Tim James follows “the tendrilled avenues of wine and the otherworld” in the poem “Grapes,” by DH Lawrence.

So many fruits come from roses

From the rose of all roses

From the unfolded rose

Rose of all the world.

Admit that apples and strawberries and peaches and pears

and blackberries

Are all Rosaceae,

Issue of the explicit rose,

The open-countenanced, skyward-smiling rose.

What then of the vine?

Oh, what of the tendrilled vine?

Ours is the universe of the unfolded rose,

The explicit,

The candid revelation.

But long ago, oh, long ago

Before the rose began to simper supreme,

Before the rose of all roses, rose of all the world, was even

in bud,

Before the glaciers were gathered up in a bunch out of the

unsettled seas and winds,

Or else before they had been let down again, in Noah’s

flood,

There was another world, a dusky, flowerless, tendrilled

world

And creatures webbed and marshy,

And on the margin, men soft-footed and pristine,

Still, and sensitive, and active,

Audile, tactile sensitiveness as of a tendril which

orientates and reaches out,

Reaching out and grasping by an instinct more delicate

than the moon’s as she feels for the tides.

Of which world, the vine was the invisible rose,

Before petals spread, before colour made its disturbance,

before eyes saw too much.

In a green, muddy, web-foot, unutterably songless world

The vine was rose of all roses.

There were no poppies or carnations,

Hardly a greenish lily, watery faint.

Green, dim, invisible flourishing of vines

Royally gesticulate.

Look now even now, how it keeps its power of invisibility!

Look how black, how blue-black, how globed in Egyptian

darkness

Dropping among his leaves, hangs the dark grape!

See him there, the swart, so palpably invisible:

Whom shall we ask about him?

The negro might know a little.

When the vine was rose, Gods were dark-skinned.

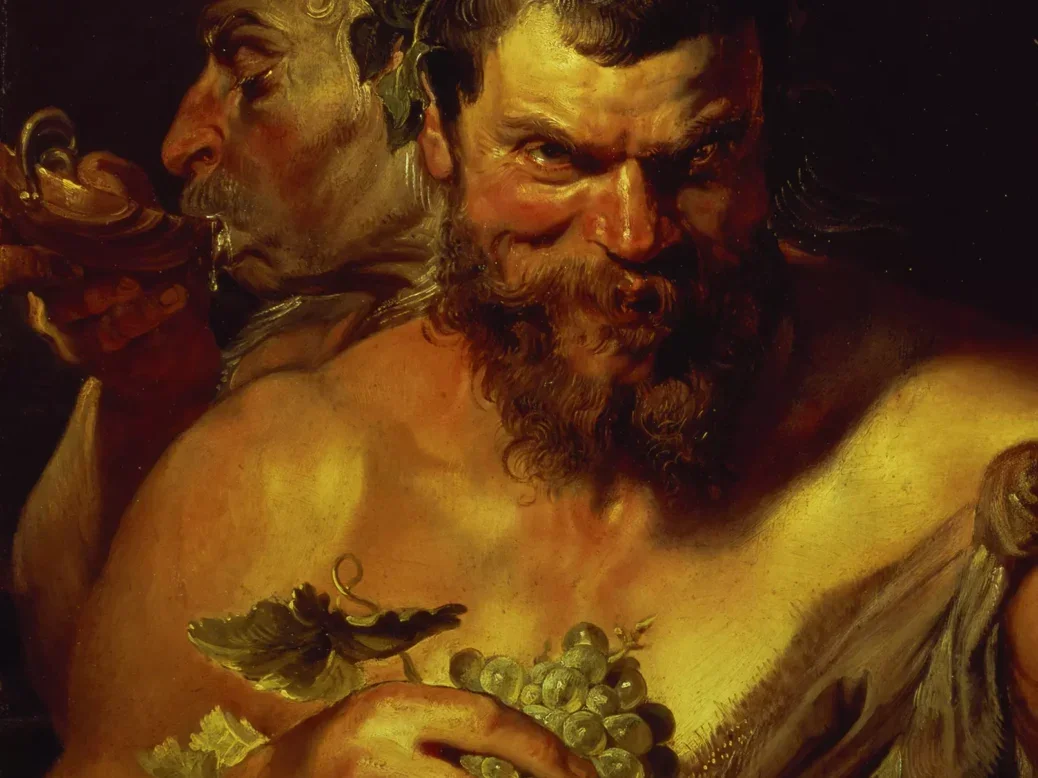

Bacchus is a dream’s dream.

Once God was all negroid, as now he is fair.

But it’s so long ago, the ancient Bushman has forgotten

more utterly than we, who have never known.

For we are on the brink of re-remembrance.

Which, I suppose, is why America has gone dry.

Our pale day is sinking into twilight,

And if we sip the wine, we find dreams coming upon us

Out of the imminent night.

Nay, we find ourselves crossing the fern-scented frontiers

Of the world before the floods, where man was dark and

evasive

And the tiny vine-flower rose of all roses, perfumed,

And all in naked communion communicating as now our

clothed vision can never communicate.

Vistas, down dark avenues

As we sip the wine.

The grape is swart, the avenues dusky and tendrilled,

subtly prehensile.

But we, as we start awake, clutch at our vistas democratic,

boulevards, tram-cars, policemen.

Give us our own back

Let us go to the soda-fountain, to get sober.

Soberness, sobriety.

It is like the agonised perverseness of a child heavy with

sleep, yet fighting, fighting to keep awake;

Soberness, sobriety, with heavy eyes propped open.

Dusky are the avenues of wine,

And we must cross the frontiers, though we will not,

Of the lost, fern-scented world:

Take the fern-seed on our lips,

Close the eyes, and go

Down the tendrilled avenues of wine and the otherworld.

***

Irritatingly, I can’t read this poem so full of roses and wine and dreams without some famous lines from another poem rising like an earworm:

They are not long, the days of wine and roses:

Out of a misty dream

Our path emerges for awhile, then closes

Within a dream.

That’s the second stanza; the first makes the same, hardly profound point with different words. And there’s another sticky bit of rose-and-remembrance stuff by the same poet, Ernest Dowson (writing in the decadent 1890s), recalling how he had “Flung roses, roses riotously with the throng” before he became “desolate and sick of an old passion.”

“Divine decadence, darling!” as Liza Minnelli’s campy Sally Bowles remarked in Cabaret, flicking her glittering fingernails as Nazi fascism proliferated around her. Some, however, might find Dowson overly sentimental and a touch trite. How much better, surely, the toughness and vitality (however imprecise) of DH Lawrence’s invocation of an earthy truthfulness of body and spirit, of dark, instinctual life—one way to which, it seems, is an intoxication with poetic loveliness and perhaps with wine. Lawrence’s dreams are not the misty ones out of which tragically brief human happiness emerges; rather, they speak a repressed, creative, and mysterious truth:

And if we sip the wine, we find dreams coming upon us

Out of the imminent night.

As to roses (mentioned more than vines or grapes in Lawrence’s poem), there can’t be many poems that are as hostile to them as this one. Lawrence acknowledges the rose’s cultural reign, the beauty of its spread petals and colorfulness, the glories of the fruits in the Rosaceae family. He sees the rose “simper” in its supremacy. But it is too obvious, too cheerfully “skyward-smiling” and “explicit.” The rose world is associated with that of modern human life as invoked later in the poem, the “vistas democratic, boulevards, tram-cars, policemen,” a world whose sobriety is symbolized by the soda-fountain. For our mundane world is the one in which, tellingly, “America has gone dry.”

Surrendering to a sensual world

The poems collected in Lawrence’s Birds, Beasts and Flowers, including “Grapes” (and “Pomegranate,” “Peach,” “Fig,” and “Medlars and Sorb-Apples”), were, the poet said, “begun in Tuscany, in the autumn of 1920, and finished in New Mexico in 1923, in my thirty-eighth year.” That initial year was also when America “went dry,” as national Prohibition came into force. But a pervasive, less literal dryness also comes from the human intellect and human institutions in a post-diluvian world.

Lawrence seems to have been a temperate drinker—his father had abused alcohol, and Lawrence explicitly showed a lack of sympathy for drinkers or drug-takers in his novel Sons and Lovers. His many visits to Italy inevitably included a close relationship with wine, of course. Ian d’Agata, in his magisterial Native Wine Grapes of Italy, mentions that the obscure white grape Maturano (or Motulano) made a wine that was a favorite of Lawrence’s. And there are letters about the grape harvest there. On a later visit to Tuscany, Lawrence wrote, “They finished bringing in the grapes on Wednesday, and all the house smells sourish from the great vats where they’re waiting to be squashed. We’ve got festoons of grape hung up everywhere […].” Incidentally, Lawrence was not always lyrical about the vinified fruit of the vine; he once described a Spanish wine as “foul […] the sulphurous urination of some aged horse.”

This poem is much less about wine than about grapes and, especially, “the tendrilled vine.” Before the rose in all its explicitness emerged, when “There were no poppies or carnations,” there was a “dusky, flowerless, tendrilled world,” with ferns and vines. Back then, when all was green, dim, and secret, “before eyes saw too much,” and “where man was dark and evasive,” “the vine was the invisible rose.”

To return there means to make some surrender to an instinctive, sensual world on the verge of which society, Lawrence suggests, is hesitating, like a child resisting sleep—and therefore resisting dreams—with “agonised perverseness,” though desperately in need of it. To get to the other world means denying the sober legislators and its policemen of sobriety. Perhaps in this context, the implicit Christian symbolism of the rose, the rose of all roses, is relevant. Lawrence had rejected Christianity and its moral strictures and structures as another barrier to the infinity of the night—though he did call himself “a passionately religious man.”

Resisting the soda-fountain?

And what of wine, the expression of those dark grapes hanging “invisibly,” “Dropping among his leaves”? It stands for resistance to dry America’s sober soda-fountain, giving vistas down dusky avenues that soda doesn’t encourage. But to me (though one could easily argue the opposite on the basis of this poem alone), this is not a concrete suggestion that alcoholic drunkenness will reveal fundamental truth, as a later generation was to argue with regard to the effects of psychedelic drugs. Lawrence is not a proto Timothy Leary, though there’s something in the comparison, including Leary’s injunction to “think for yourself and question authority.”

It is perhaps more metaphoric than real, this congeries of vines, grapes, and wine, symbolizing the necessary transformatory social imagination to take us on a Lawrentian journey of sensuality and spirituality. But for the wine lover who welcomes the inebriatory qualities of wine, as well as other sensual ones (and has perhaps even been stimulated by it to perceive the infinite), it has to be a particularly powerful metaphor.

Take it as metaphor or prescription. Even if we are as perversely reluctant as the tired child, says Lawrence, we must sip the wine and follow the dark avenues across the frontiers, to find the dreams offered by the “imminent night.” We must

Close the eyes, and go

Down the tendrilled avenues of wine and the otherworld.