Jean-Paul always took great interest in the sourcing of natural raw materials – sandalwood and jasmine from India, rose de mai from Grasse, and geranium and palmarosa from Madagascar, for example. Today he continues to develop his ylang-ylang plantation in Mayotte and orange-blossom factory in Nabeul, Tunisia.

An accomplished equestrian, Jean-Paul competed at international level, twice qualifying for the French Olympic dressage team. He also trained as a cordon bleu chef. He lives at the family estate in Les Mesnuls, near Paris, where he maintains a suitably aromatic jardin de senteurs. Did you always have a vivid awareness of smell, even as a child?

I think so. My first perfume memory is linked to a strawberry tart that my mother cooked for my birthday. It was during World War II and I was four years old. I can still see my mother preparing this dessert, a rare treat in those times. Since then, the scent of strawberry tart has always, for me, conveyed the essence of tender affection – a homely, ordinary fragrance, but one that still moves me today.

Later, when I joined my grandfather, Jacques Guerlain, at the age of 16, I had a huge problem with my eyes – in fact, I was nearly blind, so I followed him like a little dog. He saw I loved to smell. He taught me everything – to look for the beauty in every object, the love for the best natural raw materials, the power of memory. He also sent me to England to improve my English. I stayed with Sir Frédéric Hennessy and his two daughters. During my holidays, Sir Frédéric had invited some specialists for a tasting. He asked me to join them, which I did eagerly, even though I had never tasted Cognac before! And I astounded everyone present by picking out the best one – a 1911 vintage – simply by smelling it.

Can you explain the influence of smell on the psyche?

The sense of smell is one of the most important in our lives. When a baby is born, he recognises his mother through her smell. And at the beginning of our human evolution, smell was a way to find food, to recognise the animals and so on… Nowadays, smell is the poorest sense, and it is very sad. We pay a lot of attention to the others senses – such as taste – but smell is completely forgotten.

Perfume is so important because it has the extraordinary ability to conjure up forgotten landscapes and experiences from the very depths of our memory and to bring a person you have loved vividly to life again. It is the most intense form of memory. It is also a fragile, tenuous link between the person wearing it and those who smell it. It expresses what is not said, weaving a halo of light that allows the wearer to go out into the world enveloped in a protective veil.

Do you think that heightened sensory ability – particularly smell and taste – is innate, or can it be refined with practice?

Of course there are people with a highly developed sense of smell but, generally speaking, everybody can smell adequately. But smell and creation are two totally different things. It is as with musicians: most of them are able to play the piano well, but only a very few can create symphonies. I was trained to do both things – to recognise and remember smell, and also to work with my imagination in the creation of perfumes. The second is more difficult, of course.

The first part is work – smell and smell again, all day long. I remember my grandfather setting me up in a small room, about 6ft [1.8m] high. The row of products arranged alphabetically on the shelves started with amyl acetate and ended with wintergreen. There for days, indeed months, I learnt to recognise and memorise nearly 3,000 different smells of natural and synthetic raw materials.

Recognising every nuance demands a great deal of practice and tenacity. Even now I have to train my sense of smell all the time – otherwise it gets poor. It may be relatively easy, after some trial and error, to link the name of a plant or flower with its perfume, but things get more complicated when you have to find a personal image that will allow you to identify a synthetic product with a highly technical name. In this case, the key is to stick with the analogy you chose for yourself at the outset and not to change it, even if the terms you have chosen do not work so well for another fragrance. After this, at every stage of creating a perfume, the imagination will come up with combinations of fragrances, proceeding from one trial to the next in order to achieve a fragrance that is unexpected, original and sensual.

Can you describe the process of creating a perfume?

Creating a perfume gives me intense sensual pleasure. I lose myself in the process, and it is only then that the fragrance begins to take shape. In this exhilaration, my ideas grow and develop. I circle around the fragrance and even inside it. I leave my dreams in a succession of olfactory visions.

You first create the perfume in your mind, then try to manifest this idea. A fragrance should not force itself on you – it must be the expression of a precise emotion, and after a certain amount of trial and error it comes to resemble the abstract image. My grandfather used to say that a successful fragrance is one in which the scent exactly matches the dream or vision that inspired it. It is the story of a sublime and sensual passion.

My point of departure may be a smile, the fragrance of a woman’s skin or the fleeting vision of a face. Every one of our fragrances was inspired by a muse. Behind Mitsouko, Shalimar, Samsara, Nahema, you find yourself in the presence of a woman who was loved or admired.

Who were these muses?

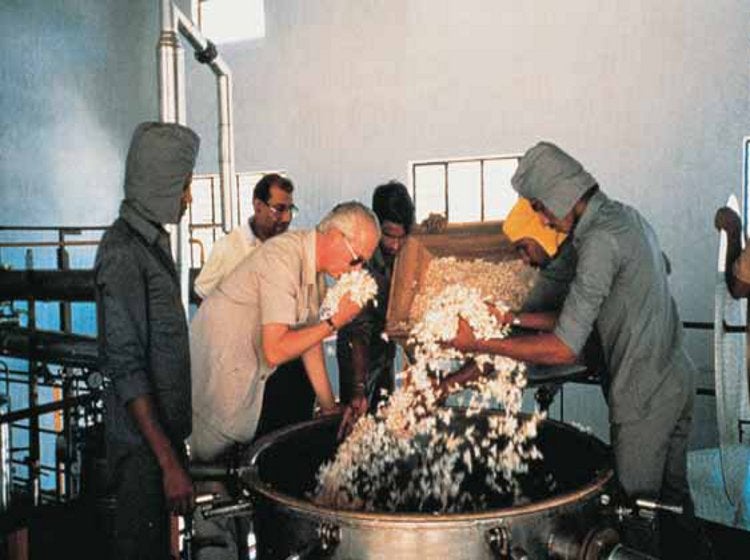

Samsara was created for an English woman who shared my life for many years. She did not wear perfumes, but she loved sandalwood and jasmine. Happy with my muse’s choice, I set to work. When I presented my first trials to my uncles, they were not convinced. I continued working, carrying out trial after trial, trying to come up with other fragrances. In the end, I had more than 300. To make Samsara, I wanted a special jasmine that was used in Indian temples but not in the perfume industry. Jasmine is a delicate flower that needs handling with care. It can’t travel easily, and such journeys would have affected the quality of the product. With a French supplier, we decided to build a factory in India, on the plantation itself. What might at first have seemed a crazy idea became a great reality, and I was in charge of supervising the manufacturing process. I still go twice a year to the plant in the town of Maradur.

With Vetiver, the men’s fragrance, it was different. We needed a sophisticated vetiver-based fragrance, since we already had a product made around this raw material for the Mexican market. My grandfather had no real interest in the project, so he decided it was a good one on which to cut my teeth. I was only 18 years old at the time and was helping a friend to create his garden. I was assisted in the task by a wonderful old gardener, dressed in a jacket of coarse black serge and brown velvet trousers. He smoked Gitanes, and the mingled smells of tobacco and earth impregnating his clothes had a strong influence on me as I put together the formula.

Shalimar was created by my grandfather, Jacques. The Gardens of Shalimar in Lahore were created by Emperor Shah Jehan for his wife Mumtaz Mahal; he also built the Taj for her. My grandfather never went to India, but he created Shalimar based on the inspiration of this romantic Mogul story. His vivid imagination, allowing him to shape his own reality, had done the rest.

Do you feel any affinity with a winemaker?

In perfume-making, as in winemaking, the basis is know-how and method, and both wine and perfume must express their own character. They must be memorable and pleasurable. The links stop there, however, because the range of flavours is much more limited than that of smells.

Some feel that wine tasting can never be an objective science. Do you think subjectivity has a place in sensory analysis?

When I create a fragrance, it is always for a specific woman with her specific size, colour of hair and eyes, personality and so on. My choice of the raw ingredients and my combination of them are completely subjective; I choose them because I like them.

Powerful, concentrated wines have found fashion recently. Do you see parallels in fragrance trends?

I am really not very fond of trends. For me a good perfume is a perfume that smells nice, is memorable and lasts in time. It’s difficult for me to talk about trends, when Shalimar, created in 1925, is still one of our best sellers, and Jicky, which dates from 1889, has always performed well too. I know we have studies about trends, but one has to guard against a result where all the perfumes smell the same and all wines taste the same! I never followed that path.

Which wines do you enjoy?

I love wine, and my cellar, without being exhaustive, contains 3,000 bottles, with cru Burgundy and Bordeaux, as well as regional and foreign wines. The only criteria are that they taste good, that one enjoys drinking them and that they go well with meals.

I started to drink wine when I started to cook. I was just married, about 24 years of age, and my wife did not cook at all. I learnt to cook and, at the same time, discovered wine. My first love was white Burgundy, and Domaine Leflaive, Robert Ampeau and Bernard Morey would still be among my favourites today. There is, of course, enormous variation from vintage to vintage and, indeed, variation in quality, even among the better producers. One can be disappointed. But a great white Burgundy is layered with complexity and also works so well with food.

Another early love was the softness of Loire wines. I liked the taste of Chinon and still appreciate them very much. Cabernet Franc can carry such fragrance.

A few years ago, I discovered the wines of my friend Bernard Magrez, the owner of Pape-Clément. Recently, I had a bottle of the 1990 – it showed excellent concentration, but the finesse was there too. There is not much in Bordeaux to rival the monastic history of Burgundy, but Pape-Clément was of course an archiepiscopal property. In 1999, I was made ‘pope’ of Château Clément, which I found extremely amusing.

I also enjoy Rhône wines, and they are getting better and better. I like Chapoutier’s Saint-Joseph, as well as Châteauneuf, particularly Beaucastel, and Henri Bonneau’s Réserve des Célestins.

And if you were to choose one wine that stands out in your memory…

What a difficult question! I have had so many good experiences that it is quite difficult now for me to single out one. But I remember one that I had a few years ago. I was invited to dinner by a friend in the South of France and we had Pétrus 1947. It was impressive. 1947 was a great vintage, slightly better than 1948 and far superior, in my view, to 1949.

The Pétrus taste is, for me, quite strong – it’s powerful, it’s intense. Yet although I am extremely partial to Pétrus, the prohibitive cost prevents me from consuming it in any great quantity. I relive the taste of the 1947 wine often – and I think that is because my friend served truffles with it. Truffles are the key – they evoke the memory. Whenever I talk about truffles, I can still smell that Pétrus.