to use a mist humidifier to inject cold, moist air in front of fans and when, conversely, active dehumidification is required. Motion-activated fluorescent lights are used; they have lower UV than standard lighting. The sites have no major causes of vibration nearby, such as compressors, pumps, or railroad tracks, and air-conditioning systems and generators are situated outside.

Where there’s smoke…

Security is a factor much overlooked, with a tendency to focus on the atmospheric conditions. Lazar’s facilities have various security measures, including being hooked up to the local police stations and imposing restricted access out of hours, though he believes missing wine is usually down to “losing track of things, rather than fraud.” He admits having heard wine-storage horror stories and advocates the wisdom of storage separately from the retail source-“like church and state,” even if only physically separate. A merchant may often have an incentive to “borrow” the wine, potentially leaving you with a case that has different fill levels, or worse.

Domaine Wine Storage, in Chicago and St Louis, makes clients feel welcome

De’ Eb seconds this sentiment, referring to the pyramidscheme notion whereby missing cases can accumulate. He warns that collectors should physically check on their wine every five years, naming missing wine as “the biggest storage secret worldwide,” whether the result of outside criminal activity or insider jobs. He cites the bankruptcy of Mayfair Cellars in 2006, when the finance director fraudulently sold around £1 million ($1.5 million) of customers’ wines. Theoretically, a properly written storage contract should insure the ring-fencing of a client’s wine in the event of the storage company going into administration. However, it is strongly recommended that you make sure your wine is clearly labeled as such, to prevent any claim by the receiver on behalf of creditors, especially where the company is a merchant and has its own stock in the warehouse classed as a company asset.

The American model of private lockers offers much reassurance but consumes more space and is accordingly priced. (Domaine offers both options.) Small, independent cellarers are, however, on the increase. In the UK, Smith & Taylor offers cellarage in Chelsea, London, as well as designing and building private cellars for houses or restaurants worldwide. Founded in 1986 by Sebastian Riley-Smith, the storage company was one of the first not to be affiliated with a merchant, and the model has proved popular. Nexus is a more recent offering, set up in 2005 by Mark Bevan, formerly of London wine merchant Armit, in order to provide a “fully independent storage solution.” Members pay an initial £50 ($77) to have their account set up and wine moved to either Octavian or Vinothèque bonded warehouses, where they declare it “impossible for collectors’ stocks to be confused with the assets of any trading outlet.” Nexus handles the receipt of future purchases for £4.25 per case, or £2.75 from linked merchants, as well as charging rental and insurance.

Lazar’s second piece of advice for collectors is to take out an insurance policy, unless your home insurance covers wine stored off-site. De’ Eb urges all collectors to check not only that their wines are insured but that they are insured up to the current market value. In Lazar’s experience, storage companies find it notoriously difficult to secure appropriate policies covering the customer, though De’ Eb is proud to state that Crown Wine Cellars has “total and catastrophic loss cover,” which he believes to be unique in the industry. He doesn’t want to have to use it, though, since it would be impossible to renew after a huge claim. As a cautionary measure, the company closed down CWC II and CWC III because De’ Eb “felt there were intrinsic design faults” leading to insufficient security. The recent opening of CWC V has absorbed the lost capacity and offers clients the use of a “Fort Knox-style” bank vault for the safekeeping of their most precious wines.

When I followed up with De’ Eb after my visit, he asked to postpone the call by a few minutes: “Just putting a little fire out,” he explained. Needless to say, the fire was metaphorical (even the most meticulous of wine storers have to deal with the odd demanding, irate customer), and CWC did not have to fall back upon its total and catastrophic loss cover. London City Bond was not so lucky in early December, when the UK’s heavy snowfall caused the roof to fall in at its Purfleet warehouse. Management reported that more than 65 percent of the 100,000-case stock was salvaged and transferred to alternative bonded warehouses. However, because the building was unsafe to enter immediately after the accident, this operation took place over the course of three days, leaving the wine exposed to freezing temperatures in the meantime.

Most of Purfleet’s customers are small to medium businesses, such as Just Good Wine, Patriarche, and Source Wines, which were consequently unable to supply some of their customers in the run-up to Christmas. A paper written by lawyer Andrew Park and insurance broker John Haber-Smith examined the consequences of the calamity, stating that a warehouse’s terms and conditions will typically include clauses both “limiting liability in respect of the value of the goods-for example, to £100 per tonne (inclusive of duty)” and “excluding or limiting liability for consequential loss.” They add that liability is often limited to “neglect or willful damage.” Where the storage company’s insurance does not sufficiently cover the client, Park and Haber-Smith find that a wine importer’s own insurance is unlikely to cover either “stock held off their premises” or “claims arising from breach of contract,” while business interruption “will rarely be adequately covered.” Tailored policies are available at a premium.

Mining value

One storage location with built-in security is the gothically named Octavian Vaults. Located 90ft (27m) underground near Corsham, in Wiltshire, UK, Eastlays mine was first quarried in 1868 and mined for bath stone until 1934, when the Ministry of Defence acquired the site to store munitions. Before descending 158 narrow and uneven stone steps, it is obligatory to hang a clunky escape respirator around your neck, which, resembling a World War II relic and accordingly heavy, is not entirely reassuring. The sulfurous odors wafting up from below are strangely comforting, however, and the treasure trove that gradually unfolds dissolves any safety concerns that might be weighing you down.

The so-called vaults are a third of a mile (500m) end to end, a never-ending labyrinth of high-ceilinged rooms dug out of the ground, with huge pillars remaining as supports.

Cases of Lafite, Latour, and other top Bordeaux at Octavian Vaults’ secure underground wine-storage facility in a former quarry in Corsham, Wiltshire

It is surprisingly clean, well lit, and airy, thanks to (non-UV) lighting and two huge fans that replace the air from outside every 28 minutes. The temperature is a naturally chilly 55°F (13°C) and is self-leveling due to the depth, only ever varying by 1°F (0.5°C) in either direction, while the humidity remains between 72 and 78 percent and there is minimal vibration. All these factors conspire to make Octavian Vaults’ storage conditions inimitable, in the view of operations director Laurie Greer, who is not worried about the emergence of potential competitors: “If you took on a mine now, it would cost millions.” The electricity bill alone is £12,000 ($18,600) per month, and Greer says it cost Cert Octavian around £3 million ($4.6 million) and three years to convert the subterranean space into a suitable wine warehouse, including two years to control the humidity. When the mine was acquired in 1989 by entrepreneur Nigel Jagger-Cert Octavian’s Chairman- the porous sandstone had led to damp problems, including fungus, but the atmosphere is now regulated by dehumidifiers.

Greer concedes that Jagger’s acquisition of the site for the purpose of wine storage was “more luck than judgment, if I’m fully honest.” Jagger recounts his father’s sarcastic quip on learning of his acquisition of the mine: “Well, everybody in your position should have one of those.” Two decades on, Jagger reflects, “Really, you could argue you do need one if you’re trying to provide the specialist fine-wine trade with what it needs. Before, the trade was very much relying on the ultimate customers’ perceptions.” The facility, with the capacity to house 700,000 cases, is today widely recognized as the benchmark by serious wine collectors across the globe, though a handful of other, much smaller operations do exist below ground, such as CWC. “The naturally occurring conditions are a great advantage,” allows Jagger, continuing, “It’s extraordinarily difficult to provide what are the historically proven ideal conditions for fine-wine storage in a building on the surface.” Echoing De’ Eb, he concludes, “You can get fairly close, but you’re going to have to spend quite a lot of money.”

Despite a wave of Asian collectors coming around to the idea of local storage options, 30 percent of Octavian Vaults’ clients still come from the Far East, with 60 percent from the UK. Trade customers must have been in business for five years, “to prove they’re not charlatans,” in Greer’s words, before joining a club that currently includes Corney & Barrow, Private Reserves, Justerini & Brooks, Armit, and Farr Vintners (who alone have 18 dedicated warehouse staff).

Scouring the endless rows of cases, it quickly became apparent that I was not the only WFW contributor on a celebrity-spotting mission. Between us, we formulated theories about code names and pondered the meaning of some seemingly incongruous Prosecco among the racks of investment-grade tipple, though I cannot divulge any details here. Octavian insists on protecting the privacy of all clients, including the vaults’ 1,850 private customers, who include wine lovers from the worlds of sport, music, finance, and retail, with Andrew Lloyd Webber and Guy Hands among the few who can be named. Identity apart, customers seem happy to pay a premium to keep their wine at Corsham (which is pricier than Octavian’s aboveground facilities), and Farr’s director Stephen Browett goes as far as to declare it “better than any château in Bordeaux.”

Individual answers to the provenance conundrum do exist, in the form of offerings such as eProvenance (see WFW 30), Octavian Vaults, and Crown Wine Cellars, but the chain is not necessarily complete until perfect storage is grafted on to sound transportation. According to Greer, not many of the vehicles he sees coming in and out of Corsham are refrigerated, which he rationalizes in economic terms: “It comes down to pounds, shillings, and pence in the end.” Cert Octavian has had discussions with eProvenance regarding its groundbreaking temperature-tracking systems, but they have not forged a working relationship as yet. Until a user-friendly, affordable, end-to-end solution is created, the chain will inevitably continue to be breached but, everybody hopes, less and less frequently.