Château Magnol, formerly known as Château du Dehez, was one of many Bordeaux properties requisitioned by the Nazis during World War II. But, as documents discovered many years later revealed, the Cru Bourgeois property would go on to have a vital link to a daring 1942 mission against the Occupation undertaken by twelve brave Royal Marine volunteers.

Four densely written pages detail deliveries to Château du Dehez when under occupation by the German forces during World War II: 48 beds, 87 mattresses, 1,000kg of coal, equipment for installing window blinds and for repairing the roof of the château and its outbuildings, requests for the installation of additional toilets with running water and electricity.

They are recorded in a notebook that lay undisturbed for decades in the local town hall of Blanquefort, north of Bordeaux, and they form an ancillary to the original order to requisition the estate, delivered to Stéphane Cruse of 11 allées de Chartres on August 24, 1940. The Cruse family used Château du Dehez—identified as a cru bourgeois in the inaugural 1932 classification—as a hunting lodge, so it was occupied only during the occasional weekend, making it an easy target for the Germans.

The château was handed over to them almost exactly two months to the day from the signing of the armistice that saw France surrender to the Wehrmacht, with the victors dividing the country into occupied and non-occupied zones. Bordeaux, as a strategic target, was in the occupied zone, and Nazi troops reached the city on June 28, 1940. Within hours of arrival, the invading army had set up checkpoints, requisitioned homes, unfurled Nazi flags, taken control of the port, and set up gun emplacements. They would remain—both in the city and at Dehez—until August 28, 1944.

The town hall archives confirm that on the date of occupation, the château comprised 21 rooms in good state and a furnished three-room hunting lodge. An unsigned inventory details with great precision the crockery in the kitchen, the billiard table and its badly maintained cues, the Gaillard engravings on the walls, the Louis XIII bed and armoire in one of the bedrooms, among many other pieces of furniture, suggesting that the Cruses did not remove their valuables as many château owners did. In return, they were to receive a sum of 16,500 francs annually.

The documents are among dozens of similar records held in town halls all over the region. It is estimated that at least 100 Bordeaux châteaux were requisitioned by the Nazis, along with hundreds of other public and private buildings. But this one is exceptional in having a remarkable link to one of the most famed and daring missions of the war, carried out by a group of ten Royal Marines who risked their lives to paddle 70 miles (113km) up the heavily guarded Gironde River in collapsible canvas kayaks, on a mission to destroy enemy ships in a port protected by 10,000 German troops.

Château du Dehez becomes Kriegsmarine HQ

To understand why, just take a quick glance at a map of the region. The Germans were attracted to Bordeaux for the same reason that the Romans, the English, and dozens of other nations have been over the millennia—its strategic location on the Atlantic Coast, tucked away inland at just enough distance to provide safe harbor.

This made Bordeaux of enormous value to Berlin. Its deep port was perfect for launching and replenishing larger ships. The same features, however, meant it would also be a prime target for Royal Air Force bombs, so plans were drawn up to protect the all-important U-boats from attack. From 1941, work began on a submarine base in the Bassins à Flots area of the city, an inner harbor set back from the main river. This is where massive concrete pens—still intact today—would house the 12th flotilla of the Kriegsmarine, the German navy.

The colossal structure required 2,119,000 cu ft (60,000 cu m) of reinforced concrete, and took 6,500 forced laborers 19 months to complete, finally opening in 1943. As the works progressed, the Kriegsmarine moved into Château du Dehez, replacing the rank-and-file German soldiers who had been stationed at the estate for the first two years of the war. The move into Dehez was overseen by Admiral Erich Raeder, a key figure in Hitler’s inner circle, who led the Kriegsmarine until 1943, and who was directly responsible for the construction of the submarine pens. Lieutenant Colonel Klaus Scholtz became commander of the 12th flotilla.

From this point on, Dehez became their headquarters. Set back just over 2 miles (3.2km) from the banks of the Garonne River across wooded land, it was perfectly located for their requirements, allowing easy access to track ships coming to and from Bordeaux up to Verdon-Soulac at the mouth of the Gironde Estuary, as well as the railway from Le Verdon into Bordeaux that passed by this same spot. The location was less than 6 miles (9.6km) from the main port and submarine base.

To underscore its importance, Raeder made further alterations to the estate. A requisition order from the City Command dated October 1, 1942, orders a Pierre Tchernikoff, tenant of a farm on the Dehez land owned by Stéphane Cruse, to hand over to the German authorities the farm, along with all dependencies, parkland, stables, and other outbuildings. The land behind the château was used to build a Blockhaus measuring 98 x 49ft (30 x 15m), equipped with 6.5ft- (2m-) high doors at each end. Six rows measuring 49ft (15m) long and 14ft (4.3m) wide were built in the interior to store munitions, separated by cement walls with openings coiled in serpentine to protect against explosions. The Blockhaus was buried 6ft (1.85m) into the earth, with a total interior height of 8ft (2.43m). The primary use of this new building was for weapons storage, with a further bunker—which remains today one of the best-preserved in southwest France—designated as an air-raid shelter.

Operation Frankton: highly risky, if not insane

Over in Britain, meanwhile, at what was the lowest point of the war for the Allies, a plan was being laid. Earlier in 1942, Lord Selborne, minister of economic warfare, had approached Winston Churchill with an increasingly serious issue. A steady number of German ships were making it in and out of the port of Bordeaux, despite losses that had been inflicted on them by the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force.

Bordeaux had by this point become the main port for German ships traveling back and forth to Japan. Fast-moving blockade-runner ships and submarines were bringing in cargoes of rubber, rare metals, and other products essential for the German war effort plundered from newly captured Japanese territory in the Far East, and sending back machinery, weapons, and equipment needed for the aeronautical industry in Japan. At the same time, German U-boats were mounting a wide-ranging and deadly campaign sinking vital US ships supplying Britain with food and other necessities.

Churchill put Lord Mountbatten, chief of combined operations, and Anthony Eden, foreign secretary, in charge of finding a solution. The answer was far from simple. A large-scale naval operation was dismissed from the outset, because Britain simply didn’t have the boats to commit, and an aerial bombardment was seen as too risky to ordinary French lives, since the docks were so close to the center of Bordeaux city.

Instead, it was decided that a small group of commandos would launch a direct raid. It would become known as Operation Frankton, described by Mountbatten as a “brilliant little operation carried through with great determinism and courage” (and later by British MP and former soldier Paddy Ashdown as “a Whitehall cock-up of major proportions”).

A call was sent out for “volunteers for hazardous service,” who were “eager to engage the enemy,” “indifferent to personal safety,” and “free of strong family ties,” as a result of which, a total of 34 men were selected. A small unit was created known as the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment, overseen by charismatic commanding officer Herbert “Blondie” Hasler. They began four months of covert training for what they knew to be an extremely dangerous mission, but besides Hasler and his second-in-command at the time, none of them knew the destination or target in advance.

The original plan had 12 men in six kayaks (code-named “Cockles,” hence the Cockleshell Heroes) set off for Bordeaux. Each kayak was to carry two men, eight limpet mines, three sets of paddles, a compass, a depth-sounding reel, repair bag, torch, camouflage net, waterproof watch, two hand grenades, and rations and water for six days. Each man, the official files further detail, was also issued with a Colt .45 1911 semi-automatic pistol and a Fairbairn-Sykes fighting knife (commonly known as the British Commando knife).

On November 30, 1942, the group left Scotland in the submarine HMS Tuna, heading to Montalivet on the Atlantic coast. They arrived on Monday, December 7—by coincidence, the same day that Japan launched its attack on Pearl Harbor. As night fell, HMS Tuna rose to the surface to release the kayaks. During deployment, one boat was severely damaged, with a hole torn in its canvas side, rendering it unusable. William Ellery and Eric Fisher, the two men who had been due to use the kayak—named Cachalot—were ordered to remain behind, leaving just five kayaks and ten marines to undertake the mission. Those who went ahead, in order of entering the river, were: Major Hasler and Marine William “Bill” Sparks in Catfish, Lieutenant John Mackinnon and Marine James Conway in Cuttlefish, Corporal Albert Laver and Marine William Mills in Crayfish, Sergeant Samuel Wallace and Marine Robert Ewart in Coalfish, and Corporal George Sheard and Marine David Moffatt in Conger.

It was always a highly risky, if not outright insane, mission. Anyone who has seen the vast, swirling mud-filled mass of the Gironde Estuary would have some idea why. The Atlantic France pilot book published in 2023 by Nick Chavasse neatly sums it up: “Overfalls are severe and dangerous (5m [16.4ft]). Do not attempt to enter the estuary in strong winds from the SW through W to N if there is any swell or on the ebb tide. If in doubt, stand off… tidal streams are very strong and do not always follow the line of the estuary in the mouth; constant checks are required to avoid being set off the intended track.”

The plan for Operation Frankton was for the crews to paddle at nighttime, resting for five minutes in every hour, and to hide during daylight hours, making their way to the port in Bordeaux in an expected four to five days. After the destruction of the ships, the marines were then expected to travel on foot, undetected, across enemy territory, for 70 miles (113km) to meet up with the French Resistance and be taken to safety.

But to get there, they had to navigate, in the pitch-black and in the depths of a freezing winter, one of the most dangerous water courses of the Atlantic coast. Things almost immediately went wrong. Coalfish disappeared in the rough waters and rip tides at the entrance to the estuary. Crewmen Wallace and Ewart made it safely to shore near the Point de Grave lighthouse on the morning of December 8, but they stumbled directly into a Luftwaffe flak unit. The two British men were still in uniform and were promptly arrested. A little farther ahead, unable to navigate the meter-high waves, Conger also capsized, with crewmen Sheard and Moffatt scuttling their ship and swimming for shore. They never made it, both freezing to death in the currents of the Gironde.

Back in the Garonne, the three remaining kayaks continued. The entire river, which is several miles wide at this point, was heavily patrolled by German boats, with sentries and flak units at regular points. It wasn’t long before they came to a checkpoint with three German frigates. The men avoided detection by lying flat in their boats, and silently paddling, but Mackinnon and Conway in Cuttlefish became separated from the rest and were unable to continue. They safely reached the shore and set off for the agreed rendezvous point. Evading capture for four days, they made it as far as La Réole, around 40 miles (64km) to the south of Bordeaux, but were betrayed and handed over to the Germans.

The crews of Catfish and Crayfish—the only remaining kayaks—reached Bordeaux on the fifth night, December 11, when at last the river was flat-calm and the sky clear. The two boats split up, taking opposite sides of the river, with the attack starting at 9pm. Countless books, and one 1955 film, have captured the moment. Hasler and Sparks in Catfish, on the western side of the dock, placed eight limpet mines on four vessels, including a Sperrbrecher minesweeper. A sentry on the deck, apparently spotting something, shone his torch down toward the water, but the camouflaged kayak evaded detection. At the same time, Laver and Mills in Crayfish placed eight limpet mines on two boats, five on a large cargo ship and three on a small liner. All four men left the harbor by the early hours of December 12 and were safely out of the way by the time the first explosions took place at 7am that morning, destroying or disabling a total of six German ships, including the strategically critical blockade runner Tannenfels, which listed and then sank.

Captured Samuel Wallace, aged 29, and Robert Ewart, 21, who a few days earlier had been taken to Château du Dehez, wouldn’t learn of the success of the mission, but their silence under interrogation ensured it took place. Originally taken to the port of Royan on the Atlantic coast, they had been transferred to Dehez for interrogation by Admiral Julius Bachmann, the German flag officer in charge of western France, under the orders of Admiral Raeder.

In the months following the operation, the Germans’ official story was that all marines who died were found drowned in Bordeaux harbor. The truth was revealed in the early 1980s, when a new section of the German war archives was opened. At this point, the key role of Château du Dehez—by now renamed Château Magnol and owned by négociant Barton & Guestier—became clear. The archives showed that, besides Sheard and Moffatt, who did in fact drown in the Garonne, all captured marines were executed by firing squad under Hitler’s infamous Commando Order of October 18, 1942, which stated that, “From now on, all men operating against German troops in so-called commando raids in Europe or in Africa are to be annihilated to the last man. This is to be carried out whether they be soldiers in uniform, or saboteurs, with or without arms; and whether fighting or seeking to escape; and it is equally immaterial whether they come into action from ships or aircraft, or whether they land by parachute. Even if these individuals on discovery make obvious their intention of giving themselves up as prisoners, no pardon is on any account to be given.”

Wallace, who was born in Dublin and had been a marine for a decade by 1942, had joked a few days before the mission that if he were captured, he could claim neutrality as an Irishman; however, this order, in direct contravention of the Geneva Convention, changed everything. The two men were executed by a naval firing squad on the orders of Admiral Bachmann the night before their friends successfully placed their limpet mines. After two long days of interrogation, at no point did either man reveal any details of the plan. Instead, they claimed that they were traveling on a solo mission, or that they were sailors who had been swept overboard. The other four captured men would later withstand the same German tactics, with none revealing key details of the mission or the names of the French Resistance members who helped along the way.

The war diary of Admiral Bachmann for December 10, 1942, reads: “About 10:15. Telephone call from personal representative of the officer-in-charge of the security service in Paris, SS Obersturmführer Dr Schmidt, to flag officer-in-charge’s flag lieutenant, requesting postponement of the shooting, as interrogation had not been concluded. After consultation with the chief of operations staff, the security service had been directed to get approval direct from headquarters. 18:20. Security service, Bordeaux, requested security service authorities at Führer’s headquarters to postpone the shooting for three days. Interrogations continued for the time being.” The entry for the next day, December 11, 1942, changes tack: “Shooting of the two prisoners was carried out by a unit (strength 1/16) belonging to the naval officer in charge Bordeaux, in the presence of an officer of the security service, Bordeaux, on order of the Führer.”

The naval war staff had days earlier commented on their arrest: “The naval commander, west France, reports that during the course of the day explosives with magnets to stick on, mapping material dealing with the mouth of the Gironde, aerial photographs of the port installations at Bordeaux, camouflage material and food and water for several days were found. Attempts to salvage the canoe were unsuccessful. The naval commander, west France, has ordered that both soldiers be shot immediately for attempted sabotage if their interrogation, which has begun, confirms what has so far been discovered.” The execution almost certainly took place a short walk from Dehez, in a wooded area that is now a local technical college—a war crime against uniformed servicemen, for which the German officers would later answer during the Nuremberg Trials.

Of the four marines who successfully completed their mission, only two would make it back. Laver and Mills were arrested by the French police on December 14 and handed over to the Germans. Only Hasler and Sparks made it across the heavily guarded demarcation line into Free France, and were helped by the Resistance down to the Pyrenees and into Spain. Hasler made it back to England by military plane on April 3, 1943, while Sparks followed later by boat. For their part in the raid, Hasler was awarded a Distinguished Service Order and Sparks the Distinguished Service Medal.

Commemorated by Barton & Guestier to this day

Within months of the crucial archive discovery, Barton & Guestier held its first commemoration, on December 6, 1982, attended by representatives of the French Army and the Royal Marines—and by both Herbert Hasler and Bill Sparks. Hasler died five years later, in 1987, but Sparks returned in 1999, after the ceremony became an annual event from 1995. The 2002 ceremony, to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the mission, brought HRH the Duke of Kent (representing Queen Elizabeth II), Countess Patricia Mountbatten of Burma, daughter of Lord Mountbatten, and His Excellency John Holmes, the British ambassador to France, to Château Magnol. Sparks had passed away just a few days before the event.

Today you can find a Frankton memorial standing discreetly on the Bordeaux waterfront, and a commemorative plaque for Mackinnon and Conway in the town of La Réole. In Blanquefort, a tram stop that opened in recent years is named Frankton, while farther afield in the region, you can follow a 62-mile (100-km) commemorative walking trail tracing the route that the canoes took from the Atlantic to downtown Bordeaux.

At Château Magnol, the Blockhaus is today a wine cellar named Chai Germain Rambaud for the first cellar master at Barton & Guestier, who introduced the practice of fining wines with egg whites, a key step in the production of fine wines. A portrait from 1809, hanging in the main château, shows him in a smartly buttoned-up red jacket, carrying a candle next to a wooden barrel, ready to carry out his task of fining the wines.

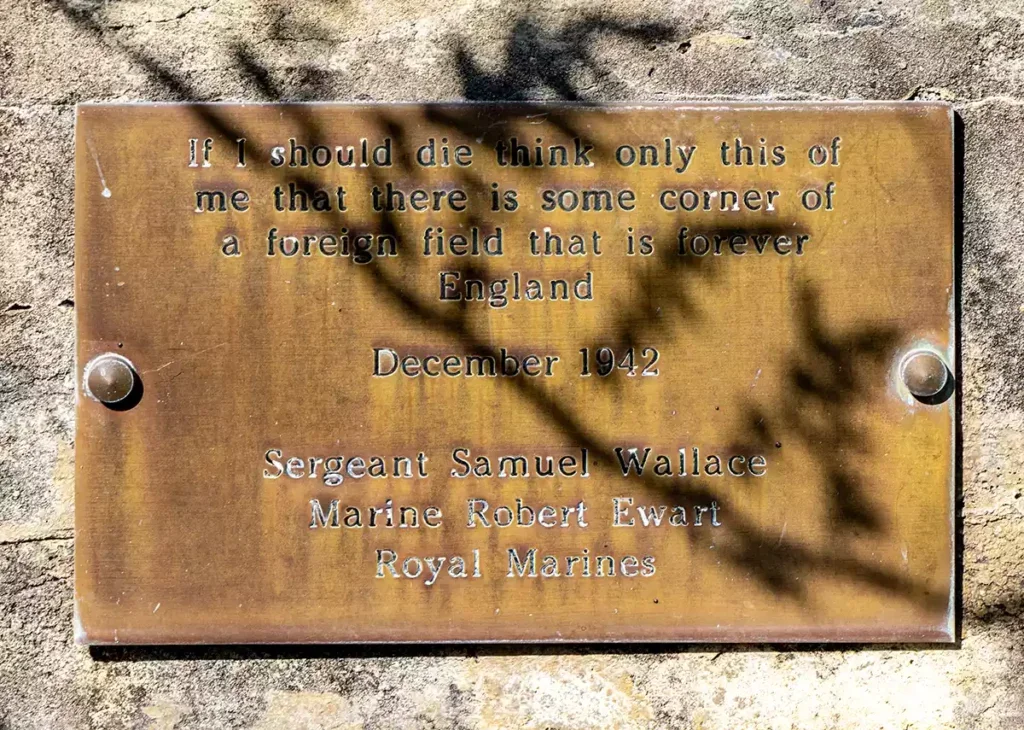

In the bunker itself, the serpentine walls are gone, with the cool underground cellar now housing tens of thousands of bottles of wine dating back to the early 1900s. A small memorial adjacent to the bunker stands in honor of the two heroes who fell nearby, with words from Rupert Brooke’s poem “The Soldier”:

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England.

December 1942

Sergeant Samuel Wallace

Marine Robert Ewart

Royal Marines

Notes

1. The original images used here were taken in 1969 by Peter Aaron, award-winning photographer and son of Sam Aaron of New York wine retailer Sherry-Lehmann. He had been sent to Bordeaux by Alexis Lichine for a book on the region that was never written. At the time, Seagrams was part-owner of Barton & Guestier—today the oldest wine merchant still in activity, with a long history of shipments to the United States beginning with a delivery to Baltimore in 1785. Peter Aaron returned to Bordeaux in 2024 to photograph the changes in the 55 years since his original visit, to be presented in an upcoming book authored by Jane Anson.

2. The author acknowledges with grateful thanks her debt to the book by Catherine Bret-Lépine and Henri Bret, Années Sombres à Blanquefort et dans Ses Environs 1939–1945 (Groupe d’Archéologie et d’Histoire de Blanquefort, 2009) and Yale Law School documents relating to Bachmann’s war diaries.