Alex Maltman explores the wonderfully varied geology along the length of the River Loire.

Golden eagles and vultures soar overhead, while roaming down in the forests are wild boar, wolves, and, by some accounts, lynx. This is the Cévennes, one of France’s wildest and least populated regions, with the darkest of night skies. It is fitting, then, that from here flows France’s wildest major river, the Loire, barely navigable for parts of its 625-mile (1,006km) course. But ironic that farther downstream it acquires the sobriquet “royal” and glides past celebrated châteaux.

It’s a contrast further reflected by the wonderfully varied geology of the vineyards along the entire length of the river and the astonishing diversity of their wines. In this article, I will follow the geology of the river’s long journey, with pauses for a little more detail on some of the vineyard areas—geological vignettes, so to speak, of a regal river.

The Loire: A river is born

Volcanic hills, geologically young, dot the Cévennes landscape. One of them, Mont Gerbier de Jonc, is unusual in both its rock composition (technically, a phonolite) and its being crisscrossed by cracks and narrow fissures. These allow the winter’s rainwaters to percolate down until they meet old granite-like rocks below, part of what geologists loosely call the “crystalline basement.” The waters can descend no farther, so they seep sideways until they eventually emerge at the foot of the mountain as a series of springs.

It’s the coalescence of these springs that forms the nascent Loire. Crystalline-basement rocks are thus instrumental in spawning the river, and, as it happens, it’s basement rocks that floor the Loire in its very final stages, as it meets the Atlantic Ocean near Nantes.

Curiously, the infant Loire leaves Mont Gerbier southward, flowing toward the Mediterranean for a brief eight miles or so (13km), before swinging abruptly northward and starting to head for the North Atlantic. This is the result of forces within the Earth that rippled out from the rising Alps and uplifted land to form the Massif Central. They caused land surfaces in the Cévennes to tilt, compelling several rivers to readjust their courses. In fact, the Loire has changed its course several times in prehistory, at one time joining the Seine to reach up to the English Channel.

These same land adjustments led rivers to cut down deeply, generating the spectacular gorges that we now see in the Cévennes region. They also gave an overall northward tilting that has led to most of the major tributaries of the Loire—the Allier, Cher, Indre, and others—joining from the south. The land continues to readjust even today: Entire portions of the Loire Valley are rising while others sink, albeit at rates less than an imperceptible millimeter a year. (Trivial though that sounds, if that movement were to continue uninterrupted for a million years, the land surface would have changed by a kilometer!)

Côtes du Forez

The first wine region of note on the Loire’s journey is somewhat enigmatic, little known, and short on identity. It’s mainly on the slopes of the Côtes du Forez, 10 miles (16km) or so west across the plain from the river itself. Although it’s an AOC region, it’s often overlooked; some of the books I have on French wines don’t even give it a mention. Worse than that, just three decades ago, one respected critic was calling Côtes du Forez wines “rubbery and tasting of boiled sweets,” “inky and farmyardy.” Great improvements have been made since then, but the region is still searching for an image.

The soils here are very largely derived from the granitic bedrock that underlies the forested hills. Consequently, Côtes du Forez, with its traditional Gamay grape variety and carbonic maceration, was traditionally positioned as something of an alternative to Beaujolais. This tactic failed to work, though, and over time the area under vines has dwindled. Perhaps more productive are the patches of basalt and related rocks in the area, localized effusions of the lava associated with the much grander affairs of the Auvergne volcanoes. This has been enough, with the recent fashion for so-called “volcanic wines,” for some producers to form an association to promote themselves as Loire Volcanique.

The granitic bedrock is itself a complex business—part of, but not identical to, the crystalline basement at the Loire’s source. These so-called basement rocks are the geological foundation of all of France: Billions of years of Earth processes have produced rocks that are strikingly crystalline, with well-formed minerals glinting in the sun. Upon them were deposited the sedimentary rocks with which we are more familiar: limestones, sandstones, and the rest, with volcanic deposits in places.

Granite in these basement rocks will have solidified from molten rock, itself formed deep in the hot Earth from the melting of preexisting rocks. Sometimes the melting was incomplete, such that if this material eventually found its way to the Earth’s surface, we would see a melted and unmelted mixture. Such a rock is properly called a migmatite, from the Greek for “mixture”. It’s a common bedrock in the Côtes du Forez, along with granite, and it appears on several wine names in the area. Both of these rocks weather to give pale-colored, sandy, well-drained soils.

Despite past condemnations of this area’s wines, there are current lists describing them as “incredibly delicious” and “intoxicating and sumptuous.” Some growers are now experimenting with new methodologies and trialing cultivars that may be better suited to these soils. Might Côtes du Forez be about to emerge from its past shadows to join the bright stars of the Loire firmament?

Where the Loire river grows

Down on the plain below the Côtes du Forez, the Loire is strengthened near Nevers as it is joined by the Allier. The newly enlarged river lays down broad spreads of sands and gravels, and as it continues northward, it eventually encounters the sedimentary strata that will underlie its bed for the next several hundred kilometers. The crystalline basement is still there but is now buried a kilometer or more below these younger rocks.

These younger strata came about around 200 million years ago, when the part of Earth’s crust that was to become the North American continent was separating away from Europe, to create the Atlantic Ocean. Hereabouts in Europe, the land sagged such that the sea was able to move in: warm, sunlit waters, rich in aquatic life. In the times that followed—first, during what geologists refer to as the Triassic Period; then, the Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Tertiary—the extent of the sea varied; waters were sometimes deeper, and at other times shallow enough for reefs, lagoons, and tidal flats to form. Through time, a wide range of strata including shales, sandstones, limestones, and marls—some rich in fossils—were deposited on the sea floor.

Then, roughly 100 million years ago, the sea started to recede as the region was gradually uplifted by those same Earth stresses that created the Massif Central and the Cévennes. The strata were gently flexed into a broad saucer shape, with the youngest strata in the central part, more or less centered on present-day Paris, which is why the arrangement is referred to as the “Paris Basin.”

The first of these rocks that the Loire meets are Middle Jurassic in age (around 150 million years old), at about 7 miles (11km) south of La Charité. Then, by the time the river reaches La Charité itself, it’s crossing Upper Jurassic strata, including, farther downstream at Pouilly, rocks of the famous Kimmeridgian and Portlandian subdivisions. By the time the river reaches the Coteaux du Giennois, the strata are yet younger (Cretaceous age; around 100 million years) and farther on, in the Orléans wine district, the bedrock is largely of Tertiary age, some of it less than 20 million years old. From then on, the geological ages reverse as the river continues westward and encounters progressively older strata toward the western edge of the Paris Basin.

Of course, in detail, things are much more complicated than this, not least due to localized geological faults having shifted the strata. A pronounced example is at Sancerre, where to the west of the river, the Upper Jurassic bedrock has been displaced downward between several north–south fractures. But curiously, the down-dropped, originally higher rocks of Cretaceous age, are tougher—famously flinty—and have resisted erosion. Thus, they now form higher land, such as the prominent butte on which the town of Sancerre sits. Similar tough rocks cap the hill of St-Andelain, over on the Pouilly side of the river, giving an island of younger (Cretaceous) bedrock surrounded by older (Jurassic) materials. The traditional belief is that these intricately differing rocks have a profound effect on the resulting wines.

The regional uplifts and tilting of the land surface become apparent again at Orléans, where the river abandons its northward trend toward the English Channel and swings westward, approaching the renowned wine district of Touraine. Here, as one example of the kind of geology in this area, I focus on one of the lesser-known districts, the AOC Touraine Azay-le-Rideau, between the south bank of the Loire and its tributary, the Indre.

Azay-le-Rideau

In 1883, local doctor Monsieur Deschand decided to plant vines just east of the village of Azay-le-Rideau, on the banks of the Indre. While digging, he stumbled across a cache of several hundred beautifully cast weapons and tools dating from the Bronze Age. And in a nearby vineyard, in 1906, an ancient sarcophagus was unearthed, containing numerous funerary objects and, touchingly, the skeleton of a child clutching a coin, presumably ready to pay the ferryman to cross the Styx into the underworld.

These are just two glimpses of the long human history of the Azay-le-Rideau area—a history that includes winemaking. A winepress dating from as long ago as the 2nd century was discovered at Baigneux, to the south of Azay-le-Rideau; and in the church of St-Martin in Lignières-de-Touraine, to the northwest, a 13th-century fresco portrays a vigneron happily harvesting his grapes and treading them in a wooden vat.

Even so, Monsieur Deschand was taking a risk planting vines. The history of winemaking in the district had distinctly fluctuated in success, and 1883 was the very time that the dreaded phylloxera was arriving in Touraine. As it turned out, nearly half of the Azay-le-Rideau vineyard area was to be lost to the disease.

But what of the geology in all this? In some ways, it seems of little relevance. One published study ranked the factors that appear to have influenced the Azay vineyards over time: While things like changes in the local population, drinking habits, and transport availability were all significant, the role of the soils here was deemed “rather weak.” And the soils, mostly derived from calcareous Paris Basin strata of Late Cretaceous age, are still largely ignored by today’s growers. Limestone soils that elsewhere might be much esteemed here lack vineyards altogether. Yet there are poorly drained clay soils, a priori unfavorable to viticulture, that have vines.

Most of the vineyards are located on the slightly elevated plateau between the Indre and Loire rivers, probably because of its advantageous mesoclimate. The soils there are largely stony clays picturesquely known as perrouches (literally, “parakeets”). Also up on this plateau area are rocks and soils with another intriguing name: poudingues. The English translation is “puddingstone,” which is the original name for such pebbly material in England, supposedly for its mottled look, similar to an old-fashioned Christmas plum pudding. In England the rock name came to be replaced by “conglomerate,” but it seems that the original moniker sneaked across the Channel to be absorbed into French.

In a subtle way, though, the geology is crucial for the wine here—at least in terms of its image. For the vast majority of people, the name Azay-le-Rideau means one thing: the celebrated Renaissance château. It’s why more than 95% of visitors come here. As with the other great châteaux of the region, Azay-le-Rideau is constructed from the illustrious Touraine bedrock tuffeau blanc, so suited for these kinds of splendid buildings. This limestone-like rock is somewhat sandy and very porous, easy to extract and shape, and it weathers to give soils well suited to viticulture. Hence, numerous Touraine wines have “Tuffeau” in their names and on their labels: The châteaux and the stone of their walls have become inextricably linked with the region’s wines.

In fact, the bedrock at Azay-le-Rideau itself consists of strata overlying the tuffeau blanc. It’s still referred to as tuffeau, but it contains a potassium/iron-rich mineral called glauconite, which weathers to give the rock a yellow, ocherous look—hence tuffeau jaune. It lacks the desirable, fabric-like sheen of tuffeau blanc, so it is used largely for the lesser buildings of the area.

The high porosity of tuffeau blanc makes it soft and easy to work, which is a great advantage for building. However, that same porosity induces the stone to store moisture, accelerating its weathering. As a result, a number of the Loire châteaux—including Azay-le-Rideau—are now decaying nastily, and intensive research is underway on how best to conserve their walls while preserving their characteristic velvety texture.

The Azay-le-Rideau vineyards were included in the 1939 AOC Touraine appellation, and in 1953 the district was allowed to append its own name, too. Whether or not this has been beneficial is much debated. One can only speculate how many of the 300,000+ visitors to the Azay-le-Rideau château are tempted to buy the district’s wines because of the attached name. Perhaps some are, and there are certainly now a few enterprising producers attempting to raise the area’s profile, but the fact is that the area under vine continues to shrink. Despite the imposing name it can now use, the Azay-le-Rideau vineyard area is today only about one tenth of what it was when Monsieur Deschand was planting his vines.

On to Anjou

A few kilometers downstream from Azay-le-Rideau, the Indre joins the Loire. By now, the Loire is broad and distinctly braided by sandbars and spits as it flows languidly westward, to leave Touraine and enter the Saumurois. The river is flanked by broad swaths of modern alluvium, especially to its north, but the bedrock remains largely Late Cretaceous calcareous rocks with some sandstone. These underlie the vineyards all around. The wines, of course, cover the gamut from red to white, dry to sweet, still to sparkling. The local sandstone is visible in the immense Dolmen of Bagneux near Saumur, the largest in Europe, but the most conspicuous rock is still the tuffeau blanc. It’s in the walls of the local houses, bridges, the stately castle of Saumur itself, and in the bluffs along the Loire’s south bank, riddled with troglodytic caves hosting mushrooms, tourist accommodations, and innumerable bottles of wine.

Then, a few kilometers beyond all this, the Loire passes imperceptibly into the region of Anjou, also heavy with wines of assorted colors and levels of sweetness. Most of the great Renaissance châteaux are now left behind, but the river’s regal sweep continues, crossing the heartland of an empire that once stretched from the Pyrenees up to northernmost England. At first, the bedrock is still the sedimentary strata of the Paris Basin—sandstones, limestones, and the like. Their pale color gives the district its sometime sobriquet L’Anjou Blanc.

However, the strata are close to the very western edge of the Paris Basin’s “saucer,” far from the thick deposits that accumulated in its center, and so they are becoming progressively thinner. Erosion has inexorably been stripping away the layers, such that there comes a point in the river’s westward course where they are no longer there. At the little village of La Daguenière, about 4 miles (6km) east of Angers, the crystalline basement, which has remained at depth ever since the river left the Massif Central, is once again at the surface, once again visible. The rocks are highly varied but overall somewhat dark in color. We have entered L’Anjou Noir.

Anjou is centered on the historic city of Angers, just north of the Loire itself, on the Maine River (an unusual case of a tributary coming in from the north). The district’s bisected geology is reflected in the city’s dual names: sometimes Angers la Blanche, from the pale tuffeau walls of its old buildings; other times La Ville Noire, because of the roofs built with the local black slate—Angers was once one of the world’s great slate-producing sites.

Slates are, by definition, fine-grained rocks that split cleanly, but those at Anjou are exceptionally fine and can be formed into unusually small and thin plates. As a roofing material, they allow for intricate shapes and patterns—such as the elaborate curving roofs and turrets that feature on all the Loire châteaux. The 2014 decision to close the Angers mine was tragic—it ended a tradition that had started as long ago as the 6th century. And it was something of a blow to France’s patrimonie, given that roof repairs to the celebrated châteaux now have to use slates imported from Galicia in Spain.

The slates at Anjou are just one example of the multifarious rocks that stretch westward from here as part of the crystalline basement, here termed the Armorican Massif. As we saw in the Massif Central, this “basement” is an amalgam of ancient rocks and geological processes that came to an end around 300 million years ago. In fact, the Armorican Massif is characterized by this antiquity of bedrock rather than by being physically higher. Uninterrupted erosion has reduced this region to an irregular low plain, mostly no more than 160ft (50m) or so in altitude. But some of the rocks here are exceedingly ancient: At Brittany’s Locquirec (Finistère) and Trébeurden (Côtes-d’Armor) are the oldest rocks in the whole of France, formed at least 2 billion years ago.

The kinds of rock are dazzlingly diverse. It strikes me that some wine commentators love to use geological terms, and (seemingly) the more technical, the better. The Armorican Massif provides rich pickings. To illustrate, I will focus on Savennierès, one area from this part of the Loire.

Savennierès: On the north bank of the Loire

“Like a child’s paint box,” wrote one commentator when describing the soils at Domaine du Closel, in the heart of the little village of Savennières, on the Loire’s north bank. The visual effect might have something to do with the limpid luminosity of the river, which master of light JMW Turner attempted to capture in 1826, but it’s the assortment of differently colored pebbles that catches the eye. The Savennières AOC stretches westward of Angers, over hills and valleys that are at right angles to the river. And it’s particularly at the foot of some of the slopes that fragments of all sorts of rocks have come together.

Some of the pale, shapeless pieces aren’t really rock at all, but soft clods of the windblown sand that clothes the hilltops. Other pale materials are sandstones and jagged hard rhyolite, a rock exactly like granite except that it is fine-grained, usually because its parent molten material was chilled at the Earth’s surface rather than slowly cooling at depth. Another fine-grained, chilled material seen here is spilite, a sodium-enhanced variety of the dark-colored rock basalt. Typically, the quenching and the sodium are the result of basalt lavas having erupted into seawater. (Sodium, incidentally, is not a vine nutrient; in fact, it can be problematic for vine growth.) In places, the submarine lava erupted into the soft sediments on the seafloor, and the two materials became intimately mixed, producing what is called a hyaloclastite. Promoters of local wines have grabbed at these geological terms.

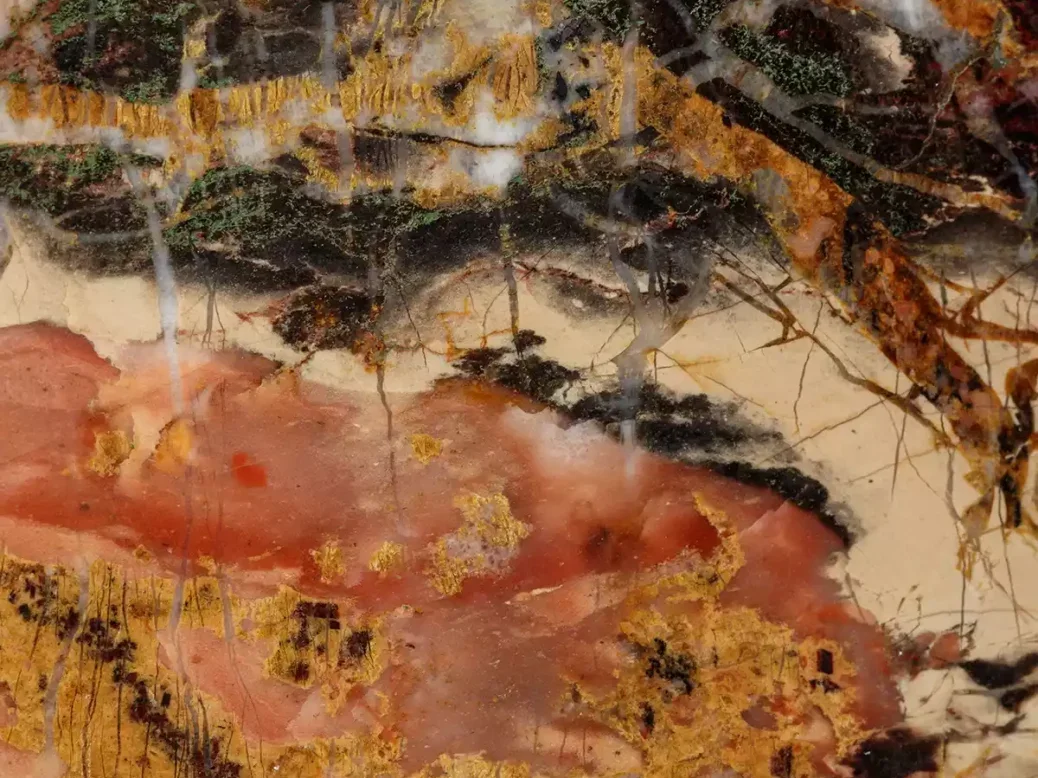

Snow-white pebbles are of quartz, the common form of silica (silicon dioxide). But silica can also form with extremely fine crystals discernible only under a microscope—tiny amounts of impurities that can have a huge effect on the color. Iron can give a red color—the material called jasper, found as fragments at Domaine du Closel but more common at Les Baunâts, across the river. Carbon gives a deep blue-black color. This is called black chert in English, but many English wine writers and promoters use instead a French word—phtanite. Perhaps, as with the flint at Sancerre being referred to as silex, using the French name adds a touch of exoticism and a little mystique?

There are also pieces of Angers slate and schist, a similar material that splits less cleanly because it has undergone additional internal changes, having been more deeply buried. And as it happens, in this region there is an additional difference between the slate and the schist—geological age. The Anjou slate formed around 450 million years ago, in a period of time known as the Ordovician, but the schist is well over 100 million years older than that. It was produced during a time called the Brioverian, as a result of particular Earth movements known here as the Cadomian orogeny. This is all fairly technical stuff, and I mention these names only because I’ve seen all of them on bottle labels and in wine names, and used enthusiastically (though not always correctly) in promotional materials and vineyard commentaries.

The wines from Savennières are largely made from a single grape—Chenin Blanc—but in a range of styles. That’s possible because, apart from differing methodologies, the terrain is so varied: There are hilltops and valleys, and slopes of differing exposure, gradient, and proximity to the river, all of which leads to an array of mesoclimates. And they’re all very different from the wines from over the river—the luscious, sweet wines of the Coteaux du Layon, for instance—even though the soils there are generally similar.

Scientifically, the main contribution of the soils is providing a cohesive strength to curb slippage down the steeper slopes and a suitable drainage in this distinctly Atlantic-influenced climate. There are, however, plenty of claims that the types of soil have a special influence on the wines. I read that, for example, “the schist soils bring a seriousness to the wine,” “quartz and rhyolite play a role in the presence of acidity,” and “sandstone is a factor of powerfulness.” As for phtanite, well, it gives “amazing passerillage” and “conveys to the wines their mystical complex aromas.” No indication is given of how the soils do these things.

The mysterious rocks of Muscadet

Salty breezes from the Atlantic become increasingly noticeable as the river sweeps ever westward, past Ancenis toward Nantes. This is the Muscadet AOC, of most interest to the south of the Loire and most esteemed in the vicinity of the Sèvre and Maine rivers—yet two more southern tributaries. The bedrock throughout the area is still the crystalline rocks of the Armorican Massif, and they continue to present a treasure house of esoteric rock names. Moreover, the kinds of rock can change over very short distances.

On January 25, 1799, the region was shaken by an earthquake. That’s not particularly unusual here—there was a 4.5-magnitude one as recently as 2020—but this one was exceptionally strong, causing widespread damage, including to buildings along the Loire. It was the biggest ever known earthquake hereabouts, and it remains one of the six most powerful in all of France. Important here is the presence of major geological faults, the source of these tremors. As with all faults, the rocks either side have moved, bringing very different rocks right next to each other.

There’s an example just half a mile or so (1km) north of Clisson, where the Sèvre is joined by the little Ruisseau du Chaintreau. One of these major faults passes exactly through here, and it has brought the granite that defines the Clisson cru communal directly next to a rock called gabbro, which then extends northward through the Gorges and Le Pallet crus. Gabbro, the hallmark of the Gorges cru communal, is a dense interlocking of coarse crystals, resulting from the slow cooling and solidification of molten rock down below the Earth’s surface—akin to granite, except that its dark constituent minerals make it almost black.

Serious Muscadet producers have long fought the cheap and cheerful image of their wines. (I read that, staggeringly, the average price paid for a bottle of Muscadet in France is less than €4.) One success has been the better quality resulting from leaving the fermenting must on its lees (fermentation residues) for longer than is usual elsewhere. Consequently, the applications for the higher status of cru communal were based on extending lees aging further, together with restricting yields and specifying the vineyard bedrocks.

There’s a great deal of published scientific research on the effects and merits (and demerits) of lees aging and of yields, but little for the role that bedrock might have. Yet plenty of passionate producers believe that it’s the geology of their vineyards that gives distinctiveness to their wines.

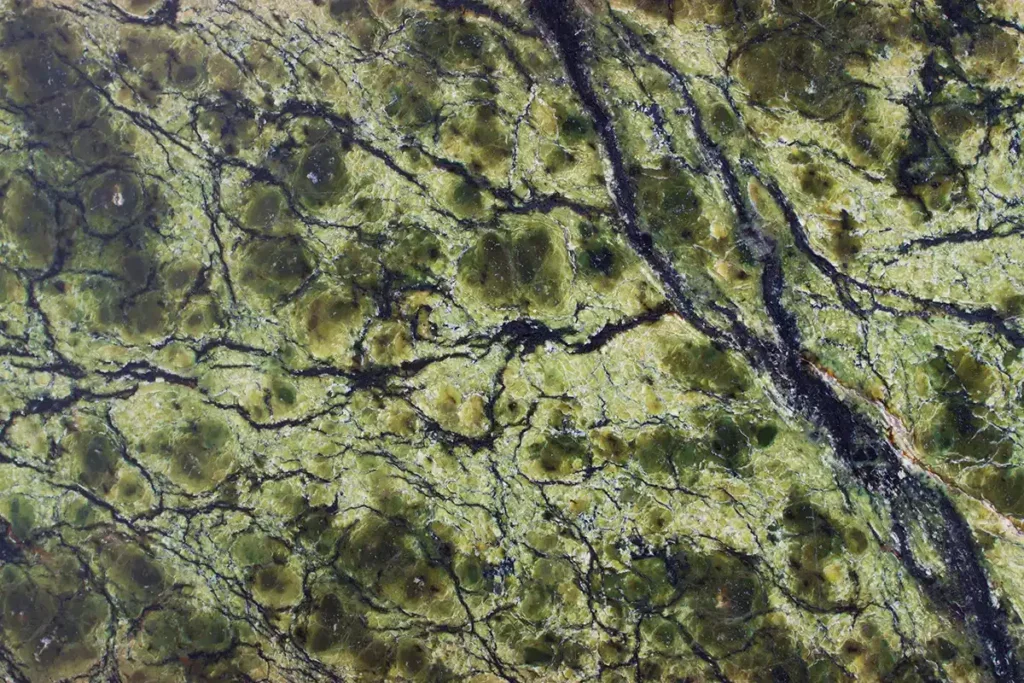

Most of the crus communaux have several different kinds of bedrock; here’s where yet more arcane names come in. We’ve already met schist and migmatite. I believe that the name gneiss is reasonably well known, as is its geological origin—marked change through increased temperatures and pressures when it was buried way below the Earth’s surface. But the defining characteristic of gneiss is its alternating light- and dark-colored bands, and understanding just why that banding developed is a highly technical matter. (Stress-modulated diffusive mass transfer, anyone?) More pertinent is the question of why this is relevant to grapevines, as wine names that include the term imply. Most gneiss is pretty much the same as granite, apart from the banding.

Some producers are very ready to label their wines as “orthogneiss.” I suspect many a geologist would struggle with that one. It means a gneiss that was originally a molten rock, though in view of the extreme changes involved in producing a gneiss, it needs pretty clever geological sleuthing to determine the identity of the original rock. And again, what that distant origin means for vines is unclear. (To reiterate: I am not disputing that the wines from different sites are dissimilar, but questioning whether it’s the subtle changes in geology that are responsible.)

A particularly interesting, almost charismatic, rock—serpentinite (okay, I’ll come clean: It was the subject of my doctoral dissertation)—is found in the Goulaine cru. Much of the land here is marsh, but along Route D105, southwest of Le Loroux-Bottereau, at the bridge over the Goulaine River, is a small but prominent vine-covered hill, Butte de la Roche. It consists of various rocks with names like leptynite, amphibolite, and pegmatite—rather esoteric, perhaps, but all mentioned in wine writings. And along the crest of the hill is the beguiling serpentinite. This waxy, snakeskin-like rock is rich in magnesium, and it is unusual because it can actually be inimical to vines and some other plants; botanists talk of “serpentinite barrens.” However, the vines here manage, perhaps because they are grafted onto Couderc 3309 rootstock, which copes well with all the magnesium. Growers claim that the viticultural challenges are worth it because the stressed vines produce concentrated fruit with distinctive character.

Grapevines grow yet farther seaward, even west of Bourgneuf-en-Retz, southwest of Pornic, a stone’s throw from the ocean. So, the Muscadet produced from these vines is truly a maritime wine. Route D213, the “Route Bleue,” heads north from here along the coast to the grand bridge that crosses the Loire to Saint-Nazaire. The bridge was the longest in France at the time of its construction in 1975, and here the flow of the river as it approaches the ocean can be truly staggering, by far the strongest in all of France (discounting the Rhine). And of all that swirling Loire water, some, just some, will once upon a time have fallen as rain in the Cévennes, on the slopes of Mont Gerbier de Jonc.