When the curtain dropped at the Ethel Barrymore theater in New York at the end of the premiere of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, the audience sat in stunned silence. It then erupted, according to contemporary accounts, into a tumultuous applause that lasted for some 30 minutes. Those in attendance at the Barrymore that December 1947 evening, knew they had witnessed something radically new in American theater.

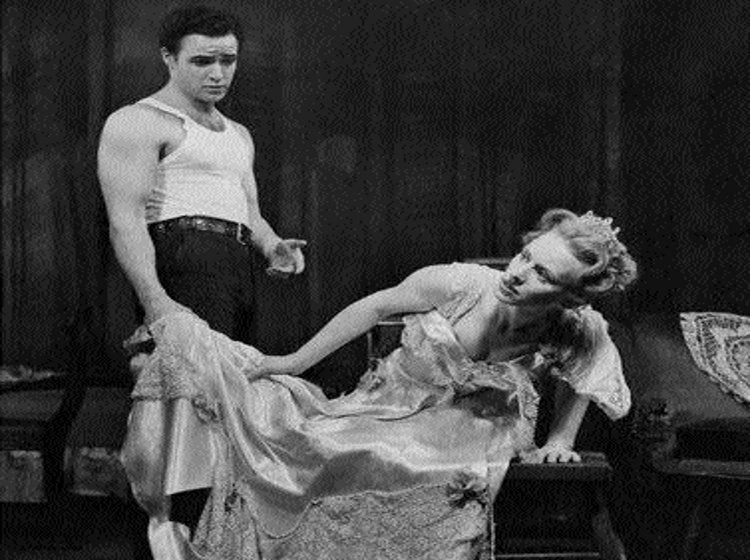

Williams’s play, under the direction of Elia Kazan, with its frank and realistic presentation of male and female sexual desire, nymphomania, homosexuality, and rape, and set in the gritty, sweaty slums of New Orleans, was both exhilarating and shocking. Marlon Brando, who played Stanley Kowalski, strutted around the stage in very tight jeans and a T-shirt. He fascinated and terrorized his wife (Stella, played by Kim Hunter), his friends, and his visiting sister-in-law Blanche DuBois (Jessica Tandy).

The next morning the New York critics were ecstatic. The drama critic for The New York Post called the play “feverish, squalid, tumultuous, painful, steadily arresting and oddly touching.” 1 Harold Barnes of The New York Herald Tribune found it a play of “heroic dimensions.”2 In 1948, Williams was awarded the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award, and he received his first Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1948.

The play is centered on Blanche DuBois and her tragic downward slide into madness. But it is “Marlon Brando in a role six times smaller than [Tandy’s] who is the sensation,” commented David Thomson.3 Brando drifted into New York from Illinois in the early 1940s with a vague idea of acting, and his first big break came when he landed a minor role in the Broadway production of I Remember Mama. Brando hated the play but it paid his bills. His next role was in Sherwood Anderson’s Truckline Café. The play was a flop, but Elia Kazan saw Brando, invited him to study at the Actors Studio, and two years later recommended him to Williams for the role of Stanley. As Richard Schickel noted: “The part was his — forever […] since every actor who has attempted it since has had to compete against everyone else’s memory of’ Brando.”4 Coming from an entirely different upbringing, co-star Jessica Tandy was born in England. Her mother was a popular stage actress, and Tandy made her first appearance on the London stage in 1926. She played opposite Laurence Olivier and John Gielgud in Shakespearean productions, moving to America to continue her stage and film career. She won a Tony for her performance of Blanche and an Oscar 42 years later for her memorable role in Driving Miss Daisy (1989).

Since that opening evening, both the play and Marlon Brando’s stunning performance as Stanley Kowalski have taken on an iconic identity. Streetcar has been revived on Broadway numerous times. It has been performed more than 20,000 times before audiences worldwide, and in 1951 Warner Bros released a movie version — starring Brando and Vivien Leigh, and directed by Kazan — that swept the Academy Awards in 1952. In 1984, Ann- Margret starred in a television version for CBS Playhouse; André Previn wrote an opera that was performed by the San Francisco Opera Company; it has been performed as a ballet; and to illustrate its popularity across generations, a musical version of the play — Oh! Streetcar — featured in “A Streetcar Named Marge,” a 1992 episode of the popular television program The Simpsons.

The author and the director

Tennessee Williams’s dark, perverse, violent, and often depressing view of human relationships exploded on to America’s literary landscape in the late 1940s. Williams, now widely recognized as one of America’s most gifted writers, was, in the 1940s and ’50s, one of its most controversial.

Born in Mississippi in 1911, Williams suffered an unhappy childhood — his father was domineering, drank heavily, and fought with his strong-willed, puritanical wife. Williams preferred poetry and writing to football, which caused his father to brand him a “sissy.” As the Depression tightened in 1934, he set out, like tens of thousands of other Americans, for California. This first trip to that American fantasy land brought no fairytale recognition from the dream factory. Williams lived in the shadows of the studios, forced to work a series of odd jobs to pay his rent. His first big break came during World War II, when MGM signed him as a studio writer. When he was assigned to write for child actress Margaret O’Brien, he rebelled. “Child stars make me vomit,” he told his bosses.

Williams first came to national attention on Broadway. In 1945 his play The Glass Menagerie began an 18-month run, and Williams was recognized as Best Playwright by the New York Drama Critics’ Circle. Two years later, Streetcar established him as one of America’s most gifted writers.

Williams, like Arthur Miller, wanted Elia Kazan to direct his new play. 1947 was an incredible year for Kazan. On Broadway he directed Miller’s All My Sons, which Williams greatly admired. While Sons was playing, Kazan dashed across the country to Hollywood and directed three movies — The Sea of Grass, Boomerang!, and Gentleman’s Agreement. For the latter he won the Academy Award for directing. He also managed to find time in 1947 to be one of the founding members of the Actors Studio, where he taught classes based on Konstantin Stanislavski’s naturalistic “System” to aspiring actors such as Marlon Brando.

Williams and Kazan were a perfect match. Both believed that the theater could be used as a social vehicle to present political, social, and ethical issues to diverse audiences. Kazan had been a member of the Group Theater in the 1930s and had flirted with communism. The two men collaborated on the production, and Williams urged Kazan to bring balance to Streetcar. “Blanche must finally have the understanding and compassion of the audience. This without creating a black-eyed villain of Stanley.”

The play

A Streetcar Named Desire opens as Blanche arrives in New Orleans. She is shocked to find herself in the squalor of the city’s slums and her sister living in a cramped, shabby two-room apartment with her husband, Stanley, a World War II veteran trying to adjust to a postwar America.

On the surface, Blanche seems to be a woman of some refinement — she is a teacher, has come with a trunk full of fine clothing, and until very recently has been living on the family estate, Belle Reve, in Laurel, Mississippi. She has all the affectations of a fine Southern woman and immediately makes no secret of her disapproval of the brutish, hard-drinking, violent, crude “Polack,” Stanley Kowalski. Blanche “puts on airs” in the Kowalski household and tells her sister: “He acts like an animal, has an animal’s habits! Eats like one, moves like one, talks like one!”

To Blanche’s horror she discovers that Stella really loves Stanley. She is pregnant, and while they have a violent relationship, Stanley’s power excites her sexually. One evening Stella and Blanche go out to dinner while Stanley and his cronies play cards. The men get drunk and the card game is still going strong when the two women return home. As they undress in the bedroom, Blanche turns on the radio. Stanley is furious that she would dare disturb his game, and he flies into a rage. He storms into the room and throws the radio out the window; and when Stella screams at him, “Drunk-drunk-animal thing, you!,” he punches her. Stella and Blanche take refuge in the apartment above them.

After his cronies put him in the shower to sober up, Stanley pleads for Stella to return. He stands at the foot of the staircase and screams: “Stellaaaa! Stellaaaa! Stellaaaa!” She hears his cry and responds by walking slowly and sensuously down the staircase. Stanley buries his head in her stomach, pleading forgiveness. They kiss passionately before he carries her off to bed.

Blanche is dumbfounded. When she sees they are going into the bedroom, she slinks outside the small apartment so she will not have to listen to them making love. The next day she scolds her sister for returning so quickly to this brute. Stella tells her simply, “There are things that happen between a man and a woman in the dark… that sort of makes everything else seem… unimportant.”

Stanley may be crude and violent, but he is no fool. He suspects that Blanche has sold the family estate at a considerable profit and that he is entitled to a share of the money. Blanche tries to convince him that the family home was frittered away by her father and grandfather on “epic fornications,” but Stanley remains suspicious and begins to ask questions about his sister-in-law. He discovers, to his delight, that this delicate Southern flower is running away from a very sordid past.

Blanche, it seems, was married at a tender age to a young boy who wrote poetry and was extremely sensitive and tender — different from other boys. One evening she discovered how different he was when she walked “into a room that I thought was empty — which wasn’t empty, but had two people in it… the boy I married and an older man who had been his friend for years.” That evening, after Blanche confronted her husband, he committed suicide.

It drove Blanche into her own world of debauchery. She took to the bottle and admitted to Mitch (played by Karl Malden), a friend of Stanley’s who had fallen in love with Blanche until he found out about her past, that she had “many intimacies with strangers” and was run out of her teaching job in Laurel after the school authorities found out she was having an affair with a 17-year-old boy.

The audience soon discovers this was no passing fancy. Blanche, haunted by the memory of her dead husband, is still sexually attracted to young boys. When a young man comes to collect for the newspaper, Blanche is overwhelmed by his beauty. She calls him over to her. “I want to kiss you — just once — softly and sweetly on your mouth.” She kisses him, then says: “Run along now! It would be nice to keep you, but I’ve got to be good and keep my hands off children.”

With her past fully exposed, Stanley has succeeded in destroying Blanche emotionally. He has driven away Mitch, her last hope for independence and respect, and then, as a final humiliation, he orders her out of the house. Blanche has nowhere to go. This hastens her descent into madness, and she begins to wander about the apartment fabricating a romantic story about an old suitor who has invited her on a cruise.

Stella suddenly goes into labor, and Stanley takes her to the hospital. When the doctors tell him that Stella will not deliver until morning, he returns to the apartment. Blanche is concerned that the two of them are alone in the apartment, but Stanley is delighted at the prospect of being a father and suggests that they “bury the hatchet.” But when Blanche continues to babble about her rich suitor, Stanley becomes so enraged that he brutally rapes her. The last scene of the play takes place several days later, and Stella has returned from the hospital with her baby. Blanche is packing for a trip. It is clear that she is emotionally disturbed, and Stella whispers to her neighbor: “I couldn’t believe her story and go on living with Stanley.” Her neighbor agrees: “Don’t ever believe it. […] You’ve got to keep on goin’.” Blanche is still under the delusion that she is going on a cruise with a wealthy admirer; the truth is that she is being committed to a state hospital for the insane. As a kindly doctor leads her away, Blanche says to him, “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

As Blanche is leaving, Stanley begins to console Stella. He holds her softly and in soothing tones whispers to her, “Now, love. Now, now, love. Now, now, love,” and begins to unbutton her blouse as the curtain drops.

In one play Tennessee Williams managed to assault almost everyone’s preconceived concept of what was permissible to discuss in public entertainment. The play contained homosexuality and rape, while the pivotal female character, Blanche, was a lush and a borderline nymphomaniac with a particular attraction to young boys. Stella was hardly the paragon of virtue that America envisioned for young wives and mothers. She and Blanche continually talked about sex on stage. Stella was verbally and physically abused by her husband but was so sexually excited by his raw power that she eagerly returned to his bed no matter what he did. In an era when “ladies” were supposed to be passive sexual partners, Stella was an enthusiastic participant. As Stanley told her, “I pulled you off them columns and how you loved it, having them colored lights going!”

The male “hero” in this slice-of-life drama was a sadistic brute who screamed at everyone, smashed furniture and dishes to prove a point, used his fists on anyone who stood in his way, raped if it suited his purpose, and insisted that his wife submit to his will. “Remember what Huey Long said — ” he screams at Stella when she asks him to help clear the table, “‘Every Man a King.’ And I am the king around here, so don’t forget it.”

The legacy

The play was a smash hit on Broadway, running for two years — some 885 performances. Even before the run ended, two touring companies began performing it to packed houses in Philadelphia, Buffalo, Boston, and beyond. Streetcar illustrated that Americans, who were used to censorship of popular entertainment, were ready to accept serious adult themes. Just over two years after the play opened, Hollywood announced it was bringing Streetcar to the screen. In 1951, the Warner Bros production hit American screens with the same stunning punch that theater audiences had experienced.

Hollywood producer Charles Feldman convinced Kazan to direct the film version of the play and approved all of the original Broadway cast members except for Jessica Tandy. Feldman wanted a movie star with marquee power in that role, so he turned to Vivien Leigh — Scarlet O’Hara in Gone With the Wind — who was starring in the London production of Streetcar.

Kazan originally wanted to bring the play out of the confinement of the proscenium arch. He developed a screenplay that incorporated Blanche’s downfall in Mississippi and added scenes for Stanley at work and in bars around the French Quarter — in short, turning the play into a film. But when he read the screenplay, he threw it out and decided “to photograph what we’d had on stage, simply that.” And so he did.

To be sure, there are some changes in the film that were demanded by the censorship system that existed for Hollywood films in the 1940s. In the film, the references to homosexuality are toned down, Stella’s sexual desire is softened, the rape is inferred, and, most importantly, Stella refuses to return to Stanley, fully understanding what he did to her sister. The censors refused to allow Stanley’s crime to go unpunished.

But the modern DVD versions of the film have restored all the scenes that Kazan originally shot (and the censors removed), and Brando, Hunter, and Malden, joined by Leigh, provide as good a view as is possible of what audiences saw in 1947. It is the film version that allowed millions of viewers to see what only a few thousand saw on Broadway.

Streetcar, the movie, was nominated for 12 Academy Awards and won four: Vivien Leigh for Best Actress, Karl Malden and Kim Hunter for their supporting roles, and the Best Art Direction honor went to Richard Day. Brando lost to Humphrey Bogart’s touching portrayal of a gin-swilling river-boat trader in The African Queen.

Modern reactions to the play are, of course, different. Kazan and others noted that audiences in 1947 often laughed at Blanche; they sided with Stanley — until he raped her. Stanley’s relationship with Stella is also seen in a very different light today. Spousal abuse, verbal and physical, is no longer acceptable. At one recent screening of the film version, a woman stated, “Stanley is a pig.” No one in the audience contradicted her assessment.

All the principals involved had long and successful careers. Williams won another Pulitzer in 1955 for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and his plays ran on Broadway and on the screen for the next two decades. Hunter and Leigh continued on the stage and screen. Neither ever again achieved the success reached in Streetcar. Kazan continued to make films, and he directed most of Williams’s future plays on Broadway. Unfortunately, he is most remembered today not for his directing talents but for his “naming names” before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1952. His Lifetime Achievement Oscar in 1999 was as controversial as his HUAC testimony in the 1950s.

Brando, of course, became Brando. He abandoned the stage for the stardom, money, and power Hollywood gave him. He reunited with Kazan in Viva Zapata! (1952) and won an Oscar for his portrayal of Terry Malloy in Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954), which defended ratting out your friends. Brando made lots of clunkers after Waterfront, but his Don Vito Corleone in The Godfather (1972) is one of the classic film performances of all time. A Streetcar Named Desire continues to be performed all over the world. The DVD version is used in English, theater, and film classrooms; and if the thousands of websites about it are anything to go by, Streetcar is as popular today as it was in 1947. Williams considered it his best play, and in 1999 the American Theater Critics Association agreed, voting Streetcar the best American play of all time.