Andrew P Haley

Turning the Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class, 1880-1920

University of North Carolina Press

$39.95 / £34.95

Robert Appelbaum

Dining Out: In Search of the Restaurant Experience

Published by Reaktion Books $35 / £19.95

Reviewed by Stuart Walton

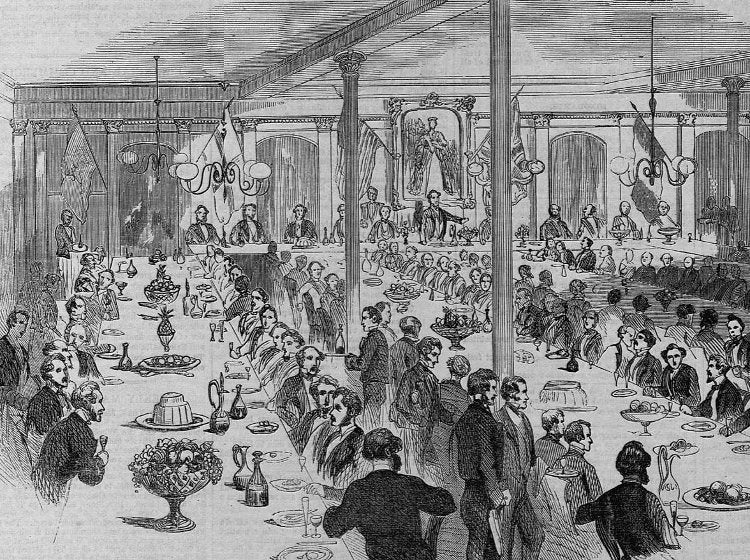

There have been few more finely, agonizingly calibrated markers of social distinction in modern social history than public dining. From the great age of the grand restaurant in the late 19th century, virtually up to the present day, when the insistence on correct dress persists unvanquished in a final few outposts of French gastronomy outside France, restaurants have been places where the elite reaffirmed their economic power and their hegemony in matters of cultural arbitration, and where the less well-off but aspirant middling classes hoped to rise above prosaic reality for at least the duration of a wedding anniversary.

A society is scarcely more publicly articulate about itself and conscious of its own distinctiveness than when it eats out, which is why the study of old menu cards has come to constitute an absorbing byway for a certain branch of sociological history. Dining in public has so often been as much about telling ourselves who we are by proclaiming our familiarity with international culinary modes, and the adventurousness of our appetites, as it is about the actual enjoyment of food.

Andrew Haley has written a valuable, deeply perspicuous analysis of the emergence of public eating in the USA , from its imbrication with a French version of luxurious living in the latter part of the 19th century, into the middle-classing and cosmopolitanizing of restaurant culture in a process that was all but complete by the dawn of the Jazz Age.

The diner-out of the 1880s entered a place where he was seated according to his perceived social standing, presented with an enormous menu of, often, hundreds of dishes written in a transatlantic French, and encouraged to tip generously in order both to insure attentive service and to establish his own membership of an affluent elite. Women were refused admittance if unaccompanied by men, asked not to smoke in mixed company, and often fed smaller portions than their male chaperones were. At the pinnacle of Lucullan discrimination was Delmonico’s, the Manhattan restaurant founded in the 1820s, which extended a century-long sway over fine dining in the city that was acknowledged to be America’s culinary capital.

All there was between this level of opulence and eating at home were lunch counters, businessmen’s eating rooms, and street stalls. Even the restaurants in the department stores that were springing up at the outset of the last century aspired to some version of elite dining, with their macaroni au gratin au Parmesan and so forth.

A rising urban middle class led by businessmen who needed somewhere to eat lunch, townhouse lodgers tired of eating in, and women shoppers with no time for return home to eat were the advance guard of a democratization in public catering that Haley traces in meticulous detail.

Out went the French menu, the nine-course dinners, and the beady scrutiny of your attire by the maître d’ in favor of an expansive appropriation of many different cuisines, an egalitarianism of tone, and even — by short-lived legislation in a few states — the abandonment of tipping, a pernicious indicator of economic status if ever there was one. The only catch, much worried over in print then and more or less since, was that a distinctively American national cuisine didn’t emerge to assume the hegemonic status wrested from French gastronomy. For this reason, some clung to the tarnished ideals of their forebears. “What is there to hope for,” wondered Charles Rosebault in The New York Times in 1921, “from a people who demand jazz with dinner?”

The answer, perhaps, had lain buried in an article in the same paper from the 1870s, in which the writer explained the typical dishes of German cuisine for the uninitiated. One of the items was “simply a beefsteak redeemed from its original toughness by being mashed into mince-meat and then formed into a conglomerated mass” – and destined, it might have added, to be the foundation stone of anything that might claim to be a national cuisine in the coming century.

Eating the culture

Only one Western culture had as little title to a national cuisine as the USA , of course, and the two isolingual nations have derived much innocent fun from reminding each other of the fact over a century and more. Robert Appelbaum’s book opens promisingly as a cultural inquiry into what we expect restaurants to do when we describe them as great, and how the restaurant scene might be expressive, even now, of the structural production of inequality in global capitalism. Is elite eating truly a part of culture? Is it possible to be a consumer without succumbing to consumerism?

These fruitful lines of inquiry, together with critical disquisitions on writing about restaurants in Sartre, William Morris, and others, struggle to be heard, however, amid a tide of anecdotalism. The author’s thintempered peregrinations around London shore up a raft of cultural clichés about British eating in a curious exercise in thorough-going self-defeat. He bemoans the existence of middlebrow chains and then eats in a succession of them. Forsaking one of Soho’s best Chinese restaurants, he hauls his wife to somewhere depressing in Chinatown, where they eat a basic set menu, which he can then roundly condemn. Why this is thought to be enlightening isn’t clear.

The book is a missed opportunity but does at least contain a succinct working definition of the restaurant as “a system for making objects of nature into products of culture.” That went very nicely with my bowl of noodles.