Chloe Ashton considers whether the Bordeaux en primeur system has fallen so far out of favor that it is perhaps not much longer for this world.

This is not another Bordeaux en primeur article. By the time of publication, the 2023 Bordeaux en primeur campaign will be coming to a close. Forgive my brutal realism, but I don’t believe it will be a successful campaign (though I’d be very pleased and relieved to be proved wrong). If my modest tenure of 11 en primeur campaigns has taught me anything, it’s that Bordeaux en primeur prices are never as low as the trade might wish them to be (with the exception of 2019) and that price is virtually all that matters in sorting wheat from chaff during a one- or two-month period when more than 300 wines are released onto market. At the time of writing, the first few major 2023s to have declared a price have met mixed reviews. Stephen Browett, chairman of Farr Vintners, tells me, “Lafite has worked because it was priced (to the consumer) lower than any physical vintage. That is the purpose of en primeur, and it was good that they came down to the right price. Léoville-Las-Cases came down significantly on 2022, but the problem there is that it wasn’t enough. The consumer can purchase ready-to-drink vintages such as 2015, 2014, 2012, 2011, 2008, and 2006 for less.” Indeed, Matthew O’Connell, CEO of Bordeaux Index’s LiveTrade platform reminds me that “a headline discount on 2022 en primeur pricing is a somewhat meaningless number.”

Rather than labor over more data proving just how many times the golden en primeur pricing rule has been broken over the past decade, I would rather use the current situation—which is Bordeaux négociants at breaking point and en primeur sales fading into insignificance when compared to their former glory—as an opportunity to review the market for Bordeaux holistically and suggest that we, the wine trade, collectively ask ourselves how we got here.

The Bordeaux Buyers’ Club

Let’s take ourselves back to Bordeaux sales in the early 2000s. The formula was simple—access to fine wine as a symbol of success equaled buying Bordeaux en primeur. A generation of 30-to-40-somethings, with budding careers, homes whose prices were inflating beyond imagination post-purchase, and very comfortable disposable income had no qualms in investing each year for the promise of a fantastic cellar of mature claret tomorrow. After all, prices were “reasonable”—first growths sat at around or just over $100 a bottle—and Bordeaux with 10 to 20 years of age (from the 1990s or 1980s) for the odd bottle to drink immediately wouldn’t break the bank either.

The en primeur system was clever—it created an annual moment that any self-proclaiming “modern working man” would register in the years to come simply as the time of year to buy the next Bordeaux vintage. I imagine talk of the campaign during office coffee breaks wasn’t unusual—“Did you see Lafite out this morning? I bought a few cases”—and so the effect snowballed, beyond the planning of how much Bordeaux one might actually drink in a lifetime, beyond necessity, into the simple luxury of possession. Fast-forward 20 years, and the behavior of this same generation has not changed much, though prices have risen sharply, and now their cellars are feeling rather full. Since I began reviewing Bordeaux en primeur campaigns for The World of Fine Wine four years ago, I’ve made reference each year to the piling stocks of recent Bordeaux that don’t quite seem to stick in a forever home. The traditional Bordeaux en primeur buyer has either, rather sensibly, started to refuse allocations because he has enough wine, or has been buying only for speculation—because prices will always eventually rise, right?

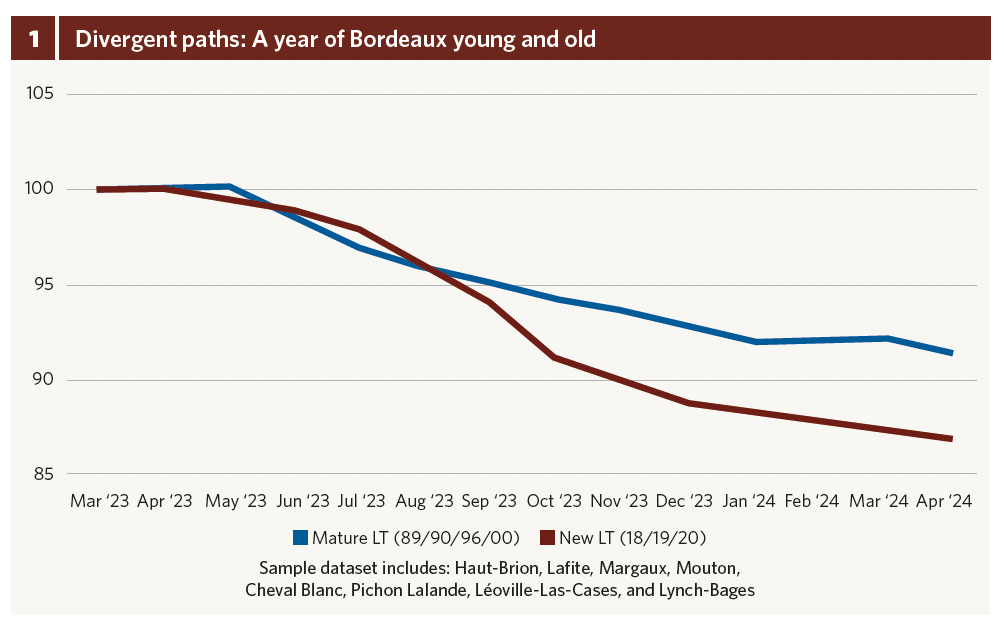

Right… unless an unprecedented economic blip intervenes, as it has post-Covid, when speculators have sought to liquidate assets in a big way, and troves of recent Bordeaux vintages (c.2016 onward) have reappeared out of private cellars onto the open market. It is completely logical that sellers of Bordeaux operate on a “last in, first out” basis. After all, mature Bordeaux is delicious, and though it might seem insensitive to suggest, many owners of recent Bordeaux vintages may not be around when these incredible wines—2016, 2018, 2019, 2020—finally reach their apogee. And so, amid a complex macro-economic environment, competition to sell these stocks has dragged prices down. The chart on the previous page shows the 12-month price performance of a subset of Bordeaux wines traded on Bordeaux Index’s LiveTrade platform. While sellers setting free their mature Bordeaux (represented by four vintages: 1989, 1990, 1996, and 2000) saw prices dip by 8% over the period, those liquidating younger vintages (2018, 2019, 2020) experienced reductions of 13% (fig. 1). What’s more, the mature-wines basket represents half the volume of, and 25% more in value than, the data set covering younger vintages.

The fundamental automatism of Bordeaux en primeur

While any die-hard Bordeaux lover like me might be rubbing their hands, snapping up any prized cases in this latest price fallout, the elephant in the room is impossible to ignore: Why aren’t there many more of us? The fundamental automatism of the en primeur system has left Bordeaux vulnerable to competition, especially among younger generations. While 20 years ago, buying fine wine was synonymous with buying Bordeaux (indeed, there was very little else with sufficient track record, proven quality, reliability, or renown), today fine wine has never been so eclectic. Burgundy, Champagne, Barolo, Brunello (to take only two countries)—the choices for extremely good wines are endless, and variety is actively promoted by a passionate industry whose members live for the discovery of what’s next.

Along the way, Bordeaux has continued to roll into the hands of so-called collectors, systematically purchasing en primeur on autopilot. But how many of these cases will be drunk by their original buyer? Sadly, I’d wager not many. Liv-ex’s market share by region makes Bordeaux’s shrinking position within an increasingly diversified market crystal clear. Twelve years ago, Bordeaux represented 87% of the fine-wine market (fig. 2). Today, that is reduced to just 38%, and at the height of fine wine’s latest price peak in 2022, Burgundy lagged behind Bordeaux by only 8%. Is this simply the natural result of widening tastes, or has Bordeaux’s selling system contributed to its relative popularity decline?

Hope springs internal

Bordeaux sales work within a B2B system. The négociants, whose international reach for distribution is nothing short of extraordinary, sell wine exclusively to other businesses. It’s no wonder Bordeaux has lost touch with today’s young wine consumers, when access to these people by those closest to the wine itself—the châteaux and their négociants—is limited, if not nonexistent. On the side of importers or merchants selling to final consumers, there are short-term motivators working against Bordeaux. First, the ease of selling high volumes of mid-priced Bordeaux to traditional Bordeaux buyers who don’t think twice about adding to their already abundant en primeur pile has, up until now, been beneficial to the bottom line. So is selling wine from Italy, Burgundy, or indeed anywhere else where a direct relationship with an estate equates to a margin of 30–40%, rather than the typical 10–20% achieved by selling Bordeaux. Within a fundamentally push-sell system, throwing diverse regional mud at the wall has seen almost everything but Bordeaux stick for those in the 30–40 age bracket.

There are several layers of sad irony in this phenomenon. First is that the fine-wine trade continues to love Bordeaux wines—perhaps so much so that we’re all keeping them a little too close to the chest (or more likely, that we underestimate the need for their promotion among younger drinkers). The second is that the Bordeaux châteaux operate based on multigenerational timeframes: These long-term business plans for production are not necessarily matched by marketing strategies of equal length or vision across the supply chain. And finally, with particular reference to the 2023 vintage, the viticultural and winemaking prowess in Bordeaux has never been as impressive as it is today—and yet the market continues to scream for lower prices. The latter fact, I imagine, has been especially hard to swallow for this latest vintage, after a vengeful Mother Nature threw all she could at the Bordeaux vignerons. Ultimately, however low the prices, marketing to today’s generation of 30-to-40-year-olds very good wines that won’t be available for two years—

and drinkable in 10, 15, or 20 years—is a very difficult job (especially when they can buy physical bottles from the same château for the same price or less).

Generation Now

And while other wine regions have found solutions to adapt access for millennials and Gen Zs seeking wine thrills in the immediate future, Bordeaux lags some way behind in this department. On a stylistic front, Bordeaux’s recent vintages—2018, 2019, 2020—may well be approachable sooner than vintages from a decade ago, but they will still be better with significant age. Even Bordeaux’s “second wines” are essentially too good, too complex, where a Bourgogne blanc or rouge is genuinely drinkable and delicious almost as soon as it is bottled.

Perhaps the recent resurfacing of Bordeaux from cellars fit to burst is a blessing in this regard. Mature wines

—or at least wines that are physical, with one or two years of age—are a tangible way for younger consumers to begin exploring a region that so deserves to be known and yet is perceived as being “old school” or “irrelevant” by so many Gen Zs. Indeed, the problem is certainly not the wines—it’s my firm belief that no other region in the world is capable (or indeed will ever be capable) of producing such consistent quality in such volumes, offered at attractive prices relative to the wider wine market. The problem is our method—sales via a B2B-focused system, and of wines that require literally decades of patience, without any immediate gratification relevant to today’s consumers (who care much less about what they own and more about what they experience). Appreciating fine wines today goes far wider than simply counting bottles in one’s storage account; it is animated by stories, social media, and experiences such as visiting vineyards.

Strategy transplant

Is it so crazy to consider that the system should change in order to adapt to today’s audience? Bordeaux châteaux were the first in the wine world with the foresight to keep back a portion of their production each year; can we not offer more of these to the young wealthy and curious collectors of today? Bordeaux Index organizes a tasting celebrating the Bordeaux vintage “10 years on” every year. Imagine if this were possible on a global scale, dictated and supported by the well-oiled Place de Bordeaux machine.

Today, the en primeur engine requires more fuel than anyone along the supply chain has currently got. First and foremost, the négociants cannot take another year of financial burden simply to “maintain allocations.” Any wines they confirm today are purchased with credit borrowed at a minimum of 4% interest, and the vast majority of Bordeaux 2023s will certainly not match the value appreciation in kind before bottling. Similarly, merchants and importers are creaking with Bordeaux—some of it strategic stocks, but most of it spilling from private cellars of those who have finally realized they own too much. And lastly, can we really ask millennials to look beyond the uncertain fog of today’s economic climate and shoulder the financing of a cellar they won’t touch for at least a decade? Mathematically, there’s no gain for the vast majority of wines released en primeur, especially when factoring in the cost of carry. Each year the number of wines falling under the “compelling buy” category for en primeur diminishes, and in 2023 (price-dependent of course) the list is particularly short—Ausone, Cheval Blanc, Les Carmes Haut-Brion, perhaps. Ultimately, a fact Stephen Browett was kind enough to share with me says it all: “En primeur is of declining interest to Farr Vintners. The 2009 vintage was around 50% of our turnover that year, but the 2022 vintage was less than 5%.” The proof is in the purchases (or lack thereof): Might there yet be a new dawn for Bordeaux en primeur? Or will this be the year it finally recedes into the twilight?