In 1912, during the foundational years of the science of psychoanalysis, its leading light Sigmund Freud wrote a short essay with the unsettling title, “On the Universal Tendency to Debasement in the Sphere of Love.”1

Freud’s aim was to question why there appeared to be something in the nature of the sexual instinct that made it inhospitable to the ideal of comprehensive satisfaction. Where obstacles were placed in its way, by the social mores of the day, through lack of opportunity or as a voluntary practice of self-denial in the case of monks and other ascetics, the instinct thrived, positively gushed forth indeed, through its negation. When the bar to its expression was lifted, however, as in the conduct of marriage, the libidinal instinct was so often found to wither.

It was the sort of argument that gave medical psychology a scent of scandal in late Habsburg Vienna. In the middle of the argument, though, Freud offers a suggestive analogy. “Consider,” he proposes, “the relation of a drinker to wine.” Does not the daily intake of wine always give its consumer the same “toxic satisfaction,” without the need to put any impediment in its way? He makes a gestural reference to the conventional metaphoric homology drawn by poets between inebriation and erotic pleasure, and states, without adducing any evidence, that this is supported by science too. He suggests that nobody has ever heard of a drinker needing to vary his chosen tipple regularly to keep from becoming jaded with it, and the idea that one might throw obstacles in one’s way by travelling to a country where alcohol was prohibitively expensive, or prohibited altogether, is manifestly absurd. If drinking and sex offer the same kind of enjoyment, Freud postulates, “[w]hy is the relation of the lover to his sexual object so very different?”

Obstacles on the path to pleasure

And yet it is, he goes on to show. Rather than follow him along that path, however, it is worth asking whether his observations about the drinker’s relation to wine hold water, either then or in our own time. Today, when the practice of drinking has been subjected to widespread medicalizing, the path to its enjoyment is encumbered with nothing but obstacles. The need to count one’s weekly intake in globally variable units is incumbent on all, while the occasional requirement to report it to medical professionals has produced a generation adept in imaginative fiction. Wine, sometimes valorized as the healthiest form of intoxicating drink, is no more exempted from these procedures than is value-brand vodka. On Freud’s analogy, this should have no effect on people’s delight in drinking, and an unscientific survey of the evidence during a Friday night on the town seems to bear him out.

His first point, though, is a different matter. “Has one ever heard of the drinker being obliged constantly to change his drink because he soon grows tired of keeping to the same one?” Nothing stales the finite variety of a nightly diet of beer, to be sure. But recall that his paradigm drinker’s choice is wine. Nothing about wine stays the same. It is made all over the world—or all over Europe at least, as far as the Viennese wine trade was concerned. Even wine from the same appellation varied from one vintage to the next. Even bottles of the same wine in the same vintage changed according to when they were drunk, or where they had been stored, or how much air they had been exposed to before they were poured. Wine is intrinsically variable. Its sameness as a consumption practice is not an impediment. because it isn’t sameness in the same way as the invariability of beers and spirits is.

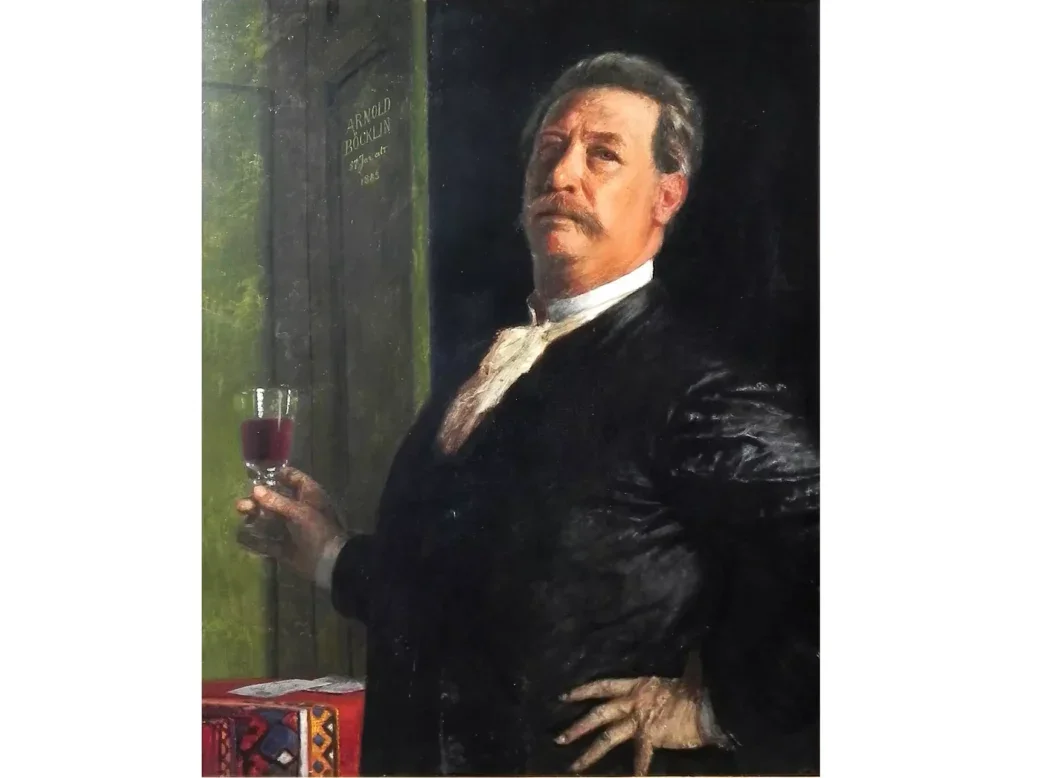

In other words, when it comes to wine, this is an argument from false premises. Before he moves on from it, Freud makes another illustrative point. “If we listen to what our great alcoholics, such as [the Swiss painter Arnold] Böcklin, say about their relation to wine, it sounds like the most perfect harmony, a model of a happy marriage.” That would be one, not particularly convincing, characterization of alcohol disorder, but his exemplification of Böcklin is not intended to suggest any pathology. Instead, the painter, though held to typify one of “unserer grossen Alkoholiker,” is actually being asked to play the role simply of a great drinker.

I confess I have no idea whether Böcklin drank the same wine night after night, or preferred to ring the changes, but the notion that voluminous ingestion of wine involves no variation is, to say the least, a little slapdash. Like much else, it was roughcast applied to the exterior walls of Freudian speculation. At this formative period, psychoanalysis was one of the dynamic intellectual movements of a great dynamic culture, in which the gear systems of the 19th century had begun to grind and shift. All the old certitudes were fair game. It would take another century before the understanding of the culture of wine consumption began to be susceptible of more nuanced thinking than this. For the time being, to Freud, it didn’t much matter.

- In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (1999), ed. James Strachey, 11: 179-190. ↩︎