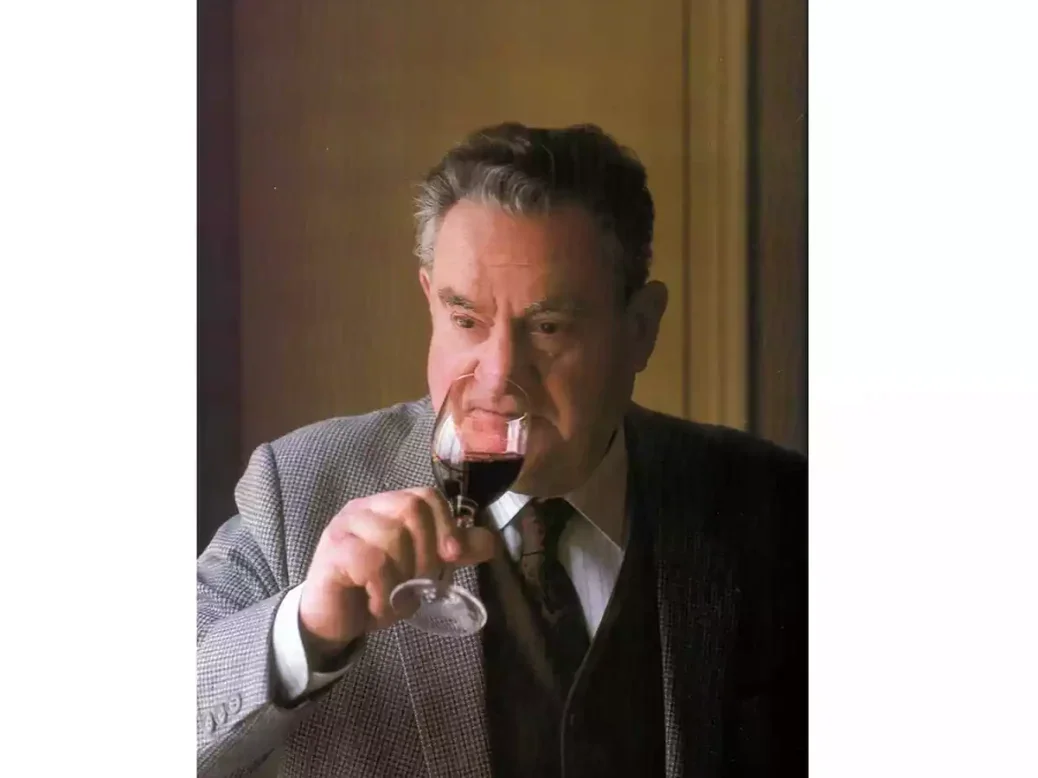

Professor Emile Peynaud, who died at the age of 93 in 2004, wrought enormous changes in the world of wine. It is hard to think of any other discipline in which one man exerted so much influence, writes Frank Ward. More than 20 years after his death, Peynaud’s influence is still very much with us, and to honor his legacy we share here a profile first published by Connoisseur magazine in May 1987.

A few decades ago, winemaking was still a hit-and-miss affair. Good wine often turned sour or fizzy without anybody knowing why. Professor Emile Peynaud, of Bordeaux, 75, not only helped find a cure to these complaints but at the same time turned winemaking into an exact science, without any loss of art. He, more than anybody else, has codified, clarified, and simplified the whole process. Because of him, Sherry and Champagne are purer, claret better balanced, Chianti more vinous, Chilean reds and New York State Chardonnays more characterful.

Though he retired officially in 1977, he goes on helping a dozen or more châteaux every year. His workplace is his study in a small villa in Talence, just south of Bordeaux. It is a simply furnished room, with a leather-topped desk, a marble floor, and glass-fronted bookcases. The professor wears a brown business suit and looks like a humane headmaster.

He is as much liked as he is respected. One château owner after another confesses that he owes “everything” to Professor Peynaud; they praise him for his kindness, sense of humor, thoughtfulness, lack of conceit, fantastic memory. Charging modest consultation fees for his services, he has transformed viticulture and viniculture in North and South America, revamped ancient winemaking techniques, created entirely new vineyards. A few years ago, he was simultaneously aiding three of the largest wine groups in the world, Suntory, Seagram, and Domecq. Of the crus classés of the Médoc, 45 use or have used his services, as have 11 of the 13 crus classés of the Graves and hundreds of châteaux in Pomerol, St-Emilion, Sauternes, and the lesser districts of Bordeaux. Before he came on the scene, many top châteaux made good wines only sporadically. With his help, their wine is now consistently great. He has performed miracles at châteaux Lafite, Margaux, Cheval Blanc, Léoville-Las-Cases, Pichon Lalande, and Lynch-Bages.

His effectiveness owes much to his breadth of vision and the catholicity of his taste. “I taste an enormous amount of wine,” says Peynaud, “and I’m very difficult, never satisfied. I can appreciate minor châteaux or the very great wines. What I look for is cleanness, purity of odors and flavors, and a certain personality.” Of his life’s work he comments, “I have been able to show producers that enology has its uses, that it can solve their problems and make their wines better—even the very finest. It’s a revolution that’s taken 30 years, the result of countless tests and experiments, of arduous work in the laboratory. I suppose I’m a unique case, because the circumstances that formed me will never be repeated. Besides, there’s less to change today; techniques are very advanced, and standards are higher.”

Strokes of good fortune and genius

Emile Peynaud was born in Bordeaux in 1912. His father died when he was 15, and he left school to support his mother and sister. By a happy chance he was taken on at the laboratory at Calvet, then Bordeaux’s leading wine shippers. While other bright boys were preparing for their degrees, starting with theory and graduating to practice, Emile Peynaud did the opposite. Luckily, Calvet let him study in the office of a professor of biochemistry: “The things I learned at Calvet could never have been picked up at a university.”

By a stroke of good fortune, his immediate chief at Calvet was Jean Ribéreau-Gayon, a brilliant chemical engineer only 22 years old, grandson of Ulysse Gayon, a pupil of Pasteur’s who founded the famous Station Oenologique of Bordeaux University. These two young geniuses were to change the world of wine drastically, working together in close and fruitful harmony for half a century. They studied the testing, analysis, stabilization, and clarification of wine and were soon finding cures for its various maladies. By 1936, Calvet asked Peynaud to supervise the vinification of a minor château in the Médoc—his first go at a skill that was to become one of his specialties. He had no overall strategy at that stage. “You find yourself solving one problem after another, making what seem to be minor discoveries. It’s only afterward you realize that some were really important. Discovery rarely comes as a great revelation. It’s making many small breakthroughs one by one.”

During World War II, he spent five years as a prisoner of war in Germany before being reunited with Ribéreau-Gayon in 1948. The older man was appointed head of the Station Oenologique in 1949, and Peynaud joined him there with the proviso that he would be free to act as an outside consultant. At the same time, he went ahead with his doctorate.

Hitherto they had concentrated on technical problems faced by a shipper. Now they turned to the crucial winemaking itself, as well as such related questions as piqure (sourness) and malolactic fermentation. Meantime, Peynaud was getting to know some château owners. “Bit by bit I began to penetrate a very closed society. I made friends with some of them and, even more important, with their cellar masters. They didn’t like me much to begin with,” he chuckles wryly, “but they came round when they started to see that I could explain things they hadn’t been able to understand. They also saw that I knew their métier better than they did, because of my practical experience at Calvet.”

By 1949, Emile Peynaud was helping a number of prestigious châteaux, while also assisting 45 small proprietors in the humble Premiers Côtes de Bordeaux. Michel Delon, of Château Léoville-Las-Cases, met with Peynaud that year. Beset with vinification problems, he had gone along to the Station Oenologique to get help, where he bumped into the professor. On hearing that fermentation at Las-Cases kept “sticking” (leaving the process incomplete), Peynaud pointed out that high temperature was at the root of the problem and that the must had to be cooled down. In those days, equipment for this did not exist, so he suggested a rough-and-ready solution. “He told me to take a thermometer off the wall,” says Delon, “attach it to a stick, and push it through the ‘cap’ of grape skins floating on top into the must. If the temperature got too high, I was to siphon the wine from the vat into small barrels and leave it to cool overnight. In this way, Las-Cases was the first château to cool down must scientifically.” Peynaud’s solution saved the wine.

The professor feels that his greatest single achievement is the series of discoveries he made in association with Ribéreau-Gayon about malolactic fermentation. The process, quite distinct from alcoholic fermentation, consists in the transforming of the powerful malic acid in new wine into mild lactic acid. Most wines benefit greatly from this big drop in acidity.

Peynaud’s ideas were scorned at first. Everyone insisted there was only one fermentation, the alcoholic, and that the “malo” (as they now call it) was a sickness that robbed the wine of the high acidity then thought essential for longevity. When, as often happened, wine refermented in bottle, microbes were blamed. Peynaud tried to explain that the wine must go through the “malo” if it were to become stable and balanced and age steadily and serenely. “To suggest that a second fermentation existed at all was a revolution against an article of faith. Going against the stream took a long time, and I had to win over the châteaux one by one with detailed explanations.”

The professor began holding free enology classes every Monday and kept them up for more than 20 years. One of his students in the early 1970s was Steven Spurrier, wine writer, leading wine merchant, and founder of the Académie du Vin in Paris. “The professor could make highly technical things seem simple, walking about the room like an actor, getting people’s brains working. He had a striking way of putting things, and they suddenly became plain. He had great knowledge and enthusiasm, reducing wine to simple terms.”

He helped more and more proprietors, often waiving a fee, leading a team of eight researchers at the Station Oenologique and writing books, bulletins, and articles. With Ribéreau-Gayon he wrote the major textbook Traité d’Oenologie and has since written Knowing and Making Wine (available in English) and Le Goût du Vin (translated into English by Michael Schuster as The Taste of Wine), a modern counterpart to Brillat-Savarin’s classic The Physiology of Taste.

Michel Delon celebrated the tenth anniversary of his first meeting with the professor by calling him in at Las-Cases. For some years the wine had lacked color, depth, and body, largely because of a vatting time (for the fermentation and maceration of the crushed grapes) of only ten days. Peynaud upped this to three weeks and suggested other changes. The 1959 wine, the first made with his help, turned out splendidly. Today, 28 years later, it is concentrated and vigorous, with balance and power to ensure at least 15 years of further improvement.

In the late 1950s he helped the Champagne house of Mercier with technical problems. This assignment was an eye-opener. The slow, clean, very cool fermentation used for making Champagne conserved the wine’s subtlest and most delicate aromas and flavors and would therefore be perfect, he saw in a flash, for all kinds of dry white wines. He introduced it in Bordeaux, and it was a huge success. Today it is used all over the world.

His next client was Nicolas, the giant Paris wine merchants. First, he helped them improve stabilization and bottling techniques for their one-liter bottles of cheap Midi reds; then he somehow prevailed upon the peasant growers to allow their thin, acidic wine to undergo the malolactic fermentation and become rounder, fuller, and fresher.

Broader horizons and an enduring legacy

The professor began to feel a need for broader horizons and new perspectives. “If you stay on home ground, you never learn anything new. I came to see that if I wanted a better understanding of winemaking in Bordeaux, I needed to know about vinification in other regions.”

So began many years of foreign travel that took him to North and South America, Greece, Spain, Italy, and elsewhere. In Spain, he became a consultant to several leading Rioja firms. “Spanish wines are of very high quality and cost only a third as much as French. Spain could produce great wine, but first she must modify her viticulture. The trade is dominated by shippers, who blend or make the wine from too many disparate elements.”

In Italy he helped Gancia with sparkling wines and Antinori to develop Tignanello, in which traditional Chianti grapes receive extra vinosity and complexity through the addition of Cabernet Sauvignon. In Greece he supervised the creation of Château Carras, a Balkan “Médoc” made from a mix of native Greek and noble French varieties. “I learned more from working outside France than I did inside,” he recalls. “I discovered that many countries were much better equipped than we were, with our antiquated installations. Some wineries in Spain are far better equipped than, say, Château Margaux!” Lessons learned abroad made him a keen advocate of stainless-steel equipment.

Although Peynaud’s influence on winemaking in the Médoc goes back to the late 1930s, with his explanation of malolactic fermentation, the real breakthrough came in the 1960s, when a growing number of château owners adopted his methods. It was the first of many breakthroughs. His next step was to get château owners to harvest much later than usual, giving grapes time to ripen fully, then picking rapidly while they were still fresh and healthy. Under his influence, Bordeaux now harvests eight to ten days later than before the war, and picking is completed in ten to fourteen days instead of three weeks. The result is astonishing. Claret made from wholly mature grapes has a deeper and more lustrous color, richer scent, more concentrated flavor, more roundness, and better balance. The tannins in fully ripe fruits are softer and the wines can be drunk younger, though they still age extremely well: “The wines we make today will outlive the corks.”

The date of the harvest is fixed scientifically, and the grapes are selected with unprecedented care. Quality control starts in the vineyards, where underripe or rotten bunches are left on the vines. “Grapes not ripe enough to eat aren’t fit for winemaking,” says Peynaud. At properties where his advice is punctiliously followed, like Château Margaux, the grapes are sorted yet again inside the winery.

Selection has only begun. Most fine vineyards comprise parcels of land, each with its unique geology and exposure, each giving noticeably different wine. The professor sees to it that grapes from each parcel are vinified separately. Different grape varieties are kept separate too, as are grapes from old and young vines. Every single vat is vinified individually, depending on its contents. “At Margaux, I taste every vat several times a week. I might say, ‘This one isn’t bad but isn’t tannic enough yet. Let’s leave it a day or two. But this one has enough tannin. It’s time to run it off.’’’ In effect, grape skins are infused in grape juice like tea leaves in hot water. The longer the vatting, the more color, flavor, and tannin will leach out from the skins. This gives the winemaker the freedom to make the style of wine he wants. In general, the professor vats a classified Médoc longer than a petit château, and a powerful premier cru longer than a light quatrième. Better a wine too fruity than too hard, for if it lacks backbone, the professor advises adding extra tannin and “extract” with vin de presse, dense essence obtained by a last pressing of the skins.

The final quality control occurs when the vats are tasted in the spring. Only the very best is blended to make the grand vin sold under the château label; the rest is either released as generic wine or marketed as the château’s second wine. At Margaux, between 20% and 40% of all wine legally entitled to carry the name is used instead to make a second wine, Pavillon Rouge. The result is a grand vin much finer than it would otherwise be, and a second wine, excellent and inexpensive.

Some critics suggest that wine made in the Peynaud style is stereotyped. True, all have excellent color, optimal balance, and pronounced varietal character—traits without which no wine can be great. “The wines of yesterday were more stereotyped than today’s,” says Peynaud. “They were all similar because they shared the same defect. They were oxidized.”

Today the professor is involved in the creation of a potentially great new vineyard at Château Clarke on the site of a defunct one. At Château Lagrange, in St-Julien, he has had a rundown winery and estate totally refurbished, with heated flooring and modern stainless equipment within and major replanting without. But his special pride is Château Margaux, the majestic premier cru, which he has transformed. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the château was badly neglected and the wine below par. It was bought in 1977 by the late André Mentzelopoulos, owner of a grocery chain, who called in Peynaud. Philippe de Rothschild, owner of Château Mouton Rothschild, warned the new owners that it would take ten years to regain former glories. “We did it in one year,” says the professor proudly. The 1978 Margaux is hailed as one of the finest Médocs in that very good vintage.

André’s daughter, Corinne Petit-Mentzelopoulos, is in charge at Margaux today. “It’s the professor who makes the wine, and our success is due to him. He doesn’t talk much, but when he does, it’s to the point. He remembers every vat out of scores. I’m always amazed when he comes at harvest time after tasting hundreds of other wines and says, ‘Can I taste vat number three?’ He can tell the Margaux team what to do, but he can’t be around to see they do it. Yet such is his authority and tact that they do as he says. His great value is shown by the wine we make today.”

The last time I saw the professor was in the Médoc when we were both lunch guests of Michel Delon at Léoville-Las-Cases. We began most auspiciously with a tasting of ten consecutive vintages of Las-Cases, from 1984 back to 1975. All had been made with the professor’s help. Frowning, he sniffed at his glass. “The ’83 is still a bit rough; it hasn’t started developing bouquet yet. We ought perhaps to bottle it in May. The ’82 is already very aimable, with the same power as the ’83 but more amplitude. Quel joli quatre-vingt! [What a pretty 1980!] Not quite ready to drink yet, though.”

After lunch, in a private room at a nearby bistro, the professor was induced to talk about his favorite Médocs, some of which, he said, refuse to conform to their reputed styles. “The soil transcends the appellation,” he said in his gravelly voice. “People think that Margaux is chiefly about finesse and stress the wine’s floweriness and delicacy. It is indeed rich in both of those qualities, but in fact the château, in terms of structure, is really more like a Pauillac than a Margaux and is one of the most tannic of all Médocs. La Lagune is in the Médoc but has the character of a Graves. Lafite, a Pauillac, is more like a St-Julien. Las-Cases, here in St-Julien, is really a Pauillac, a kind of light Latour; and Beychevelle, nearby, is light and supple, very different.” He smiled, enjoying these vinous paradoxes.

Finally, relaxed and expansive, among friends, he talked freely on many subjects. He does not worry that no one will continue his work; he has trained some 1,500 enologists. Nor has he ever wished for his own vineyard. “I have the pleasure and the privilege of making such wines as Margaux, Las-Cases, and Lafite—what property could I ever own where I could make such wines as these?” On the other hand, he would dearly love to make a “super-Médoc” from the very choicest vats of Château Latour, Mouton Rothschild, Lafite, and Margaux. “I could make a wine that would be superior to and more complete than all the premiers crus.”

Michel Delon stared at him. “A super-Médoc? What would you call it?” The professor chuckled. “Philippe de Rothschild and Robert Mondavi called their Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon ‘Opus One.’ Why not ‘Opus Two’?”

Fancy or not, it would be fitting if this man, who has transformed the wine drunk by millions all over the world, had the chance to choose a cask each of the premiers crus of the Médoc and see what he could come up with. It could well be the greatest wine ever made.