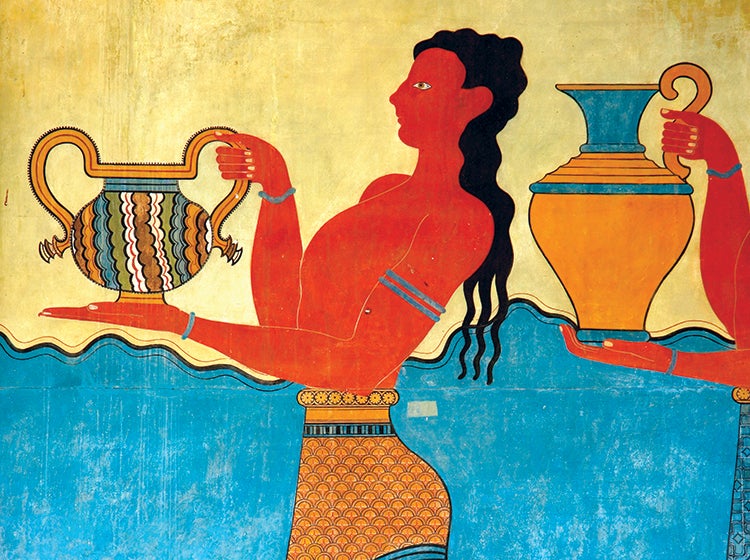

The terrain is rugged and unassuming; Russian tourists trawl the beaches when they’re not buying fur coats even in the middle of summer. The surrounding waters sparkle a sapphire blue-green, yet not far from the beaches and scraggly villages the land itself seems less exalted: hilly and untamed, neither lush nor desert, forest and scrub occasionally part to reveal olive trees and vines. The land is old, as is the culture; Minoan ruins testify to an advanced ancient civilization from the Bronze Age. Amphorae at the Palace of Knossos, on the north side of the island, witness ancient winemaking traditions and culture. But Crete’s wines today reflect little of that ancient heritage.

Ruled successively by Dorian Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Venetians, and then the Turks, Crete became part of modern Greece only in 1913. The country’s largest island, its population holds their identity dearly, and its wine producers are keen to give Cretan wine a distinctive identity as well. A small group of growers is working to change the perception of Cretan wines, to establish itself as a quality region, to create a niche within a niche. Some retain remnants of the past to build the future; others build the future to remember the past.

There’s no shortage of challenge here, but that’s not to say there’s no promise. Phylloxera came relatively late to Crete; it was not until 1974 that the louse first appeared to ravage the vineyards. Fortunately, by that time, the solution to phylloxera was clear. Growers set about grafting cultivars and replanting vineyards. Unfortunately, almost all old vines of indigenous varieties have been lost, and today the overwhelming majority of wines are grown from relatively young vines. That Crete’s more intriguing indigenous varieties, such as Kotsifali, Liatiko, and Mandilaria, need considerable vine age to produce wines with character and weight, is just one of several clues that the island’s best wines are yet to come.

Many factors impeded Cretan wines from attracting world attention. Key among them is the absence of a fine-winegrowing tradition on the island. The local population purchased wine in bulk, never developing a palate for fine wine. Cooperatives dominated the industry throughout the 20th century, with the familiar consequence that farmers — who were required to join the cooperative — had no incentive to curtail yields. Thus Crete became associated with bulk-wine production; Crete still is currently responsible for 20 percent of all Greek wine. To the degree that the authorities supported an indigenous variety, designed to offer a point of difference, they promoted plantings of Vilana — a neutral, innocuous variety, but not one likely to rivet anyone’s attention, even more so as it fell victim to overplanting and overproduction. As if these factors alone weren’t enough, the absence of any university or Cretan enological center exploring or encouraging vinicultural research was yet one more element militating against the development of a quality culture. It was not until the 1990s that a small number of individual producers decided to forge on independently, to replant both indigenous and international varieties, and to set themselves toward producing quality wine. Today, there are roughly 30 producers bottling estate wine independently. This small group, most of whom studied viticulture and vinification in Athens (though a few have studied in France, Italy, or California), have great hopes, often blended with a sweet innocence, about their wines and their potential.

The mountains that roughly divide Crete into two, north from south, are critical for viticulture. The 50,500ha (124,788 acres) of vineyard land lie mostly on the northern side of the island, where the mountains not only buffer the hot African winds but also offer mountain breezes and higher-altitude planting sites. Rather unusually for a viticultural region in the northern hemisphere, most of Crete’s vineyards are northfacing. Thus, while Crete is Greece’s farthest extension to the south, it is not the country’s warmest appellation. The soils are varied, though most vines are rooted in areas of calcareous clay often mixed with sand, and there are areas of schist and granite. There are four distinct quality-wine appellations (PDOs), but as elsewhere, appellation is no guarantee of quality; rather, it is the individual vintner’s experience and overall commitment that together deliver the more promising wines produced today.

The grape varieties

Curiously, for an island with such an ancient culture, relatively few indigenous varieties survive. Among the whites, most producers have focused on the Vilana variety, planted all across the island, thereby making it the most important white variety on Crete today. PDO Peza White must be 100 percent Vilana; PDO Sitia White, while based on Thrapsathiri, may have up to 30 percent Vilana. Though its proclivity toward high yields often leads to bland, innocuous wines, with attentive nurturing, it can produce vibrant, aromatic wines with aromas of citrus, raw almond, green apple, a delicate mineral thread, and occasionally a whiff of spice. Vilana’s vitality and interest are heightened, however, when sourced from dry-farmed, highaltitude vineyards and blended with other varieties — not just Thrapsathiri, but also Vidiano, Moscato (and even Sauvignon Blanc). More growers are paying increased attention to these latter, arguably more expressive varieties, each having its own champions. Thrapsathiri, now known to be a different variety from Athiri, may stand alone as a varietal wine, but many blend them; at Domaine Paterianakis, 12 miles (20km) south of Heraklion, winemaker Emmanuela Paterianakis blends it with Sauvignon Blanc; several others, with Chardonnay or Vilana. Vidiano and Plyto are two varieties that were practically extinct but have been replanted recently and show promise. The Lyrarakis family began replanting the early-ripening Plyto in the late 1980s and are its main producers, though Domaine Tamiolakis blends 30 percent Plyto with its Vidiano, creating a serious wine with breadth, texture, weight, and hints of petrol among the fresh tropical fruits. The Moschato Spinas (Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains), though more difficult to vinify — it oxidizes easily, needs a lot of protection, and can lose its delicacy quickly — is delightfully aromatic and elegant. All of the whites do better at higher altitudes, on windy slopes, where the airflow is fresh and yields are controlled.

Among the red varieties, the most important include Kotsifali, Mandelaria, and Liatiko. The first two typically are blended together, as required in the Peza and Acharnes appellations. Pomegranate-scented with smoky undertones, Kotsifali is soft and broad on the palate, with sweet, gentle tannic structure. Mandelaria offers a firmer structure in terms of acid and tannins, with red fruit and mineral aromas; when vinified as a rosé, it can be meaty, chewy, and earthy — but the yields must be strictly controlled to ensure phenolic ripeness. The earlyripening Liatiko is used for both dry and sweet wines, as in the Dafnes appellation in the center of the island, though its pale, unstable color browns quickly; one can understand the inclination to blend these three indigenous varieties with Syrah or Merlot to provide fresher color and aromas. (The producers — that is, the cooperative — in Sitia agitated to amend their appellation laws in 1999 to require that 20 percent of Mandelaria be blended with Liatiko to give the wines a bit more color and heft. Yannis Economou disputes this rationale, however, and avers that well-tended Liatiko can do very well on its own, thank you.) While there are a few Cretan producers, such as Lyrarakis and Economou, who have focused primarily on these indigenous varieties, others have taken to blending them with Syrah or, occasionally, with Merlot or Cabernet Sauvignon.

Regions and producers

Of Crete’s four districts, Chania lies in the far west and is the coolest, thanks to sea breezes emanating from the Mediterranean. The district itself had no winemaking identity before being designated a PGI in 2010. Romeiko is Crete’s most planted red variety, but it is authorized for white, rosé, and both dry and sweet reds. It is primarily used for sweet wines and the classic Marouvas, a local specialty in the Vin Santo vein. Grapes destined for this last are typically harvested at about 15-16% potential alcohol; after five or six days of maceration, the juice is racked into a chestnut barrel and left with about 15 percent ullage for a minimum of four years. Often the wines were subject to temperature variations, it being cool in the winter and hot in the summer. Oxidative, with varying degrees of sweetness, but not necessarily lacking in acidity, the wines can be sinewy, with notes of torrefaction, nuts, and caramel, but alive with a surprising core of fresh stone fruit.

The characters of the three main domaines vary widely. Andreas Dourakis studied enology in Germany and was working in Thessalonika when, in 1988, he returned to tend his father’s vineyards in the foothills of the Lefka Ori mountain range. Now working with his son Adonis (who studied at Geisenheim), he produces whites, reds, and sparkling wines from both estate and contracted fruit. (Their own vineyards are organic.) The whites, based on Vilana and Vidiano, are superior to the reds. The domaine has grown incrementally, so as not to be under the bankers’ boot, so it could benefit from added investment.

Trained in chemistry and enology, Manolis Karavitakis did his time at the two local co-ops before founding his own winery in 1998. Like Dourakis, the reds from Karavitakis are based on European varieties but from a greater array: Plantings include Syrah, Carignan, Grenache Rouge, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Tempranillo — even Sangiovese and Nebbiolo, since Manolis had studied in Naples in the mid-1970s. The raw material shows promise, and the spanking-new facility demonstrates considerable investment and aspiration, but recent bottlings suggest an excessive allegiance to an oppressive oak regimen.

Nostos, the Manousakis Vineyards and Winery in the far northwest of Crete, is of a very different history and order. Born in Crete but shipped to the USA when he was 11, Ted Manousakis built a successful security-services business in the Washington, DC, area before he returned to rebuild his grandparents’ home and, beginning in 1993, embarking on what is one of the most ambitious projects in Crete. Manousakis’s project is rooted in the Greek word for “nostalgia,” which originally referred to a yearning to return to one’s homeland. Yet the foundation here is not old vines. To determine how best to capture the potential of his Kissamos District vineyards, he corralled an international all-star team of consultants, from Lucie Morton (USA, rootstocks), to Lorenzo Naini (Bologna, trellising), to Pascal Ferrand (France, winemaking). On rolling hills, mostly of sandy soils 985-2,130ft (300-650m) above sea level, he initially decided to focus exclusively on red and white Rhône varieties, unique for the region at the time. From 1998 onward, the kind, earnest Kostis Galanis has directed the winemaking. Following viticultural studies in Montpellier, Galanis returned to Crete to work in the cooperative, all the while believing the island was capable of better. He found his niche with Manousakis. The flagship Nostos white is 100 percent Roussanne: Consistently fragrant, broad, and creamy, green fruit and melon flavors co-mingle with wellintegrated toasty notes. The Nostos Alexandra’s blend of Syrah, Mourvèdre, and Grenache is designed for fruit from younger vines and to ensure the quality of the top wines. The Nostos red, a blend of the major Rhône varieties, tends to be full-bodied, chewy, and ripe, leathery and spicy; a little volatility hints at the wine’s rustic roots but offers lift and verve.

The Manousakis crew recently embraced local varieties; their new, entry-level wine is a blend of Vidiano, Vilana, and Assyrtiko; a Romeiko is en route. The team is as international as it is inter-generational now that Manousakis’s youngest daughter Alexandra shucked a real-estate career in the States for the wilds of Crete, allowing her father to run the project more remotely. Remote is indeed the operative word here: The property in the hamlet of Vasolakkos does feel far away from much of the world, which may account for the warm bond that palpably links the core Nostos team together. The prefecture of Iraklio (Heraklion), in the center-east of the island, is home to three of its four quality wine appellations: Dafnes, Archanes, and Peza. As such, with the greatest number of commercial wineries, this region could be said to be the epicenter of the Cretan quality-wine revival. Yet while there are some clean, pretty wines from Dafnes and, increasingly, from Peza, overall one has more the impression of youthful producers, brimming with hope, determined to forge a new path notwithstanding the absence of noble tradition. To date, however, as they experiment with blends, extraction methods, élevage, and wood regimes, this writer is hard pressed to find a single producer with consistent quality across their full range.

Nevertheless, bright spots exist. One of the more intriguing producers in Peza is Lyrarakis, which began bottling its own wines in 1992. Working with its own 14ha (34 acres), as well as contracted grapes, its range includes ten varietal wines. The more intriguing wines include the Plyto, a variety that was almost extinct until the family replanted it in the late 1980s. The 2011 was lightly textured with a delicate minerality, offering surprising depth and length for such a light wine; a creaminess on the palate gives way to a crisp, nervy finish. Another curious variety is Dafni — a big, thin-skinned grape whose name means “bay leaf”; with loose bunches and thick skins, it ripens a month later than other varieties. The herbal aromas ring true to its name; the palate is a bit oily, though fresh and crisp, with a nervy finish. And their dry-farmed, Plakoura Vineyard Mandelaria throws down the gauntlet to those who disparage this variety: Flavorful and juicy, still shy of jammy, it offers notes of wild strawberries supported by firm acidity and supple tannins.

Other promising family producers include Tamiolakis, driven by the brother-and-sister team of Manousos and Maria. Both siblings studied in France and make their wines, grown on calcareous clay soils, informed by a French sensibility of quality and balance. (No doubt the windy conditions contribute their wines’ freshness and energy.) Additionally, the Minos-Miliarakis winery, established in 1932 but having suffered from a shaky evolution, seems invigorated. Both of these domaines are producing a variety of delightful white wines; the work each is doing with Vidiano suggests that this variety, with its lightly oily texture, fresh aromatics of yellow fruits and citrus, and crisp acidity, can lift not just a dish of grilled fish or seafood but world perceptions of Cretan wine. Additional promise is perched along the terraces of the vertiginous, wind-swept Diamantakis vineyards, were Zacharias and his two brothers have converted a small distillery into a working winery. All of these producers are working with Kotsifali or Mandilaria, blending these varieties with Syrah or Cabernet Sauvignon to add depth and structure. Finally, one would be remiss not to note that from within the bowels of a wine refinery, small gems can emerge: The Alexakis family, owner of the largest privately owned winery in Crete, has long produced high-volume wine. In the late aughts, however, brothers Apostolos and Lazaros, who studied enology in Fresno and Florence respectively, decided to launch a quality line on their own. Their dry Vidiano shows fresh fruit, electricity, and nerve; “Thistle” (Athiri) is firm, minerally, and saline; and the Syrah/Kotsifali blend has a sturdier framework than most Cretan reds, complemented with a refreshing complexity on the palate.

In the far east of the island lies the prefecture of Lasithi, which, even if it has the smallest area under vine, has some of the most provocative wines on Crete today. Lasithi stretches east from Mt Dikti, after which the island narrows to a point only 12 miles (20km) wide. This is Crete’s driest and warmest region, with only one OPAP zone, Sitia. The soils are varied, sometimes a fossil-strewn marl, perhaps with elements of sand, iron oxides, schist, and limestone. Apart from the cooperative, the Toplou Monastery has been producing wine since 1999. Its organically farmed vineyards are only 820ft (250m) from the sea, at 820ft above sea level, but recent selections have been disappointing.

The real excitement of the prefecture resides at Domaine Economou, on the Ziros Plateau, a 20-mile drive south from the town of Sitia on the island’s north coast. At 1,970ft (600m) above sea level, Yannis Economou farms 80- to 90-year-old ungrafted Liatiko vines, along with Mandelaria, Vilana, and Thrapsathiri, and more recent plantings of a few French and Piedmontese varieties (Grenache, Merlot, Nebbiolo, Barbera) — presumably a holdover from his education and earlier stages. (After receiving an enology degree from Alba, Economou worked in Piedmont at Ceretto and Scavino, consulted in Germany, and spent a year at Château Margaux for the difficult 1993 vintage before returning to Crete to take over his grandfather’s property.) A bit of a renegade, Yannis is opposed to the change, since the 1999 vintage, that a 20 percent dollop of Mandelaria be included in Sitia red. He contends that the local co-op persuaded the authorities to institute the change, since Mandelaria’s sturdy tannins would bolster wines produced from Liatiko cropped carelessly, greedily, or grown on lesser sites. Economou produced a 100 percent Liatiko before 1999, and if he’s not happy with the Mandelaria he’s grown, he’ll sell it off and bottle his wine outside the appellation, as he did with the 2006 vintage Economou’s wines are idiosyncratic, since he produces one-offs and is vintage-respondent. He is not one who believes a red wine needs deep color to convey gravitas or longevity. Organic viticulture, spontaneous ferments, minimal sulfur, and extended élevage in barrel (primarily old, from Burgundy) or tank are but a few of his guidelines. His current release, the 2006 Liatiko, releases a lovely perfume, reminiscent of red Burgundy, with spices, cherry blossom, and minerals; the middleweight palate is dynamic, tense, and nervy, delivering first a flash of licorice and dark berries, supported by delicate, Nebbiolo-like, dry tannins, leading to a taut, energetic finish. It’s approachable now, though necrophiliacs may prefer to wait. His 1999 Sitia (legally compliant with 20 percent Mandelaria) is similarly dynamic: The nose exhibits a focal core indicating its reductive strength; on the palate, it’s persistent, firm, and crisp with an impression of struck flint; firm tannins add sinew and edge to a warm finish. These wines aren’t chockablockbusters; still, they benefit from decanting to soften their tannins and release their perfume.

Notwithstanding its ancient history, contemporary vinous Crete is still finding its way. There can be no doubting the commitment, focus, and desire to succeed on the part of the producers. Relatively speaking, the industry is young, hopeful for its future, and steadfast in its belief that Crete can offer distinctive quality wines that are as full of character as the people themselves. With this sort of commitment, as vines and growers continue to mature, we can believe that the best is yet to come and that, in the future, the wines will shine as brilliantly as Crete’s surrounding seas.