by Stuart George

“En primeur this year was an utter distraction. I sold more shipped wine,” said Gary Boom of Bordeaux Index, one of Europe’s leading fine-wine traders. According to Boom, Bordeaux Index sold only 10 percent of what it did during 2005’s campaign. “Prices were ridiculously high,” he complained.

Boom was dismissive rather than pessimistic, but others were downhearted before the campaign even started. Jean-Francis Pécresse, wine critic for French newspaper Les Echos, lamented, “This is perhaps quite simply the end of the primeurs market. The 2006 primeurs were difficult to sell; the 2007 ones are impossible.”

Set against a backdrop of duty hikes, difficult exchange rates, and rises in food and energy costs that pushed up inflation to 4 percent in the 15-nation eurozone, the 2007 Bordeaux campaign was always going to be challenging. Even in Singapore, where the local currency remained stable against the euro (and has risen about 20 percent against the dollar and sterling), interest in 2007 was muted.

The euro/sterling/dollar exchange rate was 15 percent worse than at the same time last year. Thus a 15 percent drop in prices would mean only a price freeze for UK and US consumers, wiping out many of the discounts made ex-château. Even a drop of 17 percent would still have made 2007 overall the third-most-expensive vintage ever.

Consequently, the UK and US markets bought much less, though the perceived quality (or lack thereof) of the red wines doubtless also contributed to the indifferent response from Bordeaux’s main customer bases. “The exchange rate was just another reason for the USA not to buy,” commented Mathieu Chadronnier of négociant CVBG Dourthe-Kressman. “It would not have bought, anyway. The US ignored 2001, 2002, 2004, and 2006. The US market buys heavily in great vintages.”

“Everybody had to try hard on 2007s,” said Mark Walford of Richards Walford, a major British fine-wine importer and also a Bordeaux négociant. “We’ve bought heavily and used the vintage to reposition ourselves, and we have sold the great majority of what we bought. It’s gone okay, but the sadness of the campaign is that people were working on tiny margins. If you didn’t, then you got stuck with the wine.” Some UK merchants were allegedly selling wines at a “crazy” 4 percent margin. “Is it crazy?” asked Walford. “There are certain wines where, if you don’t keep your position, you won’t get any next year.”

Reds under the bed

Sebastian Payne MW of The Wine Society described 2007 as “an undemocratic vintage in which properties with favored sites and with lots of cash did best. Generally the wines are for pleasurable drinking and not for outside investors. In this regard 2007 may be compared with 1999 and 2004, though the styles of each year are different.” According to a survey conducted by Liv-ex, the Londonbased exchange for fine wine, most respondents likened the 2007 wines to 1999, while those with longer memories compared them to 1984 or 1985.

The general consensus was that the red wines were “attractive and approachable” and likely to make charming early drinking. The dry whites were more highly regarded- “clearly the best vintage I have tasted for these wines, really brilliant,” reckoned Chadronnier- and Sauternes had its best year since 2001. (Years ending in “7” are often auspicious for Sauternes-think of 1997, 1967, 1947, and 1937.)

Berry Bros & Rudd in London offered more than 260 wines from the 2005 vintage and 85 from 2006. For 2007, it offered only 38. The US bought “almost nothing,” according to Mau. “But the exchange rate is not the only factor. For several years now, the American market has stocked up on the top vintages, whatever the price, and has passed up the lesser ones.

That is not just due to varying rates of exchange; it is also due to the Parker effect and his influence. On the British market, one does not know how much of the wine bought is sold on to Asian markets.” Indeed, according to Berrys’ fine-wine sales director Simon Staples, the company sent 90 percent of its first growths to Hong Kong. “I doubt anyone bought as much as they did in 2005 or 2006. I certainly did not,” said Jeff Zacharia of New York wine merchants and auctioneers Zachys. “In the US, there is not a lot of interest in these wines at this point. But I think once they come in they will sell.”

With 2007s not selling in any great quantity in the USA and UK, merchants looked to emerging markets to take up the slack. The campaign was saved by the Far East-Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and so on-and the home market bought, too. It was rumored that eurozone supermarkets were buying large parcels of 2007s at discounted prices, without which the campaign would have been even worse.

“China is a big market for us now,” said Gary Boom. “We probably sell £25,000 of wine a day to China”- though most of that is bottled wine. Start-up companies in the Far East will allegedly take whatever is available, at prices their insouciant customers will pay. “We did sell a little bit in China,” admits Chadronnier. “But it will take some time before China becomes a driving force in the en primeur campaign. […] Russia is not buying en primeur in any significant volume.”

The Champagne campaign

The week beginning April 22 saw the first few châteaux release their 2007s. In Sauternes, Château d’Arche came out at its 2006 price of €16.85, while Filhot was priced at €14.80-just 3.5 percent less than in 2006. The first week of May saw Sauternes and Barsac prices 10-15 percent higher on average than for the 2006s. Given the high quality of the wines, nobody complained much, even when Rieussec rose 30 percent on last year.

Some of the dry white wines were expensive, too. Château Pape Clement blanc followed the early trend by raising its price to €117.60, perhaps encouraged by being one of the few wines to score the elusive 96-100 Parker points. Haut-Brion blanc was released at €360, more than the red. Margaux’s Pavillon Blanc came out at €84, and €100 for its second tranche.

Many châteaux waited until Parker had published his scores in early May, while others waited until after the Vinexpo Asia-Pacific trade fair at the end of May. Those waiting on Parker had an unpleasant surprise when he published his review, titled “2007 Bordeaux: Who Will Buy Them and at What Price?” in which he declared, “There is unquestionably little need to buy these wines as futures, unless dramatic price reductions occur. I don’t expect that to happen.” Boom added, “With primeurs, the price used to go up once the wine was in bottle. But with 2007, it ain’t going to happen. The price will go down, like 1997.”

Vieux Château Certan broke the trend on June 2, releasing at €60 per bottle-40 percent under its 2006 price. VCC was “one of the most sensible, but it still didn’t make it an easy sell,” said Walford. That afternoon, a London merchant offered VCC at £620/$1,240/€787 per case, which left a margin of €5 a bottle, suggesting that some merchants were indeed treating 2007 as a loss-leading opportunity to improve or maintain positions at top properties.

Other châteaux that offered reasonable discounts vis-à-vis 2006 included Ducru-Beaucaillou (down 36 percent); Ormes de Pez (down 17 percent); Pichon-Lalande (down 18 percent); and Nenin (down 30 percent). Angélus was 23 percent down on 2006 at €85 ex-château. Margaux was the first premier cru to release its 2007, on June 5, at €240, a 35 percent drop on last year’s price. The other first growths followed suit and released their first tranches at €240, which equated to about £2,500/$5,000 a case from London merchants. The 2007 Lafite was the cheapest available vintage of Lafite, with even the 2001 and 2002 more expensive, and as such justified the raison d’être of the en primeur system (at least from a consumer point of view): that the wine should be cheaper to buy than what is already available (see table, p.18).

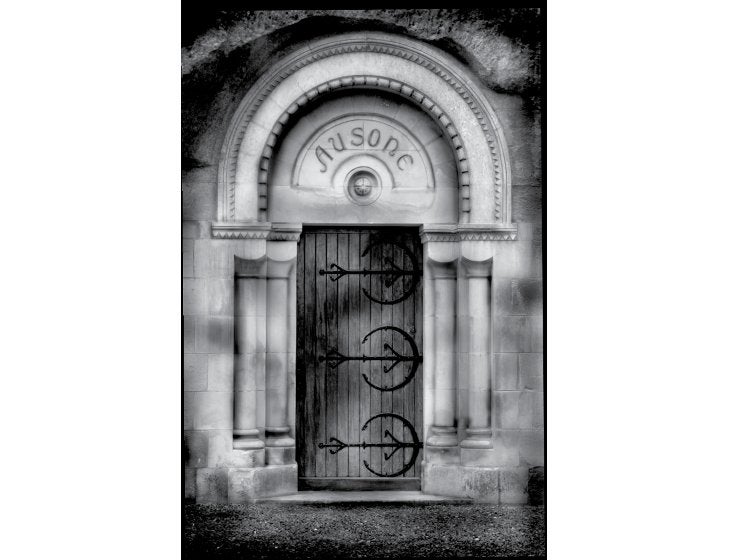

Ausone released its 2007 at €460 on June 17, down 18 percent on last year’s price. It received the highest overall scores from the leading critics and was offered with a price to match, making it de facto the best- or certainly the most expensive and praised-wine in Bordeaux today. Chapelle d’Ausone was released at €60 ex-château and was the most expensive second wine of the 2007 campaign. Of the other second wines, Carruades de Lafite doubled in price from €30 ex-château to resell at €60 ex-negociant. Demand was apparently coming from China, where people were willing to pay €180 for any bottle of Carruades. Despite not receiving a score from Parker, Carruades saw the most trade of any wine during the campaign, according to Liv-ex. It first traded on the exchange for £410 a case-£20 more than the 2005s debut price-and was soon pushed up by heavy bidding to £600. With the 1999 and 2002 both trading at more than £1,000 a case, it appeared good value compared to previous vintages. But it will be no surprise if there is a hefty rise in the release price for this wine come next year’s campaign. As Boom said, “Carruades has become a brand. You could bottle water and sell it in a Carruades bottle.”

Yquem was released on June 19 at €330, up 10 percent on the ex-château price for 2006. Cheval Blanc 2007 was released on June 18 at €370, down from €480 for the 2006, but still 54 percent more than the Médoc firsts. Cheval ’85, ’89, ’95, and ’96 were all available for less than the 2007. Boom asked, “Why would any sensible person pay £3,800 for Cheval Blanc when the same, if not better, quality can be had with the 1999 for £2,000?”

Léoville Barton came out on June 3 at €34.50, 10 percent under its 2006 price. Anthony Barton said the fact that some négociants were selling under the official resale price set by the châteaux indicated that the release prices were too high. Liv-ex reported that demand was relatively strong for Léoville Barton, with more cases being traded on the exchange than for any other wine apart from Carruades de Lafite. The price actually softened slightly, however, as the campaign proceeded, moving from £350 a case to £340, suggesting supply remained plentiful, despite it being the cheapest Léoville Barton available in the market, at £70 less than the 2002.

“When Léoville Barton struggles- with its legion of loyalists and repeat buyers-you can be sure it is a campaign to forget,” noted Liv-ex. Many châteaux, however, were not so benevolent. Gruaud-Larose (€29), Talbot (€24), and Phélan Ségur (€17.10) -the latter one of the few estates not to release its 1997 at a vaunted price, and which opted out of en primeur altogether in 1998-were all released at a reduction of less than 5 percent on 2006, which was negated by the exchange rate. Pontet-Canet came out on May 23 at the same price as last year.

Purchased from AXA Millésimes in 2006 by Syrian-born British businessman Simon Halabi, Cantenac Brown was one of the worst culprits, “whose grossly inflated price [€38] bore no relation to its quality,” said Payne. It is also perhaps not coincidental that pricing decisions for some of these châteaux are made in Paris or London rather than Bordeaux. As more groups move into Bordeaux, the pressure to buy several lesser wines in order to secure the grand vin becomes greater, too. A visit to Pichon Lalande, for instance, will also involve tasting Château de Pez and Château Haut-Beauséjour, all of which belong to Champagne Louis Roederer’s Bordeaux portfolio-though in a very civilized gesture, UK merchants were apparently given some Champagne (NV, presumably) with their orders.

Le fou du roi

Every year the campaign is criticized but the circus continues. After all, wine is made each year and has to be sold. As Payne points out, “first-growth Lafite realizes this and will have sold 95 percent of its crop, and most others will have tried to do the same. Nevertheless, classed growths and equivalents have never been richer, so it is the guys in the middle- the merchants and traders-whose margins have been most eroded and who will end up with expensive stock. The overheated market badly needs a cold shower in the form of a recession. If 2008 is unexceptional, as looks likely at this early stage, that cold shower will be turned on full blast next year.”

The continued extravagant en primeur pricing puts pressure on back vintages, which has created a market in which young vintages are overpriced and older vintages underpriced- so how will the market correct itself? “I think the older vintages will increase in price,” predicted Boom.

The Chinese market, which is just beginning to develop, will probably buy the 2008s. Not only are the color red and the number 8 lucky, the vintage is also an Olympics year. But there was a danger of mildew in Bordeaux in mid-June, and it is likely to be a very small crop, particularly for the white wines, with prices to match.

Malthus inflation (nothing to do with the price of Le Dôme 2007) is about supply constraints coming up against the rising expectations of the newly well-off. There are more players in the fine-wine trade now, and the increasing power of emerging markets means that châteaux are reluctant to drop prices too much, if at all.

Consequently, it is more difficult to establish a position with a château than it was in the 1980s or 1990s. But far-sighted merchants have maintained their position in 2007 and should reap the benefits in time. Likewise, châteaux that priced sensibly were rewarded with decent sales and good will.

2007, then, was a year to reposition: “A year in which you could take better positions with the more sought-after châteaux,” said Walford, “something that could not be done in 2005 or even 2006, though it was possible in 2004.” Négociants and merchants can only improve their positions in “weak” years, but the top châteaux know now that even in these vintages somebody, somewhere, will buy the wine.