The first half of 2011 was a relatively calm period for fine-wine prices. The Liv-ex 100 Index rose by a respectable 5.5 percent, compared to 24 percent during the same period in 2010. March, April, and May of this year were stagnant, with oil, gold, and the Dow Jones stealing the limelight. Then June’s en primeur activity gave the Liv-ex 100 a small boost, allowing it to end the period just above the Dow Jones and above crude oil, which lulled after a dramatic rise during the Arab spring.

The Liv-ex 500 Index, on the other hand, rose steadily and convincingly throughout the first six months of 2011, almost matching the 12.5 percent rise of gold. This suggests the second echelon of wines fared significantly better than the top 100: perhaps the meteoric rise of the first growths and their second wines is finally proving unsustainable as prices force buyers to expand their horizons just a little. The gap between the top 100 and the next 400 that has been widening for the past two years may well be beginning to shrink.

Heavyweight Hong Kong

Auction houses have commented on the increasingly eclectic taste in Asia. John Kapon, CEO of Acker Merrall & Condit, observed, “While Bordeaux will always be king in the Asian market, it is clear that Chinese collectors have crowned Burgundy as their queen.” Nonetheless, be it for first-growth claret or rarefied Burgundy, the quest for luxury is still going strong in the Far East. On June 25, Spectrum Wine Auctions occupied Hong Kong’s new 118-story International Commerce Centre (ICC), boasting Rolls- Royces and Ferraris at the entrance. Spectrum “matched the splendor of the space” by serving three mature first-growth vintages plus Ausone and DRC La Tâche. The auction house recognized a new trend, announcing, “Château Mouton Rothschild shows as the new Asian darling.”

Wine v stocks and commodities (2011)

Spectrum is the only auction house to have held its wine sales solely in Hong Kong so far this year, although 30 percent of lots in its June 25 sale were sold to non-Asian bidders online and by phone. The top four auction houses in the first six months of 2011-Sotheby’s, Acker Merrall & Condit, Christie’s, and Zachys-have each hosted three auctions in Hong Kong. Acker is still most heavily weighted toward Hong Kong, generating over two thirds of its wine-auction revenues in the Asian capital, as in 2010. Sotheby’s Hong Kong sale proportion is 60 percent, while Christie’s and Zachys rely on Hong Kong auctions for 55 and 56 percent of sales respectively.

Turnover derived from the Far East eclipsed that from other regions to July, for the first time representing more than half of the global total, at $131 million. The USA represented 31 percent and Europe only 16 percent. Conversely, Europe had the highest number of sales at 27, while the US held 26 and Asia 16. Auctions held in Hong Kong raked in more than two and a half times the average revenue per sale of auctions in the US and more than five times that of those held in Europe, proving that while Asian buyers’ horizons get broader, their pockets remain as deep as ever.

Wine-auction revenues by continent, H1 2011

Asia’s turnover to June represents a 93 percent increase on the same period in 2010, seemingly defying any notions of a slowdown in the fine-wine market. European and US sales also increased significantly over the period, by 63 percent and 29 percent respectively. This led to a very healthy worldwide total of $262 million, up 60 percent from the first half of 2010. The actual number of sales held globally only rose by 18 percent, and the number of total lots by 20 percent. Each lot was worth a staggering $4,422 on average -33 percent more than in the first six months of 2010.

Acquire and conquer

Acker Merrall & Condit hit the $50-million mark worldwide by June, up from $47 million in the same period last year. Determined to continue its expansion, Acker acquired Edward Roberts International on June 21 for an undisclosed sum. As things stand, these additional wine-auction revenues will be nothing more than a drop in the ocean; the Chicago-based auction house made $2 million from eight sales in the past year and a half prior to its acquisition. However, it is unlikely that Acker will settle for an average auction revenue of $250,000, when its own historic average is closer to $5 million.

Hart Davis Hart currently dominates the scene in Chicago, the second-largest US wine market after New York. In the first half of 2011, the city achieved wine-auction revenues of almost $26 million from six sales, ahead of London, now down in fourth place with $24 million from more than twice the number of auctions. These results are almost exclusively thanks to Hart Davis Hart, which has an unparalleled average sell-through rate of 99.9 percent.

The house now looks set to have a battle on its hands. Kapon referred to the acquisition as a demonstration of the company’s “commitment to the US market and our determination to maintain and build on our worldwide leadership position.” It’s fighting talk. However, Acker slipped back into second place in the first half of 2011, despite having ended 2010 at the top of the pile. Sotheby’s pipped Acker to the post, with $53 million to June. Third and fourth on the global leader board, Christie’s and Zachys are neck and neck, with turnovers of $47 million and $45 million respectively.

Who’s rare wins

In June, Christie’s recovered decisively from its earlier Hong Kong wobble, holding a white-glove sale of ex-Château Latour stock. The house had suffered unprecedentedly poor sell-through rates in the city in March (89 percent) and again in April (69 percent) and, despite its late comeback, still finished the half-year with a weighted-average sell-through rate 10 percentage points below its peers’.

Charles Curtis MW, head of wine at Christie’s Asia, put the difference in performance down to the rarity factor of the exchâteau stock, suggesting that buyers are increasingly on the lookout for wine with a proven history. This is recognized by Jason Boland, Spectrum Wine Auctions president, who said the top-performing lots at Spectrum’s June sale “were driven by provenance and condition, and buyers proved willing to pay a premium for wines coming from the auction’s three extraordinary single-owner collections.”

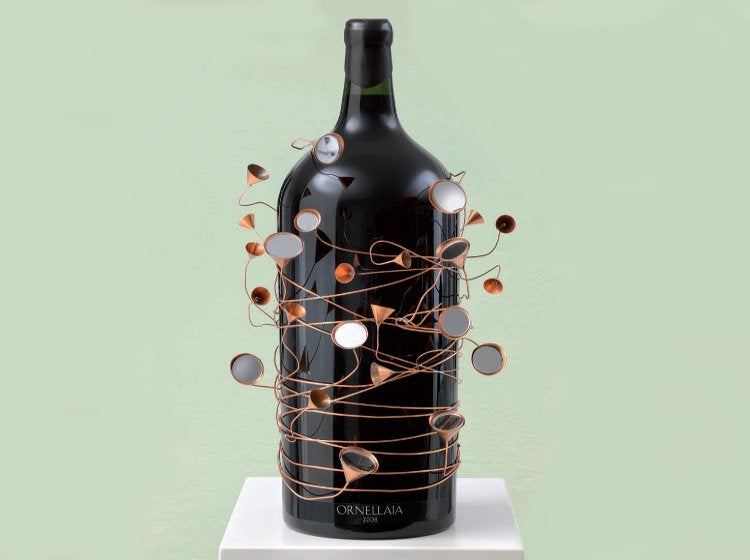

An out-of-the-ordinary offering also attracted bidders to an auction with a twist, held in Berlin on May 19. Ornellaia’s Vendemmia d’Artista charity auction featured a selection of large-format bottles with original artwork by German artist Rebecca Horn. This year’s theme was Energia, referring to the force and dynamism of the vintage. The auction took place during a gala dinner in the capital’s striking Neue Nationalgalerie. Full-height glass walls on four sides created a 360-degree panorama of raindrops capturing the evening sunlight, falling as the bubbles in our glasses rose. The reflected light bounced energetically off the copper-adorned bottles up for sale later on, perfectly expressing Ornellaia’s theme.

The bidding took a while to get going, and Christiane zu Rantzau, chairman of Christie’s Germany, was not getting much back from the floor to begin with. “Any charity is a challenge,” she had cautioned beforehand. Bolstered by only a tiny handful of active bidders among the sea of tables, all nine lots eventually sold satisfactorily, after unabashed perseverance by zu Rantzau. The unique combination of wine and art attracted new buyers to the scene (see buyer interview). For Georg Kofler and his wife, buyers of the final lot-the Salmanazar-this was their third wine auction. “Tonight we are more art buyers than wine buyers,” Kofler said. The 9-liter bottle fetched 30 times the going rate of the Ornellaia 2008 it contained.

New kids on the block

Zu Rantzau remarked that, in her experience at Christie’s, customers collect both wine and art. “We’re trying very much to combine different categories,” she told me. “We like the cross-marketing effect,” she went on, adding “art buyers increasingly buy wine.”

In the USA, the cross-category model is being developed, with established auction houses making the horizontal move into wine. Breaking off from the Spectrum Group, arms and armor specialist Greg Martin Auctions returned to private ownership earlier this year. Martin Wine Auctions’ first sale was held in June in collaboration with Heritage Auctions.

Only two months before, in April, Heritage, better known for auctioning collectibles such as coins and comics, held its inaugural wine sale. The house has introduced the practice of publishing reserve prices in its catalogs and revealing absentee bid levels during the auction. “We are finding the transparency of our operation is really resonating with buyers who have a lot more control over their spending and are therefore winning a higher percentage of their carefully placed bids, which can only be a sign of changing times,” said Frank Martell, Heritage’s director of Rare & Fine Wines.

Funds for thought

Auction houses are not the only ones to recognize an opportunity in fine wine. In WFW 32, I discussed the advent of wine funds a decade ago and how the industry has progressed since. Having examined funds’ performance and risk profile, I promised to delve deeper into how they are structured and treated for tax, as well as telling the cautionary tale of some failed funds. Here, I examine the tax implications of investing in wine-in particular, a new wine fund set up this summer to marry wine’s returns with the maximum potential tax breaks.

While wine is a high-performing asset and a valuable diversification tool, in most relevant jurisdictions it is not classed as an investment, and thus wine funds themselves cannot be regulated. All wine funds are set up in two distinct entities: One company owns the assets in which the investors have a share, while another acts as the fund’s manager, receiving the fees. The latter, in the UK, is generally an FSAregulated body, providing some level of assurance to investors, as is the case for OWC Asset Management (Vintage Wine Fund [VWF]’s general partner) and WAM (Wine Asset Managers). While the UK’s Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 doesn’t cover wine as an investment, the FSA is interested in regulating the marketing-not the managing-of wine funds. The funds can only target HNWIs (high net-worth individuals) or “sophisticated investors”-people deemed wealthy or financially able enough to risk their money investing in unlisted securities.

Taxing issues

The fund “wrapper” depends on a number of considerations, such as who the targeted investors are and what the tax treatment will be. Perhaps one of the reasons for the UK’s position as wine-fund hub is the country’s classification of wine as a wasting asset, with a life of less than 50 years, meaning capital gains tax (CGT) is not payable on any gains. This waiver only applies where the ultimate investor actually owns the wine-and of course only to UK investors. To take advantage of this, The Wine Investment Fund (TWIF) and the Fine Wine Fund (FWF), for private investors, are a limited partnership and an association of members respectively. Both setups mean that the co-investors legally own a pro rata share of the wine purchased by the fund manager.

Consequently, partners in TWIF, a closed-end vehicle, are unable to redeem their investment during the five-year term of each tranche, since this “would be treated as a taxable event for every partner.” The wasting-asset rule only applies so long as the acquisition and sale of wine is not classed as trading. Andrew della Casa of fund manager Anpero Capital is keen to point out that this tax break is an added benefit, and it’s the fundamentals of the asset class that are key to the investment strategy. “You shouldn’t let the fiscal tail wag the investment dog,” he opines.

WAM’s UK vehicle is open-ended, and while it has a buyto- hold strategy, members are able to make redemptions every quarter with 60 days’ notice. Unfortunately, wine is not immune to inheritance tax. In August 2010, HM Revenue & Customs clarified that, contrary to “information in the public domain” implying “that for inheritance-tax purposes wine cellars are valued at the purchase price,” in fact “a wine cellar must be valued at its open-market value.”

Both Anpero and WAM also have funds designed for institutional investors, in the form of Unregulated Collective Investment Schemes (UCIS). Like many others, these are domiciled in offshore tax havens-in this case, Bermuda and the Cayman Islands. In January, TWIF announced plans for a third incarnation: an AIM-listed company. However, no progress had been made at the time of going to print.

Enterprising scheme?

London-based Ingenious Group has added a new tax break to the list of those offered by wine funds, launching an Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) for wine, called Vindemia. This structure provides UK investors income-tax relief on any gains. Ingenious Investments, the group’s largest division, has previously focused on media, leisure, and clean energy. “We’re really all about alternative investments,” says Ingenious director Dylan Jones. Recognizing an appetite for wine as an asset class among its existing investor base, Ingenious thought about how it could turn that into an investment offering.

“EIS is an incredibly popular tool, not least since income tax was raised in the last budget,” says Jones. “And funds in the past have been without tax structuring.” The primary benefit of an EIS is that it enhances returns by 30 percent by offsetting the investment against UK income tax. In other words, if you invest £10,000-Vindemia’s minimum investment-in an EIS, the income-tax relief means the net cost of your investment is £7,000. Furthermore, the EIS structure can also mitigate the downside through loss relief: If the cash return is less than £7,000, and you’re in the 50 percent tax bracket, you can offset 50 percent of the loss, meaning the most you could lose is £3,500.

I asked Peter Lunzer, adviser to Vindemia, why this hasn’t been done before in the wine world. “As wine individuals, we would be sent a pack by the government,” he explained, concluding that faced with the bureaucracy, “I think we’d decide to do something else.” Essentially, setting up an EIS is a complicated process, requiring “a team of highly qualified individuals.” Ingenious offered the relevant experience, as well as “direct access to an investor base that already knows the product,” added Jones.

Jones talks about EIS having had “huge coverage since the last budget,” when the income-tax relief was raised from 20 percent to 30 percent. It was this significant shift that caused the delays to Vindemia’s closing, initially scheduled for March 15 but extended twice to July 29. “We wanted to be able to offer the increased tax relief to investors,” explains Jones, “so we had to extend into the new tax year.” The second postponement was in order to give investors more time to make a decision, Jones adds, and not, as some competitors had guessed, because the fund was “sticking.” Having aimed to raise more than £5 million ($8.2 million), Ingenious eventually secured £5.9 million ($9.7 million) by the time the fundraising period closed.

An EIS, apart from offering the tax breaks outlined above, is also exempt from capital-gains tax, which is fortunate, since wine would not qualify as a wasting asset in this structure, which must trade its assets (and would normally trigger CGT on a wine investment). An EIS is, thus, distinct from other investment funds in that it must be a trading operation and therefore cannot adopt a buy-and-hold strategy. Instead, Vindemia will consist of a series of trading companies with ordinary wholesale and retail operations. (Each can hold up to 20 percent of assets that aren’t traded, and Vindemia will take advantage of this to include an element of more traditional Bordeaux investment in its offering.)

Each company will have a different strategy-for example, one will concentrate solely on Bordeaux, while another might have a Burgundy slant (but trade in Bordeaux, too). “The trading operation is based on the idea of iconic wine labels recognized globally,” asserts Lunzer. He cites Brunello from Biondi-Santi as an example of a wine that would be “recognized by the buyer, who would buy it whenever he saw it.” Vindemia’s strategy will involve purchasing wine from sources such as auction, private individuals, and Liv-ex and selling “as close as we can get to the end user.” Lunzer speaks enthusiastically of wine consumers “on their yachts or in their chalets” who’ll pay over the odds for a particular wine there and then.

Each company will have “fully diversified trading strategies,” states Jones, with multiple exit options-from selling to merchants through listings on Liv-ex and Winesearcher.com, to offering consignment stock in highend hotels and restaurants. “Wealthy restaurants would love to increase their window dressing without financing it,” enthuses Lunzer. The concept of consigning stock to the hotel and retail industry would involve using fridges-Eurocave, for example-to display stock such as Rhône and California wines-“things we don’t need a team of salespeople to sell.”

When I queried the amount of work involved in this strategy compared to a traditional buy-and-hold fund, Lunzer acknowledged, “This is probably five times over the top in terms of effort.” The question for any investor must be whether the returns will justify the fiscal tail.

Going under

So, fiscal benefits aside, should you invest in a wine fund if you have some spare cash? It’s undeniable that some wine funds have made tempting returns in recent years. Nonetheless, most funds advise that wine should only make up a small proportion of an overall investment strategy, given its wonderful qualities as a diversifier. Choose carefully, however: Wine funds are not a guaranteed panacea to economic quandaries. While wine has proved it can outperform bull and bear markets, it was not totally immune to the 2008 crash. Between July 2008 and July 2009, TWIF and FWF lost about 18 percent and 20 percent of their net asset value respectively, similar quanta to stock indices such as the S&P 500.

For the wine funds that have met with success, there are almost as many again that have met with obstacles leading to their demise or even preventing them from launching. Ascot-the first wine fund-made what Lunzer calls “the not-unusual mistake of assuming that if you have funds to invest, you should invest them immediately,” leading to poor portfolio selection.

At the turn of the new millennium, Geneva-based Ascot Wine Management set up a Caymans mutual fund, AWM Fine Wine Fund, to invest in Bordeaux, Burgundy, and “world crus.” The last category included the likes of “mid-range Rhône,” according to Andrew Davison of VWF, who adds that the fund manager “didn’t get it quite right.” Lunzer recalls a “very big portfolio of Burgundy of dubious content,” which other sources suggest included 1,500 bottles of Marc Colin’s St Aubin-a decent wine but hardly of investment class.

Others have suffered from lax pricing practices-for example, Vinum, whose portfolio was mispriced for around two years, “probably due to incompetence not malpractice,” asserts della Casa. This wasn’t picked up in time, and the fund was forced to wind up. “This creates a certain amount of concern,” rues della Casa, “and damages the reputation of the whole scene.” Sadly, some incidents are fraud-related, such as Templar Vintner’s use of Vinum material, with their own name superimposed, to front an empty shell. The company was given a warning by the Guernsey Financial Services Commission in January 2010 for claiming it was authorized by the latter to run a wine fund.

Another fund, Arch, was closed down by the Channel Islands Stock Exchange due to an issue with “general reporting standards” rather than problems with the wine pricing itself, says Lunzer. The wine fund only represented about 5 percent of Arch Global and was “an unfortunate casualty,” he continues. In fact, the fund was not actually losing money, Lunzer has since discovered, having been commissioned to sell the fund’s assets several years on. He is positive about prospects for returns to the wine fund’s investors.

Some funds don’t even make it off the ground. A tenyear capital growth fund, Red2Gold, was announced in early 2009. The fund aimed to raise £100 million ($160 million) to invest mainly in Bordeaux blue-chip wines but hasn’t yet appeared. Lunzer thinks this is perhaps due to “very high fundraising targets at a time when the market was too skeptical for something that new,” though he wouldn’t be surprised if it makes a comeback.

Comeback kid

Another comeback of sorts is the First Growth Wine Fund (FGWF), the new fund planned by Gary Boom of Bordeaux Index. Boom says FGWF will be “exactly like the Vintage Wine Fund,” in which he owned a 50 percent stake before being bought out by Davison a few years ago. Like VWF, FGWF will be an open-ended fund domiciled in the Cayman Islands, investing “pretty much in Bordeaux-the wines on the live trade screen,” says Boom, referring to Bordeaux Index’s online trading platform.

FGWF will be managed by Calico Asset Management (CAM), which will be a wholly owned subsidiary of Bordeaux Index. The fund’s managers will be Bordeaux Index’s current investment duo Joe Marchant and Geraint Carter. Lunzer questioned the independence of FGWF, asking at what price wine will be transferred from Bordeaux Index to the fund and whether it will be transparent, adding that, after all, “wine is an unregulated industry.” CAM’s managing director Marchant explained that, as well as advising FGWF, CAM will also provide some investment infrastructure to Bordeaux Index, such as systems and analysis, but that “in terms of management function, it’s a separate entity with only Geraint and myself having control of investment policy.”

While Boom initially hoped to launch FGWF in July 2011, the documentation took longer than planned, and fundraising also proved complicated: A single Far East institutional investor declared interest at £100 million ($160 million) but “didn’t want any other investors in it,” explained Boom, who was willing to hold out for the potential investor’s decision before committing to a bout of fundraising elsewhere. The fund is now set to launch in October 2011, inviting minimum investments of £75,000 ($120,000) and accepting quarterly redemptions (with 60 days’ notice). The simple fee structure is comprised of a 2 percent management fee and a 20 percent performance fee, in line with the industry norm.

Wine-fund fees are not always so straightforward, with the Fine Wine Geared Growth Fund (FWGGF) almost coming a cropper due to its elaborate fee structure. Della Casa of Anpero-adviser to FWGGF, as well as TWIF, Accilent in Canada, and SK Networks’ fund in Korea- admits that the fund’s promoter had introduced particularly high fees. The fund is 100 percent geared, making it riskier than the average wine fund, and was launched in March 2008, after which it fell 45 percent in the first year. 2011 has seen the fund finally claw its way into the black, as well as the rationalization of its fee structure. Della Casa explains that various complex fees, including promotion fees and distributor fees, have been streamlined, leaving a 0.6 percent “principal manager’s fee” and a 1.5 percent “wine advisory fee” (on top of the usual performance component).

Final thought

In a follow-up to this series on wine funds, I will investigate the role of passion in wine investment, paying particular attention to three funds: The Fine Wine Appreciation Fund, The Bottled Asset Fund, and Nobles Crus. How are different strategies affected by passion for wine as opposed to rigorous financial models? Why do some funds invest in Italian wines while others steer well clear? I will look at the internal machinations of the funds-for example, how they identify appropriate assets, where they buy and sell, and how they insure a suitable margin. Finally, I will discuss the pros and cons of DIY wine investment as opposed to funds, investigating alternative modes of investing in wine, such as managed accounts. Which is right for you, and will your love of wine cloud your judgment?