Mike Jay

High Society: Mind-Altering Drugs in History and Culture

Published by Thames & Hudson

$19.95/ £18.95

Reviewed by Stuart Walton

Who will ever relate the history of narcotica?” asked Friedrich Nietzsche in The Gay Science (1882). “It is almost the history of culture, of our so-called higher culture.” Rigorously handled intoxicant histories may have awaited their golden age until around a century after he posed the question, but they are now indubitably in full spate. The present volume was published to coincide with an exhibition of the same name at the Wellcome Collection in London in November 2010 and is an ingeniously condensed, elegantly written, and superbly illustrated addition to this copious literature. Part of what has driven widespread interest in the subject, apart from the truism that nearly everybody likes a drink, is the more or less complete unlocking of the taboos surrounding proscribed intoxicants, at least in western societies. There is a mostly relaxed, even slightly thrilled awareness in society that a substantial minority of its citizens consumes controlled substances-a fact reflected in popculture references to drug taking and undoubtedly bolstered by the selective tolerance with which Western jurisdictions are prepared not to enforce their own prohibitions.

The moral panics of earlier eras may have abated, but what remains in their stead is a profound ambivalence about the ethical valences of intoxication. In the early years of the last century, the German sociologist Max Weber argued that at the heart of capitalist society lay an antagonism between the profit incentive and the enactment of what his contemporary Thorstein Veblen famously labeled “conspicuous consumption.” Making money was good, as long as you didn’t waste it on self-indulgences. Keeping sensory desires on a tight leash assisted civilization. The only problem was that the widespread disenchantment created by mechanized labor, and its sparsely functional lifestyle of saving up, reinvesting, and budget balancing, had reduced most people’s lives to a spiritual sterility, which could only be relieved by recourse to the most crudely instrumental psychoactive means.

If the need to keep one’s head above water in a viciously competitive society gradually displaces life’s more transcendent moments-be they encounters with the natural sublime or with great art, the joy of personal relationships or the transports of religious faith-all that is left is direct intervention in the neural pathways, for which an entire pharmacopeia of new synthetic materials had come into being to supplement age-old natural intoxicants. On Weber’s reading, it was this enforced overinvestment in alcohol and other drugs-like opium and its first synthetic alkaloid, morphine-that turned them into social problems. That in turn led to the formulation of what became the first international protocol on proscribed substances.

Fascinating threads

That is about the best account that any work of intoxicology can offer of the Western experience of the past 150 years, and Jay does not scant it here. He traces fascinating threads through that story, pointing out, for example, that synthetic sedatives, all the way up to Bayer’s patented cough suppressant Heroin, long provided the narcotic paradigm for sportive intoxication, before the world was changed by the arrival of synthetic stimulants with cocaine, for which a hyperventilating Freud wrote pharmacology’s most notorious PR copy (“the most gorgeous excitement […] exhilaration and lasting euphoria”).

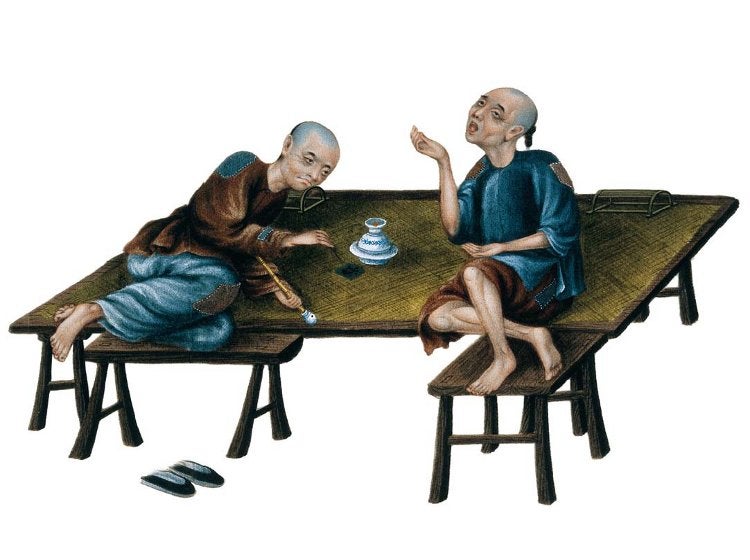

Western dysfunctionalism is never the whole story, though, and so our attention is also referred to the sacramental use of plant hallucinogens in tribal cultures of the Amazon Basin and Mesoamerica, to the medicinal applications of intoxicants in antiquity, and to the surprising appearance of drugs as markers of social status, even amid general prohibition. Not all the opium usage in Qing Dynasty China took place in squalid dens; there were also more lavishly appointed opium houses, where rich merchants and civilservice Mandarins might light a jadeencrusted pipe amid an ambience of exquisite courtesies and silk cushions, the opium itself matured to mellow potency in cellars, as Vintage Port is.

In response to the proliferation of laboratory-designed materials, such as the spectacularly successful mephedrone, drug legislation is once again arrogating to itself the kinds of all-subsuming powers that contributed to the present legal disarray in the first place. We are entitled to wonder all over again whether there can ever be such a thing as a drug-free society, one no more in need of biodynamic Pinot Noir than it would be of crack.

The idea may have been confidently rubbished as recently as ten years ago, but it figures in revolutionary ways in the conversation about the “post-human condition” in which contemporary neuroscience is engaged.

Might it be possible to tool an advanced generation of digital and cybernetic devices to produce direct stimulation of the neurotransmitters in our brains, mimicking the effects of psychotropic drugs without risking the attendant physical harms of their chemical predecessors? Might, as Jay puts it, “heightened consciousness become a permanent, even universal state?” And how would we tell it apart from the non-heightened variety?

What intoxication offers is a release from default consciousness, even to those caught on addiction’s dreary treadmill. A permanently medicated population-whether the agent of its contentment be Prozac, some other Huxleyite medicament, or a battery of smartphone apps-will sooner or later seek an obvious outlet. That may come in the evil shape of unscrupulous freelance pharmacologists cooking up ever-more-noxious designer drugs. Or perhaps the most euphoric antidote of all to a life lived in virtual reality will turn out to be reality itself.