The little world of the Bordeaux wine trade, setting aside the parlous state of France’s domestic economy, has yet to grasp just how much its wines have fallen out of favor—what’s known as “Bordeaux bashing.”

The 2023 en primeur campaign has been an inglorious failure, despite some dramatic price cuts for wines that were very reasonably priced to begin with (a Burgundy or other equivalent would cost you a lot more) and, above all, of a quality to rival the best-ever released en primeur. Considering the low volumes offered for sale, one would have expected better, but then very few want Bordeaux anymore—neither here in France nor beyond home borders. Sommeliers aren’t serving it, wine merchants aren’t buying it, and wine lovers aren’t drinking it, helped by equally disenchanted wine writers.

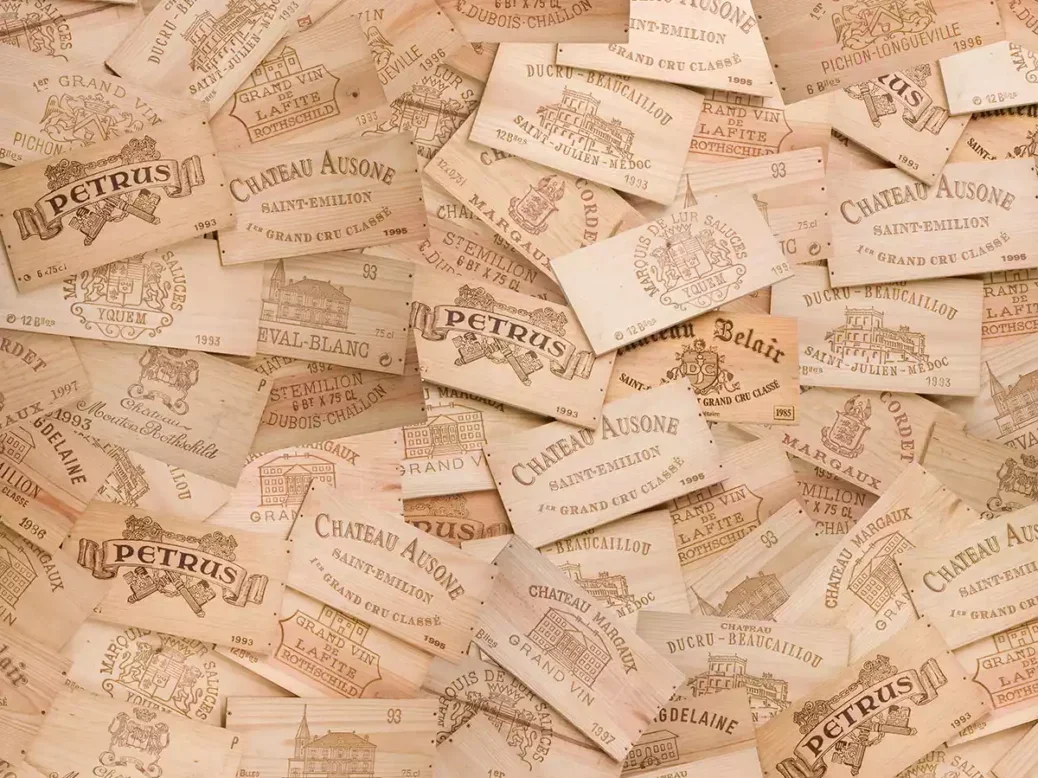

By way of example, last June, in a nice restaurant-cum-wine-bar-cum-wine cellar, I saw dozens of crates of famous Bordeaux wines used as decor. These were original crates, not just decorative panels stamped to look like wine crates. The wines they contained came from everywhere—Italy and Spain included—except from the crates themselves. The only Bordeaux for sale (this was in Burgundy, admittedly) was a very average bottling with nothing to recommend it save gluggability—that glou-glou, slips-down-a treat quality that people like these days but that is particularly ill suited to Bordeaux. The caviste smiled when I commented on his taste in decor, as if to say, “What choice did I have?” Not that he could be faulted on his wine selection, which featured a very carefully and responsibly chosen range of French wines.

Bordeaux and the folly of speculation

One glance at the menus of trendy restaurants or the wine lists of equally trendy wine merchants (competent and incompetent alike) is enough to make one realize that Bordeaux wines are conspicuous by their absence, no matter how inexpensive or environmentally friendly they may be. We French, of course, have always delighted in breaking the toys we no longer want. But for years now, the responsibility incumbent on Bordeaux producers and distributors has been quite as great as their refusal to admit it.

The period 1930 to 1985 was a difficult time for Bordeaux, but after that the industry made a lot of money by sticking to wines with high markups—the wines most in demand on the global wine market, so requiring minimum effort on the part of the seller. In doing so, the Bordeaux wine trade ignored its responsibility toward the rest of the wine world by slapping a château label on every bottle. The fact that it was all smoke and mirrors didn’t stop supermarkets from stocking hundreds and hundreds of so-called petits châteaux, all selling at much the same price and equally baffling for the customer faced with row upon row of wines they’d never heard of. Undistinguished terroirs and pleasureless palates were of little concern to the major buyers: The wines sold well, and what did consumers know anyway? By the time sales began to fall off, it was too late. The nous displayed by the Champenois in creating top-value, own-brand supermarket Champagnes was sadly lacking in their Bordeaux counterparts—this, despite the brand equity vested in the name of the world’s most famous wine region.

However, the real and most serious problem with the Bordeaux wine trade is its “buy low, sell high” business strategy: speculation, to call it by its proper name. Restaurateurs, wine merchants, distributors—people in the business of buying wine absolutely rely on speculation. But private clients? Whose crazy idea was it that buying wine futures—bought and paid-for sight unseen—made financial sense for private individuals? Even when they do get to taste the wine, it is morally indefensible to suggest that your average punter can tell what a wine will be like from the tokenistic sample drawn from the barrel after just a few weeks’ aging.

And this, of course, is where your self-proclaimed experts come in—the pundits who deal in demagoguery. No formal training, perhaps, just a powerful tendency to deliver near-perfect scores rather too often. In the end, however, people realize that there are a lot more losers than winners in this game, with wines turning up on supermarket shelves at the same price (or almost) that they were sold en primeur five years earlier. It turns out that making easy money isn’t that easy; but rather than admit to being suckered by greed, it’s far better to blame the system and the product.

Going one of two ways

This can go one of two ways. One way is to stop buying Bordeaux altogether, on the grounds that producers care more about the sale than the origin, and more about money than quality and product authenticity. The other way is to buy only the most famous brands for investment purposes—in other words, become a big speculator yourself. Invest in famous wines as you would high-performing stocks—not to drink them, not even as a consolation, but to resell them and, in the process, fuel those speculative bubbles that explain the otherwise inexplicable price disparities between what are, in the end, wines of a very similar caliber. I am appalled by the increasing availability of speculative financing loans. Speculation brings disgrace on the very flower of agriculture. It reduces wine to a status symbol for rich buyers from prosperous countries—or a crutch for insecure social climbers hoping to claw their way to the top. ▉