In our current neo-prohibitionist moment, it’s hard to imagine governments organizing to promote wine consumption. And yet, that’s precisely what happened with the Drink More Wine campaign in France 90 years ago, says Rod Phillips.

Today, when wine consumption is declining in many countries and when public health authorities are issuing warnings about the risks associated with alcohol consumption, it seems inconceivable that there was a time when authorities encouraged people to drink more wine. Yet in France in the early 1930s, the wine industry, the government, and prominent physicians did just that. What we might call the Drink More Wine campaign is one of the strangest episodes in the history of French wine.

There was, of course, a specific context. During the 1920s and 1930s, French wine producers had trouble selling their wine at home and abroad because markets had either shrunk significantly or disappeared almost completely. World War I had killed millions of men—men of the prime wine-drinking demographic—and France had suffered the greatest losses by population of any major nation. Of males born in 1894, men who were 19 or 20 when the war broke out and 23 or 24, when it ended—one third died in combat.

You have only to look at the lists of names inscribed on war memorials in villages throughout France to see the scale of losses in this and other cohorts. France’s population fell from 41.6 million in 1914, to 38.7 million in 1918—a loss of about 7% of the total population but of more than 30% of men aged 18 to 35. And it did not reach the prewar size again until the end of the 1930s.

The loss of so many men had long-term implications for France’s economy and population growth, but for present purposes the significant thing is that they were in important wine-consuming age groups. Even so, overall wine consumption in France remained stable in the immediate postwar period thanks to an increase in per capita consumption among the diminished wine-drinking population; it rose from just over 100 liters in the years before the war, to almost 120 liters in the years following it.

That, however, was wine consumption for every person in France—children, as well as women and men. Annual wine consumption among adults was often higher than 200 liters (more than half a liter a day), and among adult men, who drink more than women, it was even higher. The domestic market was absorbing a lot of French wine, then. But all things being equal, it would have absorbed far more were it not for the loss of more than a million wine-drinking men during the war.

France’s major export markets were in even worse shape. In the United States, National Prohibition (1920–33) was in force throughout the decade, and French wine imports stopped entirely, though small volumes of the most prestigious and expensive wines were smuggled in. In Britain, a top market for French wine, higher taxes were imposed on imported wine in the 1920s, and increased prices depressed demand. Germany suffered a monetary collapse in 1923 that ruined many middle-class, wine-drinking families. In Russia, the Revolution of 1917 destroyed the demand of the imperial court, the nobility, and the well-off bourgeoisie for luxury French wines, especially Champagne.

These conditions led to a growing surplus of French wine during the 1920s, estimated to be about 6 billion liters by 1930. It might not all have been the result of market challenges, however. Jules Alquier, the secretary general of the Scientific Society of Food Hygiene, argued in 1930 that producers in some regions were partly responsible for the surplus by heavily irrigating their vines just before harvest, thereby increasing the volume of juice by three or four times.

If the 1920s were tough for French wine, the Great Depression, triggered by the stock market crash in 1929, reduced sales of French wine even more by restricting consumer spending. The depression struck countries at different times and had varying effects. In the United States, the depression was still deep when Prohibition ended in 1933, and imports of French wines during the rest of the 1930s were far lower than they had been before Prohibition began. The depression affected France a couple of years later than more industrialized countries, and the French government mitigated its effects on unemployment by expelling the foreign workers who had been recruited to make up for labor losses as a result of the war. But in most countries that had been important markets for French wine, high unemployment and financial turmoil reduced spending on consumer goods such as imported wine.

All that was needed to turn these challenges facing French wine producers into a crisis was a bumper harvest of grapes—and that was what France’s vineyards delivered in the early 1930s. From 1930 to 1933, France produced an annual average of 52 million hectoliters of wine, but in 1934 it produced 78 million, followed by 76 million hectoliters in 1935, —more than 50% up on the preceding years.

If these huge harvests were not bad enough, Algeria also recorded increased production in those years. From 1930 to 1933, average production of wine in Algeria had been 16 million hl, but the 1934 harvest produced 22 million hl, and the 1935 harvest, 19 million. The additional wine added to the surplus from metropolitan France, because almost all Algerian wine was routinely blended into the then-anemic wines of Languedoc to give them color, body, and alcoholic strength.

If there was a lake of surplus French wine by 1930, there was a good-sized sea of it by 1935. A circular from the Nicolas chain of wine stores informed its customers that the 1934 vintage was not of great quality and that the weak wines it produced got weaker by the day. “This is what excessive production gives us. And the market is positively flooded with it, at prices that challenge those of mineral water.” But even at low prices, the wine was not selling, and because the great bulk of it was not of a quality that would age, it had to be sold and consumed quickly.

A barrel of wine per head

Whatever its causes, the wine surplus was certainly serious enough for the French government to take action as early as 1931. It figured that the situation was a long-term problem, not merely a short-term blip; in 1931, there was no reason to believe that Americans would abandon Prohibition soon, that a czar and a Champagne-guzzling court would be restored, or that the economic depression would soon end. The French government adopted policies to reduce wine production; the planting of new vineyards was restricted, high-yielding vineyards (this was before AOC rules limited yields) were taxed, and provisions were made for the compulsory distillation of excess wine.

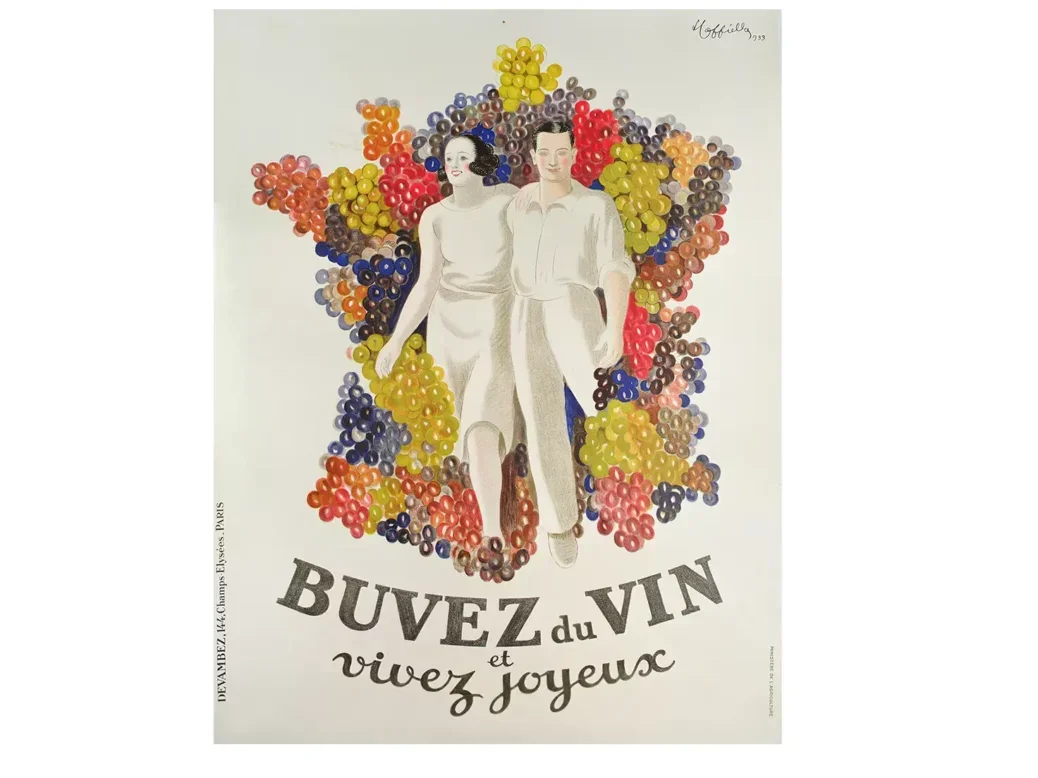

Attacking overproduction had historical precedents in France, but the government’s other means of dealing with the problem—attacking underconsumption—did not. The Comité de Propagande du Vin (Committee to Promote Wine) was established in December 1931, its mandate being to explore ways of increasing wine consumption by exploiting the most modern methods of advertising and new mass media, such as radio and film.

But how to do that, at a time when markets in France and elsewhere were contracting even more? The answer was to encourage the French, who were already drinking wine at arguably the highest level in the world, to drink yet more. It seemed the only way to reduce the excess wine that every vintage produced and to which 1934 and 1935 had added so much more. This was one of the strangest episodes in the history of French wine. Although the French enjoyed a high level of wine consumption in the early 1930s, and although wine was considered beneficial to health, French citizens had never before had to be urged en masse to drink even more wine.

The Drink More Wine campaign built on an established belief that wine was a healthy beverage, but it added the argument that if drinking wine was good for you, drinking more wine was even better for you. In 1930, even before the wine glut reached critical proportions, Jules Alquier—who, as we have seen, had blamed the role of irrigation in creating the wine glut—noted that, though the doubling of wine consumption in France during the previous hundred years sounded like good news, the French were still not consuming all the wine available, and he called for every citizen to drink a barrel of wine.

We should probably not place too much literal weight on statements such as this. A barrel might mean a 225-liter barrique, a 600-liter demi-muid, or anything else in between. French adults were already each drinking the equivalent of about a Bordeaux barrique of wine a year, and it seems inconceivable that Alquier was suggesting that they double their intake to a 456-liter Burgundian queue. It is probably better to think of his proposal in rhetorical rather than literal terms.

Expressions of alarm that wine consumption was not rising quickly enough became even more urgent as the wine glut ballooned. In 1934, agronomist Raymond Brunet noted that between 1910 and 1924, the consumption of coffee in France had risen by 46%, and that of tea by 147%, while consumption of wine rose by a mere 24%. “Therein,” he wrote, “lies a veritable national danger.”

Medical support for a patriotic duty

The ground was ready for the full-throated Drink More Wine campaign that was launched when France’s wine surplus ballooned in the early 1930s. In France, annual per capita consumption stabilized at about 118 liters from the mid-

1920s, but that certainly wasn’t going to clear the backlog of wine. A series of proposals was advanced to convince French wine drinkers to imbibe even more, many of which were likely to have been just as futile as proposals being made today to encourage wine drinking. Some in the 1930s were aimed at children, others at non-drinkers, while most targeted regular drinkers who, it was thought, could most easily be persuaded to increase their contribution to the cause.

The French medical profession, historically a stalwart of wine consumption, of course joined in enthusiastically. Eminent doctors formed an association called Médecins Amis du Vin (Physician Friends of Wine), which wrote letters to newspaper editors and published articles in favor of wine. The association also held conferences funded by the government-sponsored Comité de Propagande du Vin. One conference, held in Beziers in 1934, included papers presented by physicians under titles such as “Wine in the Infant’s Diet,” “Wine in Pediatric Medicine,” “The Use of Wine for Women in Labor,” and “Wine as a Tonic for the Elderly.”

Wine, then, was a healthy beverage from the start of life to its end. And if that were not argument enough in favor of wine, wine could also apparently lengthen one’s life. An advertisement in a book of French highway maps advised motorists to eat at restaurants where wine was included in the price of a meal, and helpfully noted that the average life expectancy of a wine drinker was 65 years, compared to 59 years for a water drinker, and that 87% of France’s 100-year-old citizens were wine drinkers.

Added to these claims was the message that wine, which had been declared France’s national beverage at the turn of the century, was rooted in French soil. This unusual appeal to terroir meant that drinking wine was not only a healthy pleasure but also a patriotic duty. Indeed, one doctor linked wine to the very existence of France: “For over a thousand years, wine has been the national drink of the French, and although they have been surrounded by enemies against whom they have fought more wars than any other people, the French have not only survived but they are among the two or three most important nations in the world.”

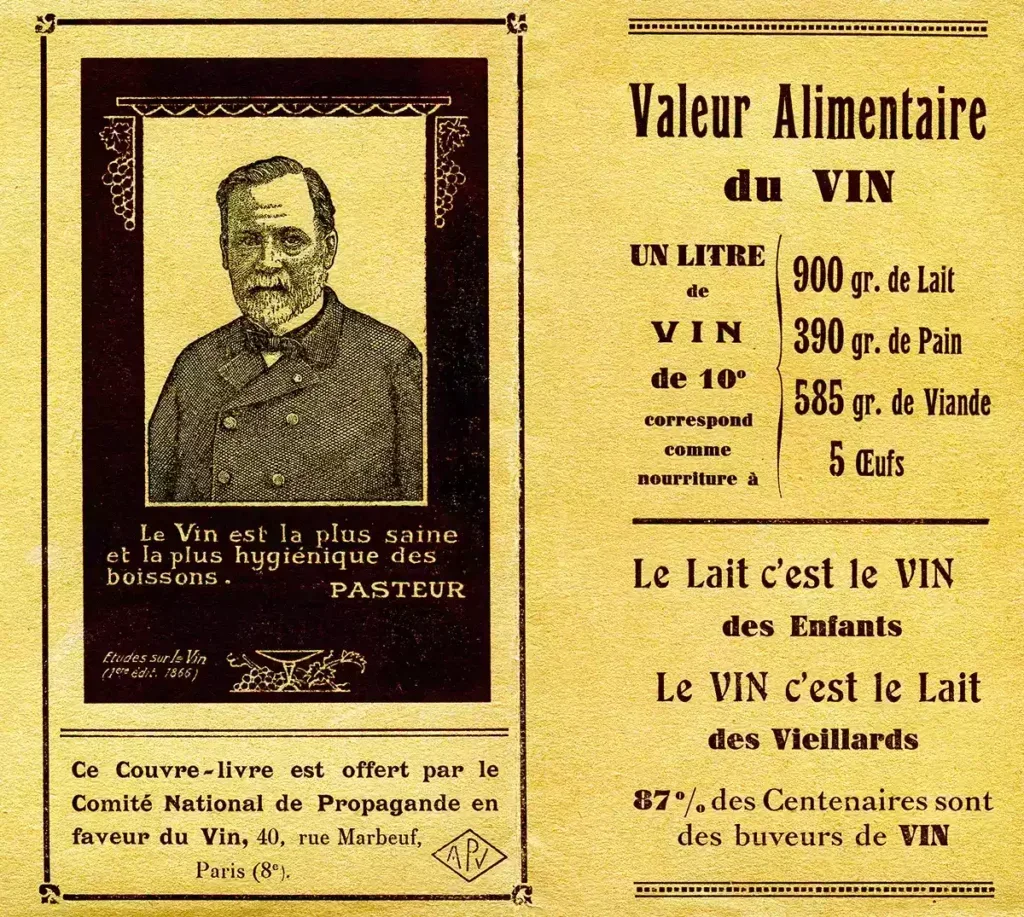

The French post office joined in on the act, employing a cancelation mark that read, “Wine is a food. Drink wine” and issuing Cinderella stamps (used for advertising, not postage). One carried a portrait of Louis Pasteur, with his famous saying, “Wine is the healthiest and most hygienic of beverages,” while another showed a map of France with a line demarcating the northern extent of viticulture and indicating high rates of alcoholism and tuberculosis above the line. This stamp bore the messages “Alcoholism is held in check by the consumption of wine” and “In regions where wine is consumed, tuberculosis is less common than in others.”

All manner of media was exploited to carry the message that French citizens should drink more wine: posters, billboards, newspapers, and new outlets such as radio, movies, and neon signs. The committee encouraged movie directors to include wine positively in their films, and hundreds of neon signs were erected in Paris, with messages that included “A meal without wine is like a day without sunshine,” a dictum borrowed from Brillat-Savarin. Between 1934 and 1937, Radio Paris broadcast a series of talks on the history of France through wine. Listeners learned that Louis XVI failed as a king and brought on the French Revolution because he diluted his wine with water, which prevented him from thinking deeply enough. But the great ideas of the Enlightenment, of course, came forth because the philosophers drank wine liberally.

If wine was beneficial for the elite brain, it was also brilliant for the elite body. It was proposed that cyclists in the Tour de France should drink wine and brandish the bottles so as to associate wine and physical performance. The French Olympic Committee got on board the wine campaign and asked that French athletes at the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles—where Prohibition was still in force—“be given the same consideration as French sailors in American ports. That is to say, that they be accorded a free daily allowance of a liter of wine.” The team had French chefs, the committee noted, “but without wine, the food will not be the same.”

The medical messaging apart, much of the campaign—urging people to include wine with their meals, for example—was unobjectionable. But the continuation of the wine ration provided to French soldiers that had become important during World War I—there had been no regular ration in France’s prewar army—was attacked by temperance campaigners because it introduced young men who were non-drinkers to alcohol.

Even more problematic were proposed policies that targeted children and young adults. As we have seen, there was a current of thinking in France’s medical profession that wine had a place in infancy, and ideas circulated about gradually introducing children to wine so as to ensure they were hearty wine drinkers as adults. Proposals to provide children with diluted wine with their lunch were easily swept aside, but wine was integrated into school lessons. When children took dictation, they copied Louis Pasteur’s writings on the health benefits of wine. Geography lessons included learning the location of France’s wine regions. Meanwhile, mathematics classes included equations such as “One liter of wine at 10 degrees corresponds as a food to 900 grams of milk, 370 grams of bread, 585 grams of meat, and five eggs.”

If any people within the control of France seemed beyond the call to drink more wine, it was the mostly non-drinking Muslims who lived in France’s colonies in North Africa. But they, too, could help with the wine glut by eating wine grapes as fresh fruit and by drinking grape juice. A conference was held in Tunis in 1936 to address issues of making and conserving grape juice.

But the force of the campaign was directed at metropolitan France and at men and women who were already wine consumers. Restaurants were encouraged to price wine fairly and to include it in the price of meals. More retail outlets were permitted: By 1931, the number of bars serving wine was back to the prewar level of 480,000, and by 1935 there were 508,000.

Drink More Wine: Lessons for today?

Did wine consumption in France rise? Not at all, as far as we can tell. Average annual per capita consumption of wine from 1925 to 1930, before the campaign got under way, was 119 liters. Throughout the 1930s (1931–38), it averaged a remarkably stable 118 liters. The French continued to enjoy wine, but they were resistant to increasing their consumption, or given the hard economic conditions of the 1930s, they were unable to.

Does this episode in the history of French wine hold any lessons for the present? Not really. The aim then was to increase the wine consumption of a population that was already drinking a lot of wine. The aim of some bodies today is to stop the decline of wine consumption from relatively low to even lower levels. More important, wine is consumed within a complex context that includes the flexibility of budgets, beliefs about health, the cultural value of wine, the sociability associated with wine, and the availability of alternative sources of alcohol and other stimulants. Simply urging people to alter one aspect of their behavior, as if it existed in isolation, is futile.

Many of the current suggestions for increasing or stabilizing wine consumption—using TikTok, designating months for drinking wine with friends, getting celebrities to endorse wine—smack of the desperation of many proposals in France in the 1930s. To be sure, no one today is suggesting that wine should be included in school meals, but there are people who would love Taylor Swift to pull out a bottle of Chardonnay during her concerts.