What’s the best way to describe a wine? Do other tasters perceive it in the same way you do? Why do some people like one wine rather than another? To me those questions are at the heart of wine rating and tasting notes, so I was fascinated by the Grand Seminar, “Pinot Noir and the Doors of Perception” at this year’s International Pinot Noir Celebration in McMinnville, Oregon, in July. Moderator Jamie Goode spoke with seven panelists, from a Harvard professor to wine writers to sommeliers, to answer them. They came out one by one, like guests on a late night talk show, for “conversations”.

The problem in describing taste, said Professor Jordi Ballesterof the Université de Bourgogne in Dijon, is that “People are different physiologically, they have different brains and cultures. We’re all living in our own taste worlds.”

Language is the way we bridge that gap; it’s the window into someone else’s experience. But times change and language evolves. Steven Shapin, a professor of the history of science at Harvard University, pointed out that the winespeak we use now is a very recent phenomenon. It arose partly from science and the chemistry of identifying flavor components and aromas, and partly from the need for more precise descriptions because of the flood of new types of wines in the market that people had never tasted before.

Two of the panelists had very different views on what that language should be. Call them the analytic and the holistic.

Josh Raynolds, who tastes and rates 7,000 wines a year for Stephen Tanzer’s International Wine Cellar newsletter, favors the former approach. “I can’t get too flowery or literary,” he said. He sticks to specific tastes and smells, devoid of obscure references and personal memories. His aim is reductive, to make notes as accurate, thorough, and understandable as possible in objective terms to give some idea of what the wine will deliver, to help people make decisions about what to buy. He thinks of what he does as a kind of basic guidebook.

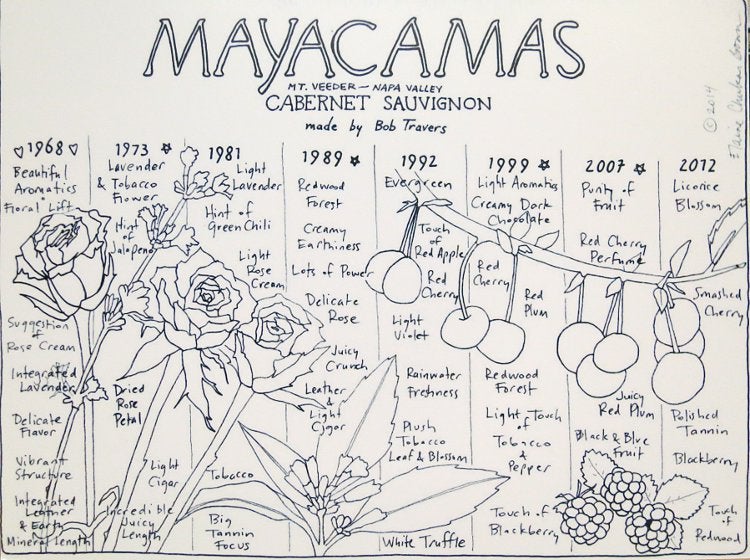

Elaine Brown, who blogs at Hawk Wakawaka Wine Reviews, has a bigger, more poetic picture in mind. “I get visual imagery when I’m tasting,” she said. Her first response to a wine is all about its color, its energy. Pictures of flowers float up. She sees its character as though it were a person and incorporates all those images into tasting note drawings, which also include words like “smashed cherry” and “juicy crunch”. They seem like visual wine haikus. “I hand draw, so they are imperfect, which gives a feeling of intimacy,” she said later, after I’d had a chance to study her vivid, intricate drawing of a vertical tasting of Mayacamas Cabernets.

But does either style of tasting note communicate the character of a wine to most drinkers? I’m reminded of the experiment Rhône Valley winemaker Michel Chapoutier used to perform with a group of tasters. He’d pour a series of wines blind, then hand out slips of paper with various critics’ tasting notes of the same wines minus the name of the critic and the name on the label. The aim was to match the tasting note to the wine it described. Very, very few people could do it.