by Roy Richards

In Act 1 of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Malcolm reports back to Duncan on the death of the traitor, Cawdor: “nothing in his life became him like the leaving of it.”

In a very different context, I thought of these words at Bill’s magnificent funeral in the timeless beauty of Wells Cathedral. It was a celebration of all that was most wonderful in the Anglican tradition: the choral music, the readings, the much-loved psalms and hymns, culminating in the stentorian Old 100th:

“O enter then his gates with praise; Approach with joy his courts unto.” All that was lacking really was a gun carriage, but that’s a small detail.

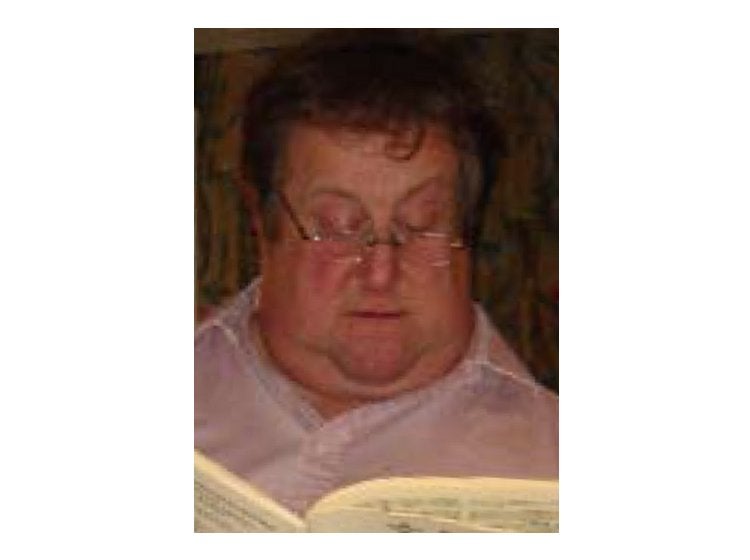

As Bill’s coffin passed by my pew, I fancied I heard him say, “What’s that tosser doing here?” – Bill’s sotto voce was another man’s declamation. I don’t know whether this remark was addressed to me or to some other hapless member of the wine trade, but I should perhaps explain that “tosser” was his preferred abusive term of affection, or affectionate term of abuse, depending on how one sees these things. And there were an awful lot of tossers present. As the tears flowed down my cheeks, and later when I reread his many obituaries, I thought how this man – generous of girth, generous in his kitchen, generous with his wine cellar, with his withering contempt for the mean-spirited – had become a national treasure. I realized that the huge congregation, gathered there to pay their last respects, all knew him differently, all believed they had a claim to a different part of his generosity, or indeed of his contempt.

I did not know Bill until I had my first restaurant and he his first wine business. Our paths, surprisingly, had not crossed at Cambridge; I was a year or two older. I imagine, however, that his school days passed like mine in a gray, austere Britain, marked by relentless decline and loss of empire. Born in 1954 – at least, and appropriately, after rationing ended – Bill would have lived through Suez in 1956, Macmillan’s “Wind of Change” speech in 1960, the grim years of Wilson’s socialism starting in 1964, and in 1965 the funeral – where there was a gun carriage – of Winston Churchill. In the midst of the gloom of sensory deprivation, in 1960, Elizabeth David published her French Provincial Cooking, allowing a few rays of Gallic sun to illuminate the possibility of another, more sensual life, complete with food and wine. It was the stuff of dreams. As a plump boy at his boarding school, Bill would have been teased mercilessly and would have had ample time to build his defense mechanisms and Rabelaisian persona – perhaps less the Gargantuan caricature of his obituaries, and more the subversive wisdom in folly of Rabelais’s Tiers Livre, where laughter represents victory over authoritarian fear, and truth lies in la dive bouteille.

With his close-set hunter’s eyes, sparkling with a quick intelligence and inappropriate ideas, Bill was nobody’s fool, nobody’s Billy Bunter. Cultivated and extremely well read, he had a hatred of hypocrisy, while well understanding its subtle ways. A founder, and irreplaceable, member of my dining club, Les Branleurs, he presided with great authority over our soirees dedicated to the irreverent appreciation of great, mature wine, generally claret.

In wine, he knew what he liked, and more importantly he knew what his customers liked, which goes some way to explaining why they held him in such esteem. But success and financial security had not come easily to him; he had experienced early, and hurtful, setbacks both in his domestic and in his business life, which left him wounded.

This sensitive man knew the fragility of happiness, was acquainted with Kipling’s twin impostors, and for this, prioritized his family before all else. He was conscious of the immense support his second wife, Kate, afforded him, and he always spoke with great pride of the achievements of their two children, Polly and George. He especially valued their holidays together in Italy, France, and Cornwall. Indeed, George wrote a most moving poem about his memory of this special quality time, which was read out at the funeral. It finishes:

“If I had one more day I would want to say goodbye.”

Selfishly, I, too, think of the sins of omission, the bottles – sorry, Bill, magnums – we had planned to drink together, the unfinished conversations, the joie de vivre eclipsed. For this was a man larger than life. In the words of the Nunc Dimittis, which Bill would have sung in Chapel:

“Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word.”