After business school, Patrick Bernard started out in the family company, grape brandy and eaux-de-vie producer Lucien Bernard & Co. Founded in 1928, the firm is still part of family group Financière Bernard today. “I’ve always wanted to run a business I’d want to be a client of,” he says. “Finance interests me because it’s obligatory, but it’s not my passion. My passions are wine and marketing.”

In 1983, Patrick Bernard branched out and founded fine-wine négociant business Millésima, under the umbrella of the group. The third arm of Financière Bernard began life simultaneously, with the acquisition of Pessac-Léognan cru classé Domaine de Chevalier, led by Patrick’s cousin Olivier Bernard, current president of the Union des Grands Crus de Bordeaux. Et voilà, Bordeaux royalty is born.

At first Millésima followed the usual model of the Place de Bordeaux, selling to importers worldwide, anywhere from Belgium to the USA, as well as to retailers and restaurants inside France. Four years later, in 1987, Bernard decided to break the mold and sell to private clients. “I got involved through passion, and I started with a blank slate. I didn’t have my father telling me, ‘This is how we’ve done it for generations.'” He quickly forged his own path, with no historical ties to the wine world holding him back. A year later, Millésima posted its first catalog.

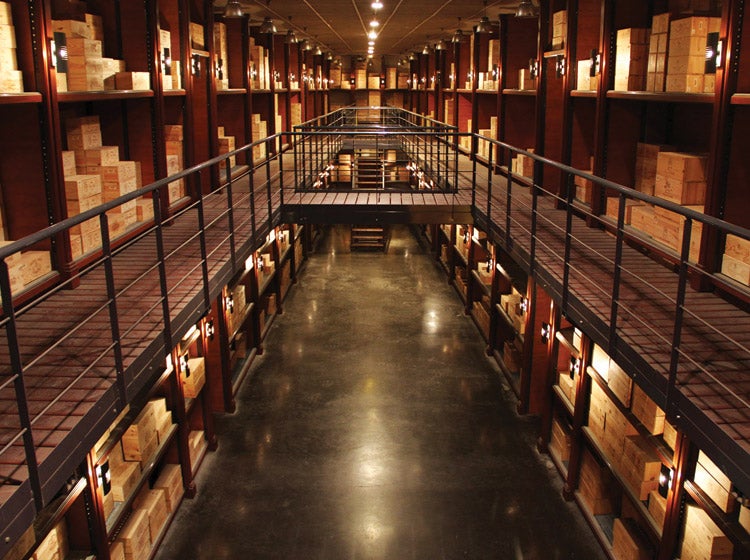

Millésima’s capacious cellars. Photography courtesy of Millésima

Millésima was not the first to sell direct to private clients, but it was the first to target this market actively, as its primary strategy. Patrick Bernard cites Duclot, Jean-Francois Moueix, Maison Cordier, Maison Descaves, and Johnston as négociants who already sold to a few individuals here and there, “but they didn’t do any marketing,” he clarifies. “I’m a hunter, and for me marketing is hunting, seeing where the game is.”

At this point, in 1988, two subsidiaries were created to carry out the different roles, ensuring Millésima would not be in direct competition with trade clients. Sobovi, 95 percent owned by Millésima, would focus on serving the domestic wine trade. Bernard et Meneret would concentrate on selling to importers. When the latter was divested in 2001 to Ballande (spawning Ballande et Meneret), a gap was left in the form of export activities, then assumed in 2006 by Sobovi, 55 percent of whose sales are now derived from exports.

The next addition to the Millésima stable was Château Peyrabon, acquired in 1998. Most recently, in 2001, Millésima embarked upon Wine and Co in partnership with LVMH, to focus purely on Internet sales by the bottle. This differentiates the joint venture from Millésima, where the average order is around ten times higher, at €1,800 including VAT. The average cost of a bottle is €57 (just over 30 bottles per order). Bernard tells me that Millésima has a turnover of around €40 million (€60 million including all its abovementioned subsidiaries). When you add the brandy business and the vineyard holdings into the mix, though, Financière Bernard enjoyed total revenues of €125 million in the year to August 2012.

Millésima, then, represents one third of the group’s revenues. Millésima’s cellars on the Quai de Paludate contained around 2.5 million bottles at the time of my visit and were due to receive 300,000 bottles of the 2011 vintage. France accounts for 45 percent of revenues, but the company is now present in 14 countries. Germany was the first addition outside France, in 1992, and remains Millésima’s second-biggest market today, representing 15 percent of revenues. The USA and Switzerland each brings in 10 percent. “We’re among the top five sellers of Bordeaux in New York,” Bernard announces proudly, through a subsidiary with a shop on Second Avenue.

Sharing the passion

The company started off more modestly, sending out paper catalogs within France. Now it has 80,000 customers. “Mail order was great,” enthuses Bernard, “because you could choose the moment to buy your wine — on the sofa on Sunday evening or at the office.” However, he thought catalogs were a bit cold. Putting himself in the customers’ shoes, he reasoned, “When you love something, you want to share your passion, to speak to someone, and it’s hard to share your passion with a catalog.”

So, Millésima set up a phone number you could call from anywhere, with someone at the other end who’d speak the right language. “In Germany, we’ve got to be German,” thought Bernard when they first opened there, so he hired a German. He has done the same for each subsequent country. Furthermore, because 98 percent of customers are men (still), “who prefer to talk to a woman on the telephone because it breaks down their inhibitions,” all his salespeople are women, he explains. The exception is in the UK, Bernard tells me, where they have a male voice at the end of the phone. “I don’t know why,” he chuckles. All the salespeople are trained tasters. He believes the key is for them to be able to “transmit a joie de vivre over the phone.”

Patrick Bernard: “my passions are wine and marketing.” Photography courtesy of Millésima.

Millésima’s sales methods have developed with the technology available to them. In France, the company was an early adopter of Minitel. “Minitel was extraordinary,” Bernard states, explaining that the ordering platform worked over the weekend so they could simply pick up the orders on a Monday morning, and it allowed them to manage administrative aspects of the business such as bank accounts. Subsequently Millésima launched in Belgium, Spain, Portugal, Austria, and Switzerland, and Bernard regretted not having Minitel in these countries. When the Internet arrived, he thought, “Ah, chic, it’s Minitel for our other markets!” So, Millésima adapted to the Internet easily, thinking of it as a “super- Minitel.” The company now has 15 websites dedicated to different countries, including Singapore, launched in January 2014.

The company employs five full-time web developers and is on the fourth version of its website in six years. In fact, the business has been “constantly growing for 15 years,” explains Bernard, investing in marketing teams, Google AdWords, and websites, all across an expanding number of markets, though more cautiously in those that are in economic crisis and more heavily in those that aren’t (“We’re investing like mad in Switzerland, but Spain’s not going so well at the moment”).

Millésima’s head count has grown from 28 to 52 in the past three years. The company has an operating profit margin of more than 10 percent. The normalized margin would be higher; I was given to believe that the margin in France — where the company is most established and investment has stabilized — is significantly higher. Selling direct to the end consumer, Millésima’s gross margin on the wine it sells is of course higher than that of traditional négociants, at around 25 percent (instead of 15 percent), but it has higher marketing and logistics costs.

Millésima’s distribution network is revolutionary in more ways than one. The négociant was not only the first to market to private clients within France; it was also the first to sell to private clients outside France. And Millésima was the first to sell anything other than Bordeaux wine. In fact, Millésima aims to derive as much as 50 percent of its sales from non-Bordeaux wine. “That’s not to say we’ll sell less Bordeaux,” Bernard is quick to clarify, saying, “We aim for 10 percent growth in Bordeaux sales every year.” Across the group, Bordeaux still represents 65 percent of Millésima’s sales. “I see it like a matrix,” explains Bernard. “We have loads of appellations and loads of countries, and we match them all up.”

An ever-expanding matrix

Despite these key differences, Bernard adds, “As I’ve always said, I am a négociant, but one who uses direct marketing techniques to sell wine” — for example, “Millésima’s relationship with the producers is just like all the other négociants,” he explains. But did this series of mini revolutions cause a stir among Bernard’s more traditional and long-standing competitors? Not as much as one might have thought, he says with regards to selling direct, because it was much more difficult to compare prices in those days, without the Internet, so people happily bought wine 20 percent above market price. “Millésima had the reputation of being more expensive than everyone else,” recalls Bernard, “so [the producers] adored us.”

But the decision to start selling in other European countries was not received with such equanimity, with Millésima perceived as a “competitor to the clients of the clients of the Bordeaux négociants,” in Bernard’s words, leading to complaints from said négociants (cue Bernard imitating a crying baby). However, Bernard insists that although Millésima’s competitors grumbled, “they were systematically cheaper than we were, so they couldn’t accuse us of breaking the market.”

But what made things even more complicated was the introduction of the Internet, because prices were quickly comparable. “Pre-Internet, if you wanted to position yourself as the leader, you had to position yourself as the most expensive,” he says. “With the Internet, you need to be at the market price.” This was problematic, because it removed the main buffer protecting Millésima from its would-be critics. “Things have calmed down now, but it’s true that at the beginning […] we had to explain to the producers why we had no choice but to [lower our prices].”

Bordeaux producers are happy with Millésima’s pricing now, Bernard tells me, while producers outside Bordeaux are actively seeking representation by the négociant. Following a trip to the Rhône Valley last year, 13 of 15 producers approached agreed to enter the Millésima stable (only Chave and Clos des Papes declining). On this basis, it seems Millésima will keep on adding wines and markets to its ever-expanding matrix.