“The back taste is very special—there is the taste of hope,” quips Lamberto Frescobaldi to sum up the special identity of the wine produced on the penitentiary island of Gorgona.

But there is genuine sentiment behind the witticism. Since 2012 Frescobaldi has invested both emotionally and financially in this project to rehabilitate prisoners through in-depth training in viticulture, not only to benefit the individuals but as part of a wider sense of social responsibility. “It has been a way to be a bit more humble about myself, life and success,” Frescobaldi adds. “We think we are drivers of ourselves, but we are so damn lucky.”

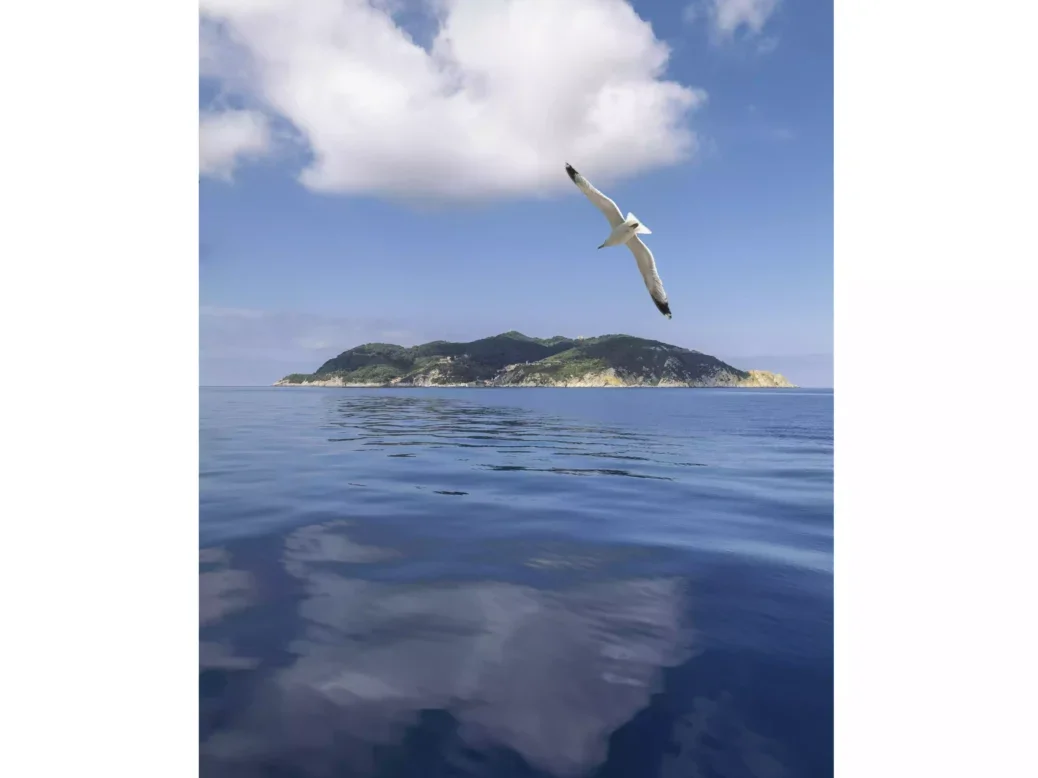

It was my curiosity about this social project, rather than any expectation of the wine, which prompted me to accept an invitation to Gorgona, the last remaining penitentiary island in Europe, for the launch of the 12th vintage of Gorgona Bianco. But as we climbed the hill through the prison into the vineyard things looked much more promising than I had envisaged.

The small 2.3ha (5.7 acres) vineyard cloaks a natural amphitheater and the southeast facing slope is sufficiently steep to warrant terracing with dry stone walls. In the lower section the terraces were constructed by five Albanian prisoners in 2015 and planted with gobelet (bush vines) of Vermentino and Ansonica. It’s too windy here for trellising. Towards the top of the hill at 150m (490ft) the original 1ha (2.4 acres) parcel was planted in 1999 from which the inmates made a rough wine sold to the prison guards.

But the vines were abandoned and overgrown by 2012 when Mrs Giampiccolo, the prison director at the time, contacted two hundred wine producers to gauge their interest in a collaborative winemaking project with the penal colony. To his credit Frescobaldi was the only person to respond and despite the grave misgivings of his wife, visited the island. “I saw the vineyard and it was breathtaking and the people were breathtaking,” he recalls. “When I returned my wife said ‘I can see it in your eyes. You have said yes.’”

It was serendipity. Two things came together—the merit of the project and the potential of the site. It was encouraging to find remains of vineyard terraces close by the ruins of a Benedictine monastery. The project was swiftly underway. An inmate from a winegrowing family in Sicily set to clearing the vineyard and Frescobaldi’s head winemaker Nicolò D’Afflitto was shipped in to make the first vintage in 2012. “I understood quickly it was a unique place: The combination of the blue sky, the light, the sun, and the magmatic soil,” he said. Glancing at the earth, the top soil was sandy and red with iron, but beneath and protruding was stratified rock. The sea surrounding this small island modifies the temperature, so it escapes the extreme summer highs experienced in Tuscany. Francesco Duranti, who has made the past eight vintages on Gorgona, says the “vines don’t stress, despite the lack of rain, because of the high humidity and so the vintages are relatively consistent in comparison to the mainland.”

Gorgona, training, and rehabilitation

Over the past 12 years Frescobaldi agronomists and winemakers have trained the inmates to work in the vineyard and winery. Only five prisoners are taken on at a time, and there is constant rotation so the opportunity of this apprenticeship is available to everyone interested. The two or three years of rehabilitation on Gorgona represent the tail end of 25–30 year sentences for serious crimes, but no mafia or sex offenders are allowed on the island. Frescobaldi pays them €12.50 an hour—the prison services pay just €3—which enables inmates to save a surprising sum to get them started in civilian life, helping to take away some of the financial pressure that might lead them to fall back into crime. In 2014 Frescobaldi signed a 15-year contract with the penal colony to offer the trained prisoners a year of work with the Marchesi Frescobaldi Wine Estates after their release, although not everyone takes this up. The infamous inmate who shot Maurizio Gucci, the head of the eponymous family fashion house, in 1995, “felt it was sufficient to leave with €40,000 in his bank account,” recalls Frescobaldi. Little wonder that Gorgona Penitentiary receives applications from 30 prisoners a month to be transferred to the island.

The inmates are locked in their cells at night, which presented an issue in the early days when it came to the timing of treatments, so certain rules were flexed to accommodate the proper running of the vineyard. Frescobaldi explains that he wanted the vineyard sprayed with sulfur at 6am, (the vineyards are managed organically) so the doors of the prisoners were opened and the prisoners were trusted to return after their work was completed.

The winery is a simple set up in an outbuilding equipped with a little pneumatic press and stainless steel tanks tailored to small batch fermentation, as just 700–800kg (0.8–0.9tons) of grapes are picked a day during harvest. The following February the barrels are taken by boat the 38km (24 miles) to Livorno on the mainland and thence to Frescobaldi’s wine facility outside Florence. The red continues maturation in amphora for 18months while the white is bottled. At dinner Ristorante Frescobaldi in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria, the evening before the Gorgona visit, we tasted the 2021 Gorgona Rosso, Costa Toscana IGT Rosso which has just been released. A light and crisp wine with a gentle herbal aroma and finely grained texture. Well made and well balanced and while not especially long or intense, it is perfectly pleasant. (The 2019 is €255 on the wine list.)

You will be lucky to buy any 2023 at a retail price as just 800 bottles were made. It is largely Sangiovese with a little Vermentino Nero for colour. Frescobaldi’s thoughts on the Rosso? “There are shades and lights in every wine. I don’t want to offend Aubert de Villaine, but if every wine were perfect it would be boring. You must always be unhappy with what you are doing.” The first vintage was 2015. Maybe he means the red is a project in progress.

A social project and a human-interest story

The Gorgona Bianco, of which there are 30 barrels (9,000 bottles), was served at an alfresco lunch for 250 guests on a terrace outside the prison. The meal was prepared by a small team of inmate chefs from Bollate Prison near Milan which has a restaurant open to the public. There were at least 100 international media across all platforms and fields, for this social project is pitched by Frescobaldi’s marketing team as a human interest story. There is no denying the public relations value of this once-a-year bonanza to show the new vintage.

The 2023 Gorgona Bianco Costa Toscana IGT Bianco 2023 is a light and breezy wine. It has delicate notes of almond with a hint of mint and lemon peel. It opens up to reveal white peach and a touch of apricot skin, but the shape remains linear and the streamlined palate carries to a delicate saline finish. It carries in its wake a waft of ozone. There is no malolactic which no doubt helps with the delicate freshness of this vintage, but August in 2023 was cooler than average. The temperature warmed up in the last week and a warm September followed.

“I am always sceptical when sommeliers describe the wine as salty—I did not understand it,” D’Afflitto says. “But I analyzed the salt content for the first time and found it was double that of Vermentino in other parts of Tuscany. [0.5 g/l expressed as sodium chloride versus 0.05-0.2 g/l]. This salt comes from the soil and is carried on the wind.”

The current blend for Gorgona Bianco is 80% Vermentino with Ansonica making up the balance. “Ansonica can cover the terroir,” says Duranti to explain the emphasis on Vermentino made possible with the 2015 planting.

Despite the punchy prices asked for Gorgona wine, “it’s not economically sustainable,” Frescobaldi says. “I am doing it because of my curiosity about wine. I used to go every month and every time I left I was emotional. You don’t appreciate freedom as much as when you touch how important it is.”

But prison director Mrs Giampiccolo was more pragmatic with a clear goal in mind. “She wanted to open this house of detention to entrepreneurship. She said to me ‘Frescobaldi don’t fall in love. We want you to stay here. Life is all about numbers and we need to drop the numbers of re-offenders.’” Eighty-five percent of Italian prisoners re-offend, while the rate of reoffenders from Gorgona is close to zero I am told. Frescobaldi goes on to say “every person in prison costs €200 a day. The objective here is to give them confidence, a reason to jump out of bed in the morning to do a job, to do it well, and to become taxpayers. This project gives them the possibility to gain a new life.”