As Howell Mountain enters its fifth decade as an appellation, the reputation of Randy Dunn and his powerful Cabernet Sauvignons remains a convenient touchstone for the wine trade. But as Roger Morris reports, this Napa Valley mountain is now the province of a new guard of well-financed, market-savvy producers making sophisticated, highly rated red wines. Nevertheless, don’t expect gentrification of this still-untamed region anytime soon.

The interview has now shifted from the hillside tunnel that serves as barrel cellar for Dunn Vineyards—a somewhat damp venue that fits the mood of this rainy spring morning on Howell Mountain—into the winery office, which feels more like a rural farmhouse kitchen than a business venue. In fact, the old but sturdy structure was once a residence and, before that, a 19th-century stagecoach stop between Pope Valley and Napa Valley.

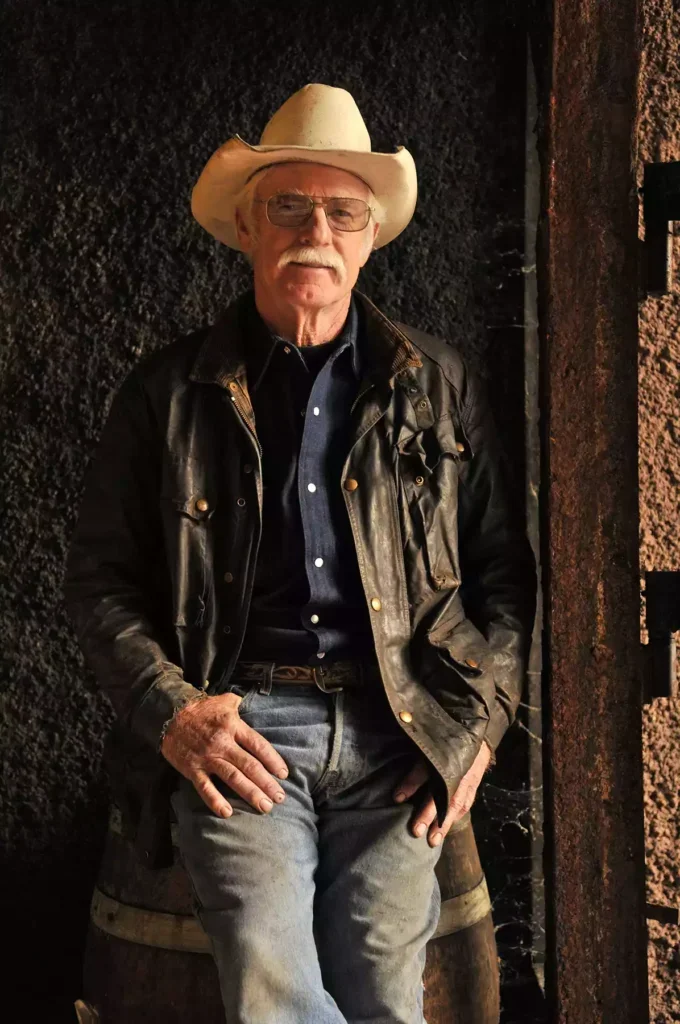

By this point in the conversation, Mike Dunn, primary winemaker at Dunn for the past 20 or so years, has taken me through the winery’s origin story—how his stepfather, Randy Dunn, established the reputation of Howell Mountain wines during the 1980s with his tannic-but-delicious, kick-ass Cabernet Sauvignons. Mike paints his own role as that of the dutiful yet irreverent stepson who makes most day-to-day decisions, though sometimes only after considerable arguments with his stepfather. Those who have worked with Randy Dunn know that he often has strong opinions—for example, insisting on keeping his big, burly wines under 14% ABV, even if it means physically stripping them of any excess.

In fact, the elder Dunn has stubbornly insisted that all of Napa Valley should lower its alcohol levels, publishing in the summer of 2007 a testy open letter that offended quite a few people in the wine trade. “Influential members of the wine press have led the score-chasing winemakers/owners up the alcohol curve,” he wrote, “and now I hope that it soon will lead them down.”

Mike has also elaborated on Randy’s role in founding Howell Mountain AVA (now in its 40th year), on the problems Dunn winery had with a Brettanomyces infestation in the early 2000s (“We had stopped sterile filtration, for one thing”), and on Randy’s various quarrels with the wine establishment. On cue, Dunn quietly saunters in—there is no other description—from outside. He is a smallish man, his drooping mustache now a snowy white, but at almost 80 he still exudes an aura of quiet vigor.

He gives a deferential nod and a sly smile in my direction and pulls up a chair off to the side, as if not to interrupt the conversation. The relationship between Dunn père et fils has long been established—each willing to say nasty things to the other when necessary, but all in an atmosphere of irreverent affection—an odd couple that is still willingly together after 20 or so years.

“I was just telling Roger here about the letter you wrote to the trade that pissed everybody off,” Mike ventures, setting up the older man. Randy glances down, then quickly up again, still the grinning schoolboy caught setting off firecrackers in the churchyard during services. “Which one?” he softly asks.

A changing of the guard

While Randy Dunn’s wines still have a large and reverential following of wine lovers, whose devotion reminds one of an aging gang of Deadheads drinking wine in a fern bar, they are no longer the primary focal point of Napa Valley’s Howell Mountain wine production. Other wineries get higher ratings, sell for more money, have equally talented winemakers, and have built more impressive caves and palatial wineries set among the hillside forests. At the same time, Dunn remains Howell Mountain’s touchstone, his name coming up at least for a few moments in all conversations—often simply “Randy,” no elaboration needed—even with more recently arrived Howell Mountain producers.

According to the Howell Mountain Vintners & Growers Association, there are 16 wineries there, most founded since the 1990s—a collection of well-knowns and should-be-well-knowns, including Cade, Outpost, Adamvs (sic), Arkenstone, Robert Craig, O’Shaughnessy, Almacerro, Neal, and a reinvented La Jota. Other producers, such as Beringer, the Peter Mondavi family, Ink Grade, Cakebread, Clif Family, and Pine Ridge, own vineyards here but make the wine elsewhere. And there is always a high demand for pricey Howell Mountain fruit from producers right across northern California.

It is interesting to note that all but two of these 16 winery owners came here from somewhere else, now a mostly older first generation to both Napa Valley and the mountain. The exceptions are Mark Neal, who grew up in Rutherford, on the valley floor, before discovering hill country, and the Black Sears family, who had not previously produced wine.

“Howell Mountain is as good as there is out there for Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignons,” says wine critic Jeb Dunnuck. “It has a lot of great producers, and there’ve been a lot of new vines planted. The place has loads of energy.” And while the region was once valued primarily as a haven of old-vine Zinfandel, some planted as early as the 1800s, the continued demand for Cabernet Sauvignon, which sells for $15,000 a ton or more, has dramatically shifted that balance. Among the few whites produced on the mountain, Sauvignons are highly regarded. Howell Mountain 40 years later is much the same book, but the pages have turned.

Anatomy of a mountain

It is a mountain, yes, and a huge one, yet it’s not a completely vertical ascent, its shape that of a reclining giant. At first, it’s a bit of a hike up from the Napa Valley floor, but then there are long stretches of undulating hills and rolling uplands with almost flat benches before the terrain again climbs more sharply to a fairly level ridge line at around 2,500ft (760m). The Howell Mountain sub-appellation of Napa Valley covers 14,000 acres (5,666ha) of partially cleared forests in the eastern Vaca Mountain range between St Helena and Calistoga. Yet only about one acre in ten is planted to vines. It is still very much on the wild side in spirit and in fact, roamed by mountain lions, black bear, deer, and wild turkeys.

Though most of Howell Mountain rests within the Napa River watershed that flows into San Pablo Bay, a portion of it drapes over the ridge into Pope Valley and thus a part of the Sacramento River watershed. That difference is huge, as Howell Mountain is the rare appellation that defines its borders solely by its altitude—everything above an imaginary line that begins at 1,400ft (427m) and wraps around the mountain falls within the AVA. On the Pope Valley side, this altitude has less meaning, but on the Napa River side, it is the defining characteristic, as 1,400ft was chosen as an average level above the top layers of nightly fog.

For such a huge growing area, the basics of Howell Mountain’s terroir are relatively simple: Most soils are either volcanic tufa or Aiken loam (red clay), or a combination. Most vineyards reside above the valley’s fog layer, though the mountain still gets chilling breezes off San Pablo Bay, and its soils are well drained. The differences between individual vineyards generally stem from their varied aspects—where they lie within the folds of the mountainsides—and where they are located between the 1,400ft base of the AVA and its 2,500ft summit.

“The fog and colder wind come up the valley from the bay and are deflected by Mount St Helena [north of Calistoga] over to our neck of the woods,” says Chris Carpenter, who makes the wine at La Jota. “As much as soil type, grape growing on Howell Mountain depends on the path this cold, wet air takes. These fog pockets define a vineyard… on the Pope Valley side of the mountain, there is no fog and more sun.”

Laura Barrett is winemaker for Clif Family Winery, which owns one vineyard—Cold Springs—just above the Napa Valley fog line and another—Croquet—on the Pope Valley side. “They are just 4 miles [6.5km] apart, but drastically different,” Barrett says. “Cold Springs is cooler, with morning fog, breezy in the evening, with a long growing season, while Croquet is ten degrees [(5.6°C)] warmer and has a much shorter growing season.”

While tufa is officially listed as a major component of most vineyards, Mark Neal, who owns an eponymous winery on the mountain and also operates a vineyard service, says, “If you look it up, it’s not really tufa but more like volcanic dust.” Matilda Scott, winemaker at Almacerro, agrees. “Our soil is mainly mountain ash, a very white soil that we have nicknamed ‘moon dust.’ You can see wild animal tracks in it, as in the snow.” Whatever the soil type, the grapes on Howell Mountain tend to be rich in iron and acidity.

Although there are a few thousand residents of Howell Mountain, they are mostly scattered along a half-dozen meandering two-lane roads, mainly modest bungalows tucked into the edges of the woodlands. Most of the wineries and a few tasting rooms are located along White Cottage Road or its tributary, Summit Lake Drive.

The mountain has only one small, unincorporated village, Angwin, an anomaly among Napa Valley wine towns. Angwin has a hardware store, a supermarket, and a small college, but there are no college or townie bars there (or even a serious restaurant), since the college—Pacific Union—is owned by the Seventh-day Adventist Church, which forbids drinking any alcohol. As many of the town’s residents are also Seventh-day Adventists, Angwin remains an island of sobriety in a sea of wine producers.

There appears, however, to be little, if any, animosity between winegrowers and abstentionists. “We enjoy each other socially and as individuals,” says Kelly Morris of the Evangelism Network in Angwin, “but we don’t collaborate on community projects.”

A name on the label

America’s modern wine industry is still less than 100 years old and seems younger. Prohibition was enacted in 1920, and when it officially ended 13 years later in December 1933, almost all continuity of production with the past, even at the family-farm level, had been severed. As a result, every California wine region, and almost every California winery, seems to have intriguing origin stories of modern-day settlers coming from elsewhere, beginning in the 1960s, to stake out their vinous claims with little or no prior experience, yet achieving success against all the odds.

So it was with Howell Mountain. The region has a rich winemaking history dating back to the Gold Rush days of the 1840s and ’50s, a time when fortune-hunters and opportunists from Europe and America’s East Coast flooded northern California, still a part of Mexico until 1848. After Prohibition, the mountain remained dotted with these abandoned vineyards and ghost wineries. By 1970, there were no commercial wineries there.

Then, in early 1983, four newcomers who had begun growing grapes on the mountain over the previous dozen years—Dunn, Mike Beatty, Robert Brakesman, and William Smith—gathered around Beatty’s kitchen table, trying to figure out whether Howell Mountain could become an official American Viticultural Area, or AVA. AVAs were a new invention, established only in 1978, when the federal government decided officially to follow the European model of recognizing approved wine-growing regions listed on wine labels.

“I had been selling grapes to Ridge [in the Santa Clara Mountains], as well as Cakebread and other wineries,” Beatty says. “Ridge liked to identify the source of their grapes and had been putting ‘Howell Mountain’ and sometimes ‘Beatty Ranch’ on the labels. Then we learned we would have to become an AVA for that practice to continue. So, we spread a topographical map on the table, anchored by our wine bottles, to draw boundaries that would include all of us.”

The men were all college graduates or professionals. Beatty was a Stanford alumnus who had sold pH meters to winemakers. Dunn graduated from the University of California at Davis and was also making wine for Caymus on the valley floor. Brakesman, who owns Summit Lake Winery, had a degree in chemical engineering, and Smith, now deceased, was a land investor for an oil company, having just purchased a 4,500-acre [1,820ha] ranch in Pope Valley for his firm. For himself, Smith acquired the old La Jota winery property, purportedly as a tax shelter.

The fifth member of the group, Robert Lamborn, who wasn’t at the map-drawing, was a private investigator whose most notorious case involved being hired by the family of Patty Hearst, the newspaper heiress who was kidnapped in 1973 by a gang of political dissidents.

Once Howell Mountain’s proposed AVA boundaries were made public and received no objections, they were swiftly approved on December 30, 1983, and the AVA became official in early 1984. The approval notification attested to the AVA’s modest beginnings, noting it had “198 acres [80ha] of grapes and two bonded wineries”—Dunn and La Jota. Howell Mountain thus joined Los Carneros, approved the same year, as the first sub-AVAs in Napa Valley, though Los Carneros also spreads into neighboring Sonoma County.

Perhaps as important as the establishing of the AVA was the sudden emergence shortly thereafter of Dunn’s high-scoring, high-priced Cabernet Sauvignons, with their distinctive diagonal labels and red-wax seals, not only putting his winery on the map but also announcing to the world the coming importance of Howell Mountain red wines.

In some ways, these early creators of the Howell Mountain AVA saw themselves the same way as the state of Texas famously sees itself within the US—a part of the whole but still retaining a certain independence. In the AVA’s case, the governing body is the Napa Valley Vintners (NVV), without a doubt the most powerful AVA administrator in the US, and one that isn’t hesitant about exercising its authority over its 16—and counting—“nested AVAs,” as it likes to refer to them. Membership in the NVV is optional, and, not surprisingly, Dunn, along with Black Sears and Spence, are not part of the organization.

Not wanting to be eclipsed in popularity by Howell Mountain or any other offspring, the NVV convinced the California state legislature to enact a law in 1990 forbidding any Napa Valley winery from displaying its sub-AVA larger or more prominently on a bottle label than Napa Valley. According to Rex Stults, who heads the NVV name protection committee, the rule is vigorously enforced. Sean Capiaux, president and winemaker at the O’Shaughnessy Winery on Howell Mountain, can attest to this. “We wanted to emphasize Howell Mountain on our label, because we figured everyone knew that Howell Mountain was in Napa Valley,” he says, “but the Vintners forced us to put Napa Valley the same size on the label. There is still a strong following in the marketplace for Howell Mountain wines.”

The coming of the new guard

Although the new group of winery owners didn’t begin arriving until the 1990s, a few got running starts by taking over existing properties, some with significant histories. For example, when Jackson Family Wines purchased La Jota in 2005, they bought a winery with a century-old backstory. Founded in 1898 by Swiss immigrant Frederick Hess, it lay dormant until 1982, when Bill Smith took over the “ghost winery,” Howell Mountain’s oldest bonded winery. In 2001, an aging Smith sold the property to Markham, which renovated the winery before selling it on to the Jacksons.

By heritage and market reputation, La Jota stands as perhaps the most prominent of Howell Mountain’s new guard, with three vineyards totaling 28 acres (11ha), mainly planted to Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, and Chardonnay.

“I started with Jackson Family in 1998,” says winemaker Chris Carpenter, who also oversees production of the Jacksons’ other Napa Valley brands, including Cardinale, Lokoya, and Mt Brave. “In 1995, Jess and Barbara had purchased the old WS Keyes property on Howell Mountain from Liparita to supply Cardinale with fruit. When La Jota became available in 2005, we jumped on it because of our experience at Keyes.” The Keyes vineyard, which came with Merlot plantings, is now part of La Jota. “I had a long-standing love for mountainside Merlots,” Carpenter says, “but this was about the same time the film Sideways [which trashed Merlots] came out, so Jess had some reservations about having a Merlot. We started with 200 cases. Now it’s almost 4,000, and in some years it’s more highly rated than the Cabernet.”

Following his sale of La Jota in 2001, Smith and his wife, Joan, retired to a nearby property, built a rudimentary winery, and started producing an eponymous wine. Fifteen years later, they sold it to a Boston patent attorney, Frank Scherkenbach, who renamed it Almacerro. “When I first came, the place was a bit primitive,” says winemaker Matilda Scott. “There were no doors on the winery, and there were open-top tanks everywhere because Bill liked to make Pinot Noir. Today, we’ve modernized the winery and humidified the cave.”

Still, Almacerro, located along a promontory about a mile past La Jota, has one of the most primitive settings on the mountain. “We’re one of the last frontiers of the AVA,” Scott says. “We’re at the tip of Howell Mountain—no other vineyards or wineries around, just forest and fresh air from San Pablo Bay.”

Cade, owned by the PlumpJack group of wineries and restaurants, is part of a third historic Howell Mountain property. Cade bought its first vineyards there in 2005 and made its first vintages at the PlumpJack facility in Oakville while building a winery at the vineyards.

“We bought a second property, now called 13th Vineyard, which had been owned by Ladera, in 2016, and it came with its own old stone winery,” says John Conover, general manager of PlumpJack’s Napa Valley estates. “The floor of Napa Valley is like a quilt of vineyards, while Howell Mountain is a patchwork of properties.” PlumpJack’s part of that patchwork covers 82 acres [33ha], which Conover believes to be the biggest holding on the mountain.

“The 13th is where two French partners, Jean Brun and Jean Chaix, planted Bordeaux grapes and built the winery in 1886,” Conover continues. “I imagine the old stone building has survived a lot of wildfires.” It is still in production, making Cade wines.

No one would mistake Arkenstone’s winery as a relic of the 19th century. The property was purchased by Ron and Susan Krausz in 1988, but planting didn’t begin on the current 13-acre [5ha] vineyard until the 1990s, and the first vintage was not produced until 2006. The winery—an opulent, multilevel, gravity-flow facility—is outfitted with elevators, open galleries, and extensive caves.

“Howell Mountain is a winemaker’s playground,” says Sam Kaplan, Arkenstone’s winemaker. “The volcanic soil is well drained, so the vines are stressed and have smaller berries. With all the different aspects and exposures, our vineyards dictate we make a lot of small lots.”

Somewhat surprisingly, most post-Prohibition winemaking families on the valley floor either didn’t have a high regard for Howell Mountain fruit or were somewhat intimidated by it. Alycia Mondavi relates how her grandfather, Peter Mondavi, was mistrustful of mountain wines (as, apparently, was his brother, Robert Mondavi); it wasn’t until he was nearly 100 that Peter became a fan—and, even then, only after tasting those made by Alycia’s sister, Angelina, under the Dark Matter and Aloft labels. “Howell Mountain was a big learning curve for us,” Mondavi says. “We weren’t used to working with these big tannins.”

Mark Neal faced a similar, yet different, hurdle. At Rutherford, on the valley floor, he and his father, Jack, had been pioneers in organic farming in California. “With our vineyard services, my dad and I asked, ‘Can we do this type of farming in the Carneros or American Canyon or Howell Mountain?’ We had only two organic products to work with when I was a kid. Today, we can farm organically anywhere without a problem.” That includes the 12.5 acres (5ha) of vines he now owns and where he makes Neal Family wines from land purchased in 1990.

The wineries farther up the mountain past Angwin are less affected by the daily morning fog line. One of them, O’Shaughnessy, owned by Midwesterners Betty O’Shaughnessy Woolls and Paul Woolls, takes its playbook from Bordeaux. “We are the only Napa Valley property that has planted all eight of the original Bordeaux varieties,” says winemaker Sean Capiaux, “including Carmenère, St Macaire, and Gros Verdot. We wanted to produce a more contemporary wine than the [very tannic type that is the] image of Howell Mountain,” he continues, “so we use these lesser grapes to complement the Cabernet Sauvignon and to soften its tannins.”

As with other properties within the AVA, O’Shaughnessy’s 37 acres (15ha) of producing vines are only a small part of its total estate. “Because of habitat rules, we can only use 40% of the property for vineyards,” Capiaux explains.” The rest is forest and open land.

Near the top of the mountain, along Summit Lake Road and not far from Randy Dunn’s pioneer estate, are two wineries originally founded as family businesses, but that have seamlessly transformed to corporate management: Robert Craig and Outpost.

In the early 1990s, Robert Craig left his job at the Hess Collection to start his own winery with three business school friends as partners. At first, Craig produced wines from other Napa Valley vineyards, but in 1995 he purchased 22 acres (9ha) on Howell Mountain and later built his eponymous winery there. In 2004, he hired Elton Slone to run the winery.

“When I interviewed, it was with the understanding that I eventually would have equity,” says Slone, who became interested in wine while a college student in Indiana and who is now the managing partner of the group. “When Bob retired in 2012, he had only 20% of the business.” Over the years, Robert Craig Winery has trod the same path as a few other Napa Valley producers, making estate wines and buying fruit from multiple Napa Valley mountain vineyards in the eastern Vaca Range and the western Mayacamas Mountains.

“About 90% of our wine is estate fruit,” Slone says, “and about 60% of that is from our Howell Mountain vineyards.” With his broader perspective, Slone isn’t hesitant to consider a quality ranking of Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignons by growing area. “Oakville is first, I think, and Pritchard Hill and Howell Mountain come next. Then, Mount Veeder and Spring Mountain.”

Perhaps the most fascinating, as well as one of the two or three best wineries on Howell Mountain, is Outpost, a wine producer that few in the wine trade, except serious collectors, know much about. Frank Dotzler and his former wife came to the mountain in 1997 and purchased True Vineyard. In 2003, they bought what is today the primary Outpost vineyard from a family who had in turn purchased it from Bob Lamborn, one of the five modern pioneers of Howell Mountain. “When I got here [to Outpost], everything was about two thirds Zinfandel, while my True Vineyard was Cabernet, Cabernet Franc, and Merlot,” says Dotzler, who came to Napa Valley from the computer industry.

With Napa Valley consultant Thomas Rivers Brown making the wine, success came to Outpost almost overnight. “I showed it to [Robert] Parker for the first time with the 2006 vintage,” Dotzler says. “He jumped on the Outpost 2007 with a 98-point rating. In 2014, he gave us 100 points.” Counter to Howell Mountain’s reputation, Outpost’s Cabernet Sauvignons, Zinfandels, and red blends are silky and supple, somewhat similar to the top crus of Pomerol.

Unfortunately, personal circumstances led Dotzler to sell the winery, and Outpost’s high ratings attracted many would-be takers despite the recession. “None was interesting to me until Christian Seely came along,” Dotzler says, referring to the well-known head of the worldwide chain of premium properties owned by AXA, the French insurance giant, which purchased the winery in 2018. “Christian told me he wanted to leave Outpost the way it was, that it was not just an investment but something AXA intended to keep. And he asked me to stay on. Christian has come through on everything he said.”

Brown also continued as winemaker, but Seely did want to make a few changes. A nearby 16-acre (6.5ha) property was evaluated and purchased, raising vineyard acreage to 45 (18ha) to meet AXA’s goal of having at least modest international distribution for its portfolio wineries; a second label was also added to the brand. When Seely expressed a desire for a Pinot Noir property, “I was asked to find it for them,” Dotzler says. He recommended the well-regarded Platt Vineyard on the Sonoma Coast, which became part of the AXA portfolio in 2022.

A final high-profile property that should be mentioned among the new guard is Adamvs, purchased in 2008 by entrepreneur Stephen Adams, who died in March 2024, and his wife Denise. Another well-known Napa Valley consultant, Philippe Melka, makes the Adamvs wines.

Odd man out

There is another Howell Mountain winery story that needs to be told—the one about the winery that was left behind.

Of the five original founders of the AVA, Randy Dunn still makes wine; Mike Beatty sells grapes and makes wine at his Howell Mountain Vineyards, as does Bob Brakesman at Summit Lake. Bill Smith sold both La Jota and his eponymous winery before he died, as did Bob Lamborn with his vineyard. Lamborn’s son, Mike, retained the family wine brand but sold his vineyard in 2023.

Then there was Burgess Cellars. Tom Burgess founded his well-regarded winery on Howell Mountain as part of the Class of 1972, the same year Diamond Creek, Silver Oak, Franciscan, Clos du Val, Sullivan, Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, Stags’ Leap Winery, and Mount Veeder all put down roots. Yet for some reason, Tom Burgess was not included in the five-man group that decided the boundaries of the Howell Mountain AVA. So, when the AVA limited its wineries to those above the 1,400ft level, Burgess Cellars, at around 900ft, was left out.

Like many stories, the reason behind the Burgess omission is remembered differently by those who witnessed it. Dunn says, “We asked Tom Burgess if he wanted to join, but he said, ‘You guys go do your own thing,’” adding there was a small ante everyone was asked to contribute to the cause. Mark Neal says he heard it was a more significant sum for the times. “They wanted $500 to help pay for forming the AVA, and Tom didn’t want to pay it,” Neal says.

Burgess’s son Steve, who owned the family winery before selling it to Lawrence Wine Estates in September 2020, says his father, a former pilot, was simply a stickler for following regulations and details. “He told me he told them, ‘What you’re describing is not what I have. I’m below the 1,400ft fog line.’ One of them—I’m not sure who—told him they were glad that he declined, that they just wanted to give him the opportunity.”

Recently, I related these differing versions to Mike Beatty. Beatty paused briefly, then said, “I’m not going to argue with them. But I was the one who was tasked to drive down the mountain and break the news to Tom that he wasn’t part of the new Howell Mountain AVA.” Then he added, “But people will believe what they want to believe.”

As fate would have it, whether or not Burgess should have been included in the Howell Mountain AVA became moot in late September 2020, when, a couple of weeks after the winery sale was made final, the Glass Fire swept down Howell Mountain and destroyed Burgess Cellars. The new owners quickly relocated the Burgess brand to the former Luna winery in Napa city.

Having missed out on the birth of one AVA, Steve Burgess, who no longer owns a winery, is now the anxious birth parent to another nested AVA, the newly formed Crystal Springs of Napa Valley AVA, which blankets the Howell Mountain foothills that fall below 1,400ft. “I started the process when I still owned the winery, but it was 12 years in the making,” he says. “I decided to finish the process.”

One additional irony to the story: The company that bought Burgess, Lawrence Wine Estates, also bought Heitz Cellar about five years ago. And Heitz owned Ink Grade vineyard atop Howell Mountain overlooking Pope Valley, using its Cabernet Sauvignon as blending grapes. “We tasted a couple of the early ferments and decided to keep them separate,” says Lawrence managing partner Carlton McCoy Jr, and the group has now launched Ink Grade as a separate brand. “Ink Grade is an east-facing vineyard, so it can produce a more elegant wine, unlike the image of Howell Mountain as big, tannic wines. It gives us a real Howell Mountain niche opportunity.”

Rather than going through the rigors of trying to get a winery approved for the top of Howell Mountain, McCoy says, “We already have a winery permit where the one burned on the Burgess property, so we will build the Ink Grade winery there.” At long last, the old Burgess estate will finally officially produce a wine from Howell Mountain.

A future without gentrification?

Look at a wine map of Howell Mountain or a close-up from Google Earth, and you will notice a lot of open, unoccupied space, much of it still forested—plenty of room to locate new vineyards and new wineries. Yet it is unlikely there will be any rush to add to the mountain’s capacity and gentrify the neighborhood anytime soon. Napa County has over the years developed strict zoning laws to protect the environment, especially from erosion, as well as to encourage biodiversity in plants and animals. Not surprisingly, it has been 22 years since a new winery has been constructed on Howell Mountain—Spence, in 2012.

In November 2023, the Napa County Board of Supervisors voted to reject a high-profile project near Angwin known as La Colline, which proposed clearing 30 acres (12ha) of land, part of an 88-acre (35.5ha) tract, to plant a 20-acre (8ha) vineyard. And Alycia Mondavi says, “We’ve spent more than a million dollars and are now 14 years into trying to get a winery on Howell Mountain for our wines.”

Whenever this subject of expansion comes up with winemakers and winery owners on the mountain, there is a pause and then their words are—mostly—chosen carefully. Mark Neal’s reaction is typical. While saying he’s not opposed to more vineyards in theory, “If the project gets into a lot of work moving dirt and removing trees, that’s another matter. We need a biodiversity of plants. Right now, on the valley floor, it’s vine row to vine row from Calistoga to Carneros.”

“It’s tricky,” Cade’s Conover agrees. “I understand both sides. People say, ‘You’re just another NIMBY [not in my backyard].’ While there are still areas on Howell Mountain that could be planted, we need to manage and control growth.”

As a result, the continued revitalization of Howell Mountain will likely come via another very familiar path—simply buy an existing vineyard or winery, however high the price. Today’s collective of winery owners are well into middle age and subject to the three terrible Ds of the financial apocalypse: Debt, Divorce, and Death. Most likely, any immediate changes on the mountain will come from a third wave of investors, like AXA at Outpost, and dreamers who made fortunes elsewhere and now want to make wine in Napa Valley.

When Mike Lamborn sold his vineyard, one with no winery, atop Howell Mountain in 2023, the buyer was a family from Singapore who moved to the US about ten years ago. “Dad always liked French wines, but when we came to the US, he fell in love with Napa Valley wines and the history of the area,” says Colin Yuan, a professional photographer and a student at the University of Chicago. “So, when the Lamborn property was for sale, we purchased it. It’s a lovely vineyard, about 7 acres [2.8ha], with a view of Pope Valley. Everything there is so new to us.”

It will be named Mars Estate for Colin’s father, Mars Yuan, CEO of the US unit of HaiDiLao Hotpot, and the first vintage, a 2022 Cabernet Sauvignon, is now being made at a Calistoga contract facility. “Heidi Barrett is making the wines, as she did for Lamborn,” Yuan says, “and we were lucky to get Steve Matthiasson to take care of the vineyard.”

Incidentally, Mars Estate is pulling out the last two acres (0.8ha) of Lamborn’s legacy Zinfandel vines and replacing them with Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Petit Verdot. “We would like to build a winery on Howell Mountain,” Colin Yuan adds, “but that may take some time.”

Does having the wineries and vineyards spread out across the vastness of Howell Mountain make for better neighbors? Because no matter how much winemaking on Howell Mountain has matured and modernized, whether you talk with old-timers like Beatty or Dunn, or relative newcomers like Dotzler and Conover, you will hear the same story: There exists a special bond among Howell Mountain producers, regardless of where they are located or how long they’ve been there.

“This community is strong,” says Arkenstone’s Kaplan. “Whether it’s responding to the fires or when we hold group events or do a Howell Mountain wines road trip, it’s a tightly knit group. The other regions envy the organization that we have on Howell Mountain.”

It remains the same book, but the pages have now turned to a new chapter.