Alex Kongsgaard tells Kelli White about his latest venture, The Alexes, a range of three Chardonnays that has already attained mythic status in Napa

Alex Kongsgaard builds surfboards, then he builds boats to carry those boards to the waves. Sometimes he creates these items from scratch. Other times, he attempts to make an existing vessel better.

On the day of our tasting, one such project was on display. Alex had lopped the backend off an old fiberglass boat and was working to extend it several feet. A grid of foam scaffolding was exposed. Nearby, a dozen kettle bells hunkered on the garage floor, recently used to tune the boat’s balance. “I needed it to be a bit more fierce,” he explains.

The younger Kongsgaard

Alex is the son of John Kongsgaard, a man of looming legend. He and his girlfriend (also named Alex) created the Alexes label in 2018, which is what I had come to taste. We arranged to meet in the venerable Judge vineyard, a pushed-up pile of rocks that produces some of the most singular Chardonnay in California.

The winery has been in the Kongsgaard family for generations. As a young man, John had planted it to Chardonnay upon the advice of André Tchelistcheff. It was an unusual recommendation for the time, but the gamble paid off. Today the wine sells for US$250 a bottle, and the line for an allocation is long.

For the past decade, Alex has been in charge of farming, and he seems both equally enthralled and vexed by the site. “In a good year, we get one and a quarter tons to the acre,” he tells me as we walk the rows, the California sun nagging the back of our necks. He points out the Eutypa skips, the widely varying vigor across the vineyard, the near total lack of standardization. In certain sections, vines appear to sprout from solid rock. “Mechanization is impossible here.”

One small patch of vines seems happier than the rest, with strong arms supporting thick, verdant canopies. Compared to the other vines, they seem almost vulgar. Alex explains that the soil had become depleted, so he reinvigorated it. “I took it too far,” he admits. “You have to do it really slow or you risk turning your vineyard into some other chump’s vineyard.”

Alex speaks like his father, who speaks like none other. Theirs is a proprietary family patois wherein classics professor meets surfer. Deeply philosophical musings on winemaking and grape growing are peppered with anachronistic dude-isms like “gnarly” and “bogus.” It’s charming and authentically Kongsgaardian.

Mythic wine

The Judge vineyard was not always Chardonnay, Alex explains; in a previous life it had been planted to Zinfandel along with Barbera and some Cabernet Sauvignon. “The Cabernet sucked here,” he pauses to kick at the ground. “And it’s a good lesson in what makes great Cabernet versus great Chardonnay. The soils are too extreme, the tannins were too hard and clipped. But Chardonnay likes to be unevenly ripe. We pick in one go to capture that.”

We make our way to an old tool shed, where Alex has stashed a large Yeti cooler. He pulls out three bottles, each a different lot of 2018 Chardonnay—the entire opening lineup of Alexes. Despite the fact that the wines are not being offered for sale, they have already become mythic in certain Napa circles, their existence whispered over at tastings and gatherings.

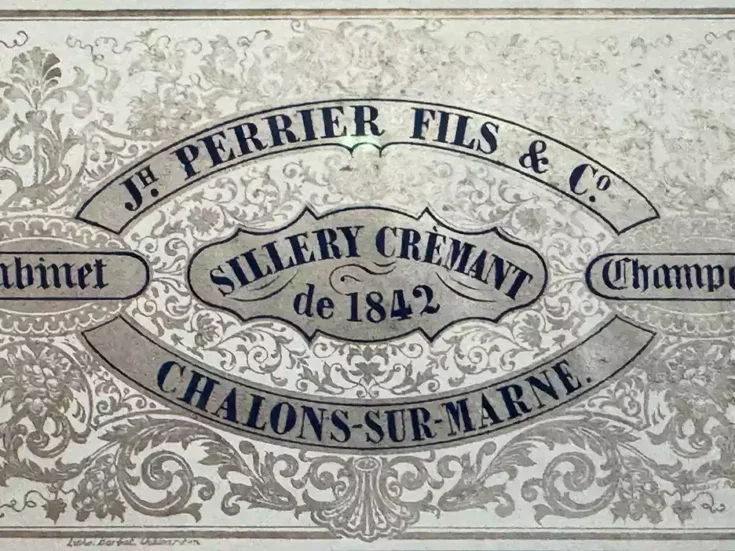

The sketches on the labels evoke boyhood preoccupations: robots, skeletons, sea creatures. But there is a deeper meaning, at least to Alex. He studied philosophy in college and is well-versed in the civilizations of antiquity. “I feel that the Greeks are the skeleton and Romans are definitely the robot,” he tosses off casually.

Alex, Alex², Alex³

The first wine, Primo Rorick (the sea horse), hails from a small block of own-rooted Chardonnay in the Rorick Heritage Vineyard where Alex Athens was once a partner. The second two were sourced from the Chuy vineyard in Sonoma—a 40-year-old patch of mountain Chardonnay the likes of which one rarely finds in California anymore. The vines, “big, old, and savage,” produced extraordinary fruit, but were ripped out shortly after the 2018 harvest. Alex shrugs. The vineyard “went the way of economics,” he says with resignation.

Alex divided his single ton of Chuy between two vessels—a four-year-old barrel and a clay amphora. And while all three wines were excellent, the amphora bottling was resplendent. Dense, tense, slightly hazy—the wine was both polished and wild. It was clearly Alex’s favorite as well. “I like the purity of this wine, unobstructed by the artifice of wood flavor.” He continues, “to me, this shows that amphora is not an inherently wacky thing to make wine in.” Nearly all of the amphora wines Alex has tried identified with the natural wine movement and were deliberately funky. By contrast, he refers to his wines as “unconventional but still reasonable.”

“These wines reflect the way I fantasize about twisting the dials at the Kongsgaard winery,” Alex confesses. But while certain elements of winemaking were changed (Alex harvested the fruit earlier and avoided new oak), the majority were kept constant—whole cluster press, super reductive conditions, extended natural fermentations, 20 months in barrel, and, of course, the grape.

A respected heritage

The results here at the Kongsgaard winery are some truly exciting Chardonnays that gesture lovingly back to Alex’s heritage rather than poking it in the eye. “I fantasized about starting my own business,” Alex reflects, “but the reality is that it is more important for me to work on the Kongsgaard stuff rather than start my own empire.”

“And besides,” he continues, “I come from this problematically rarified world of farming this unbelievable vineyard. Maybe the most fantastic, weird, rare vineyard in all of Napa.” We walk to the top of the slope. In one direction, the houses and vineyards of Coombsville splay; in the other, all of Napa Valley is revealed. Conversation turns to rootstock.

He has a lifetime of experimentation ahead of him, but the vineyard works. The Judge continues to yield preposterously majestic Chardonnay. Alex is just trying to make it work better.