The honey of the bee, as well as the juice extracted from grapes, are called madhu,” states the Arthaśāstra, a 2,000-year-old compendium of statecraft and domestic economy written at the Mauryan court of India. This first piece of intelligence comes in a section offering advice to the superintendent of a royal storehouse (II: XV).

Further on in the text, in a recitation of the duties of a superintendent of liquor, whose job involved overseeing the disporting of merchants with their mistresses in “half-closed rooms,” the most prized intoxicating drinks are listed. They include various honeyed and spiced fermented potions made with jaggery (unrefined palm sugar), tree bark, or rice, long pepper and black pepper, cinnamon, turmeric, and the psychoactive betel nut, but the confusion for the wine historian sets in with reference to madhu.

Whereas rudimentary recipes are given for the drinks mentioned beforehand, their proportions stated relative to each other, madhu is identified by what appear to be its notable appellations. “Madhu is grape juice,” states the text. “Its name, according to its place of origin, is Kāpiśāyana and Hārahūraka” (II: XXV).1 In a recent authoritative scholarly work, An Unholy Brew: Alcohol in Indian History and Religions (2021), James McHugh identifies the first of these locations as Kapiśa, near Begram in present-day Afghanistan, while the second remains uncertain. The point is that madhu is not a drink to be blended by the quartermaster, but is imported ready-made from further west, from lands where it arose from a native tradition—Persia, ultimately.

Can we be sure, though, that every drink designated as madhu in the ancient texts was grape wine? The answer is no. McHugh, associate professor of South Asian religions at the University of Southern California, emphasises at various points in his study that the term is marked by elusive ambiguity. If madhu is at once honey and the juice of grapes, it might sometimes designate imported grape wine, and at others refer to a fermented honey drink. It is, by distant etymology, the Proto-Indo-European root of the word “mead” and its various cognates.

Madhu, mead, and intoxication

The tantalizing aspect of this semantic slippage is that, as far as we are currently aware, the usage in the Arthaśāstra of madhu to mean grape wine is its earliest recorded example in India, which perhaps suggests that it was mead before it was wine. McHugh offers an estimate for the composition of the text as around the turn of the Common Era, but parts of it may conceivably be as old as the third century BCE. Whatever its precise identity in varying contexts, it derived originally from the Sanskrit term mada, meaning intoxication of all sorts—a state of consciousness that could be induced by gambling or by power, as much as it was the direct result of consuming intoxicants such as betel, cannabis, the intensely toxic datura (thorn-apple), or wine.

What the common term for mead and wine indicates is that, in its earliest manifestations as a cultivated product, it was the duty of wine to be sweet. Many methods evolved in Europe and the Near East to ensure such a quality, from harvesting the grapes as late as possible to concentrate their natural sugars, to drying them either on the vine or after picking, or by the ancient ingenuity of halting the fermentation of the sweet juice by immersing the amphorae in cold water until the arrival of winter. Wines that fermented until they were drier, or what ancient taste would have considered sour, had to be sweetened back with the addition of honey, unfermented grape juice, or—as in ancient Rome—defrutum or sapa, glutinous syrups made by boiling down grape must.

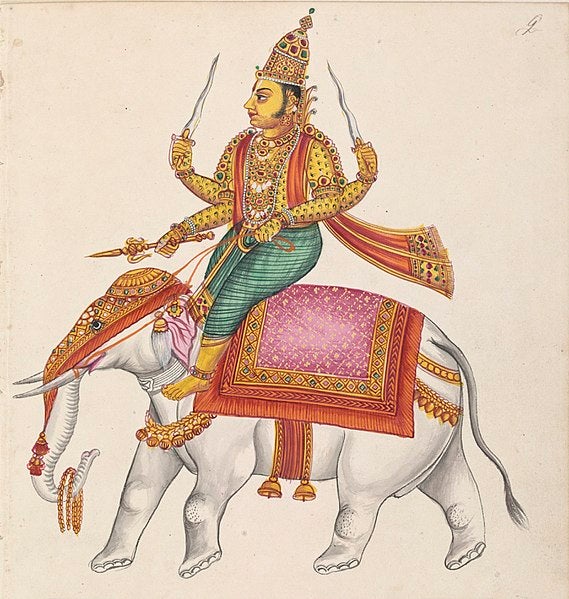

Suggestively, the state of mada is also associated in the Vedic texts with consumption of the sacramental drink, soma, produced from the pressed, but unfermented, milky sap of a plant whose identity has been an ethnobotanical enigma for centuries. It seems likely that this was a potently psychoactive brew similar to the elixir consumed at the Eleusinian Mysteries of Classical Athens. It may have been Indian rue, ephedra, even one of the species of hallucinogenic mushroom. It may have been barely more psychoactive than tea, except that accounts of the effect of it suggest something fairly dramatic, as would befit a ritual drink.

The soma sap was generally described as acidulous, and was mixed with milk and water, less often honey, so that it was not typically sweet. In the accounts of the god Indra drinking soma to fortify himself in his battle with the serpent Vritra in the Rigveda, the balance of its properties is clear: “Sweet to thy body let it be, delicious be the savoury juice: / Sweet be the Soma to thine heart” (trans. Ralph T. H. Griffith, 1896, XVII: 6)2. To discover the sweetness of intoxicants, be they mead, wine, or psychotropic sacrament, we should attend not to their actual sugar content, but to the intoxication principle itself, a luxurious salve to the body and the heart of humankind as well as of gods.

1 Quoted (and translated) in James McHugh, An Unholy Brew: Alcohol in Indian History and Religions (2021), New York: Oxford University Press, 53.

2 https://archive.sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/rv08017.htm