As the Bhutan Wine Company releases its first wines—the first ever made in the Himalayan country—Chris Howard reports on how a remarkable project came to be, and what it promises for the future of wine and sustainability.

“This mood makes itself felt everywhere, politically, socially, and philosophically. We are living in what the Greeks called the καιρóς (kairos) – the right time – for a ‘metamorphosis of the gods,’ i.e. of the fundamental principles and symbols.”—C. G. Jung, Present and Future (1958)

Beyond the familiar terrain of fine wine, a new horizon is emerging in the most unexpected of places: the Kingdom of Bhutan. The Himalayan nation, renowned for its Gross National Happiness policy and pristine environment, has embarked on a journey that challenges traditional understandings of the wine world.

The inaugural release of the Bhutan Wine Company’s first wines this October not only marks a significant milestone in the global history of wine, but further disrupts the Old World/New World binary. Much more than the launch of a new brand, Bhutan’s emergence as a wine country serves as a catalyst for reimagining wine’s narrative identity in the high era of globalization and climate change.

This article will explore the unique terroir of Bhutan, trace the serendipitous origins of its wine industry, and examine the challenges and opportunities of cultivating both vines and a wine culture in this Buddhist kingdom. Although it’s too early to judge the wines themselves, if we accept Hugh Johnson’s definition of fine wine as “wine worth talking about,” Bhutan has already earned its place in the conversation.

Land of the Thunder Dragon

While the map is not the territory, let’s get our bearings. Situated in the Eastern Himalayas between China and India, Bhutan is a small, landlocked kingdom of approximately 38,000km2 (14,700m2 ) slightly smaller than Switzerland. Known locally as “Druk Yul” or “Land of the Thunder Dragon,” for the mythical legend of fire-breathing dragons descending from the snow-capped peaks, Bhutan is celebrated for its dramatic landscapes, which range from subtropical plains to steep mountains and deep valleys.

The country’s geography is defined by the Himalayas, which sculpt distinct climate zones that vary with altitude—from subtropical in the south to temperate highlands and polar-like conditions in the north. The country’s isolation, with no roads leading outside the Kingdom until the 1960s and air access arriving only a few decades ago, has allowed Bhutan to preserve its unique lifeworld while engaging with globalization on its own terms.

Bhutan stands apart not only for its natural beauty but also for its distinctive cultural and political landscape. The world’s only Vajrayana Buddhist nation, its culture is deeply rooted in this form of Buddhism, which emphasizes tantric rituals, visualization, and practices designed to provide a faster path to enlightenment. This spiritual foundation permeates Bhutanese society, influencing everything from daily life to national policy.

Politically, Bhutan transitioned from an absolute to a constitutional monarchy in 2008, with its government organized around the principles of Gross National Happiness (GNH). GNH is not a slogan or a simple measure of subjective wellbeing but a comprehensive policy framework that guides all government decision-making. If an initiative doesn’t bring happiness, Bhutan doesn’t do it.

The GNH policy encompasses nine domains: psychological well being, health, education, time use, cultural diversity and resilience, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity and resilience, and living standards. This holistic approach ensures that development and policy decisions consider their impact on the overall wellbeing of the population and the environment. Hence, the decision to enter the wine world was not taken lightly.

Bhutan’s commitment to environmental conservation is exemplified by its status as the world’s first and thus far only carbon-negative country. This remarkable achievement is the result of several factors and initiatives. Bhutan’s constitution mandates that at least 60% of the country remain under forest cover in perpetuity; currently, forests cover approximately 71% of the land.

The country generates clean hydroelectric power, much of which is exported to neighboring India, offsetting millions of tons of annual carbon dioxide emissions. Additionally, Bhutan has banned export logging and is transitioning to become the world’s first fully organic nation. These forward-thinking practices have simultaneously erased Bhutan’s carbon footprint while increasing its biodiversity.

With approximately 95% of its population (just shy of 800,000) practicing traditional farming, Bhutan maintains a deep connection to the land. While the Bhutanese are world-renowned farmers, the country’s geographic isolation and lack of connection to the ancient Silk Road trade routes meant the first grape vines were planted only in 2019.

Vision and serendipity: The birth of a wine country

How did Bhutan, with no prior viticultural history, suddenly emerge on the wine scene? The Bhutan Wine Company was founded through a visionary collaboration between the Kingdom of Bhutan and American entrepreneurs Michael Juergens and Ann Cross.

The project’s roots lie in Cross’s long-standing fascination with Bhutan, which led the couple to visit in 2017. Juergens, a wine business consultant and Master of Wine candidate, immediately recognized the country’s untapped viticultural potential.

During a dinner with government officials, Juergens’ facetious inquiry about the absence of Bhutan’s vineyards sparked a chain of events leading to the company’s establishment. Returning to the US, Juergens drafted a white paper proposing a high-value, low-volume wine industry aligned with Bhutan’s GNH framework.

Initially met with radio silence, on a subsequent visit Juergens found enthusiasm for his proposal had grown. When asked if he truly believed in Bhutan’s potential as a wine region, he affirmed, “Absolutely, from the bottom of my heart, I believe this place could be the next great wine region in the world for the next 500 to a thousand years.”

The Bhutanese government eventually invited Juergens to spearhead the initiative himself, a proposition he hadn’t foreseen but eagerly accepted. In Bhutan, foreign companies are required to partner with local citizens, so the Bhutan Wine Company appointed Karma Choeda, a former diplomat as its Chief Operating Officer, and Pema Wangchuk as vineyard manager.

Reflecting on the serendipitous venture, Juergens muses, “Anyone could start a winery, but to do this, which is completely crazy, was more interesting.” This spirit of adventure, combined with a fortuitous alignment of interests, has set the stage for what may become one of the world’s most intriguing wine regions.

The heights of terroir

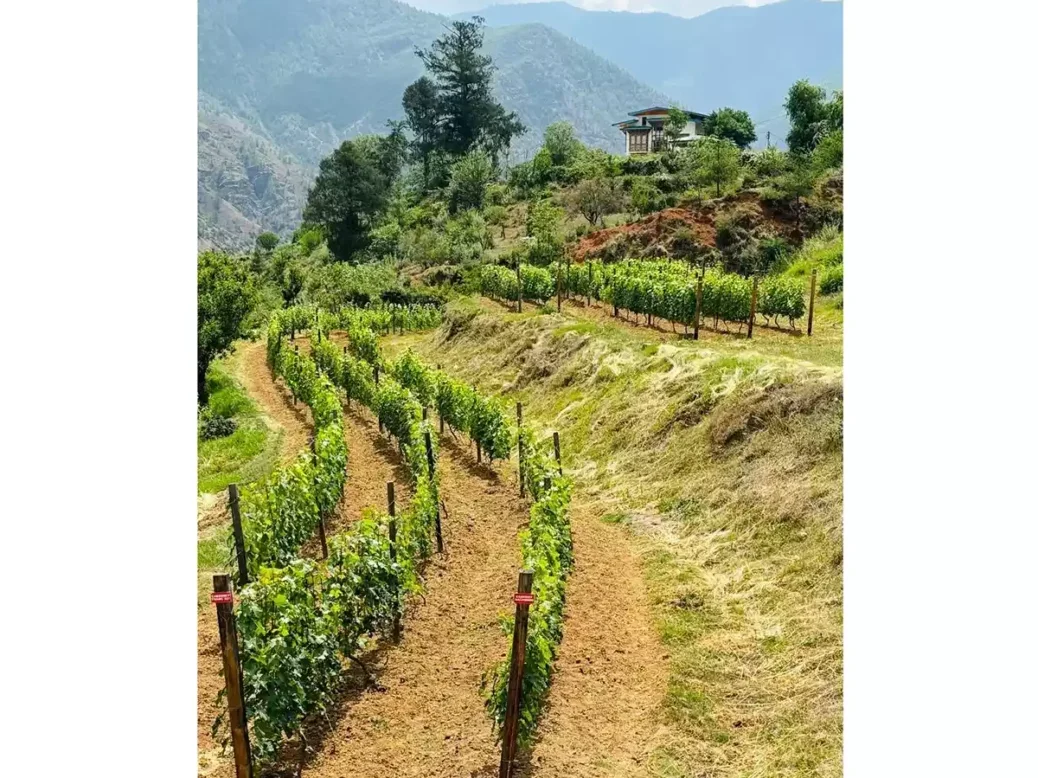

What of the terroir, that certain “somewhereness” we always seek in wine? In Bhutan, this quest unfolds across a dramatic landscape, with vineyards stretching from 150–2,700m (490–8,900ft) above sea level. This altitude variation creates a mandala of microclimates and growing conditions, each imparting unique characteristics to the grapes. The soil composition adds another layer of complexity, ranging from alluvial sands in river valleys to rich red clay and loam on hillsides.

With no historical precedent for Vitis vinifera cultivation, Bhutan’s viticultural journey embodies a pioneering spirit marked by experimentation and adaptation. Sixteen grape varieties are currently under trial across nine sites covering approximately 80ha (200 acres). The reds include Syrah, Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Malbec, Sangiovese, and Tempranillo. The whites comprise Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Petit Manseng, Riesling, Chenin Blanc, Vidal, and Traminette. The strategy involves planting multiple varieties in each vineyard and scaling those that thrive.

The diverse terroir and altitude variations create an extended growing season, with harvests spanning from June to October. In the subtropical south, a unique approach involves winter cultivation and early spring harvests, sidestepping the summer monsoon. This stretches the company’s wine production over eight to ten months, a significant advantage over traditional wine regions constrained by shorter harvest windows.

Bhutan’s pristine environment is integral to its terroir. The country’s ecological orientation ensures pure water sources, minimal pollution, and high biodiversity. In the face of anthropogenic climate change, Bhutan’s high-altitude terroir offers some natural advantages. As rising temperatures threaten many traditional wine regions, Bhutan’s mountainscapes are a mitigating influence. The cooler temperatures at higher elevations allow for extended ripening periods, resulting in wines with concentrated aromas, higher acidity, and enhanced polyphenols. These conditions yield wines that are naturally lower in alcohol and tend to deliver more concentrated flavors due to smaller berries with thicker skins. The high-altitude environment also reduces disease pressure, naturally aligning Bhutan’s commitment to organic farming.

While high-altitude viticulture has proven successful in regions such as Alto Adige, Italy, and Uco Valley, Argentina, Bhutan’s elevations push these boundaries even further. As the roof of the world, the Himalayas represent the ultimate high-altitude frontier. Bhutan’s venture into winegrowing not only promises unique wines but also offers a glimpse into the future of climate-resilient viticulture. Bhutan may offer a blank canvas, but pioneering any entirely new wine frontier is not without challenges.

Cobras in the vineyard

Training vineyard and winery workers with no prior viticultural experience presents a significant hurdle. For example, it’s taking time to instill the counterintuitive practice of reducing grape yields to enhance wine quality, which goes against local inclinations to maximize crop yields. The company’s Californian winemaker, Matt Brain, notes that such challenges are quickly being surmounted by the “intelligence, passion, and work ethic” of the Bhutanese people involved. Other challenges include supply-chain issues, since winery equipment and supplies are not readily available as they would be in established wine regions.

Perhaps the most unique challenge has been wildlife. “We’re not worried about traditional vineyard diseases, like red blotch or phylloxera,” says Juergens, “but we are worried about monkeys and cobras!” Along with king cobras, Bhutan is home to several species of vipers and kraits that have been found in the vineyards. Hence, anti-venom protocols are a key aspect of health and safety. Tigers, Asian elephants, and leopards are other potential threats, none of which are addressed in viticulture textbooks. In light of Bhutan’s Buddhist philosophy of ahimsa, or “do no harm,” and its celebration of biodiversity, innovative solutions are needed. Electric fences can help deter some animals, but what about mountainside vineyards that are way off grid?

Cultivating a wine culture from the ground up

Cultivating a wine culture, like the terroir itself, takes time. The Bhutanese have long enjoyed ara, a traditional fermented beverage made from rice, buckwheat, or barley, which serves as a bridge to wine appreciation. Many Bhutanese encounter wine while studying abroad, fueling local interest in the homegrown initiative. To nurture this budding wine culture, Karma Choeda and his team, after intensive training at 67 Pall Mall in Singapore, have opened a wine bar in the capital, Thimphu, which also serves as an education space.

For Bhutan, the wine industry is about more than a new product; it’s a source of national pride and identity. As Choeda explains, “Being able to grow grapes and produce wine in Bhutan will make the Bhutanese people very proud indeed, capturing and promoting our essence and identity in a bottle.”

From wine worlds to wine as worlding

As Bhutan’s nascent wine journey unfolds, it offers a worldmaking narrative that blends tradition with innovation, spirituality with entrepreneurship, and local identity with cosmopolitanism. The challenges are formidable—from training a workforce in viticulture to navigating the complexities of high-altitude viticulture and coexisting harmoniously with leopards and cobras. Yet, the potential rewards are even more promising. Bhutan’s approach to winegrowing, grounded firmly in its principles of Gross National Happiness and environmental stewardship, could serve as a model for sustainable viticulture in the face of climate change.

Bhutan’s entry into the wine world represents more than just a new dot on the global wine map. It symbolizes a broader shift in how we perceive and value wine regions, challenging established norms and expanding the boundaries of what’s possible in viticulture. As the first bottles of Bhutanese wine make their way into the world, they carry with them not just the untouched flavors and textures of Himalayan terroir, but also the story of a quietly wise country’s bold vision and the promise of new perspectives and experiences in the world of wine. Bhutan’s wine venture seems a poignant expression of the zeitgeist and the necessary metamorphosis—a fundamental transformation in our relationship to the cycles and delicate interdependencies of earthly co-existence.