Natasha Hughes MW on the influential group of plucky Beaujolais vignerons who held out against industrialization and came to shape the style and winemaking philosophy of the region’s best modern wines.

Kids in France grow up reading about the adventures of Asterix the Gaul.

A series of comic books set in France during the Roman era, each witty, action-packed tale starts with the introduction “The year is 50BC. Gaul is entirely occupied by the Romans. Well, not entirely… One small village of indomitable Gauls still holds out against the invaders.”

When I think about Asterix and his fellow villagers prevailing against the might of the Roman empire, it brings to mind the real-life stories told about Beaujolais’s Gang of Four. It’s said that this resolute group of winemakers held out against the almost overwhelming tide of Beaujolais Nouveau that dominated production in the region from the 1970s through to the early 2000s, and, arguably, set an agenda for change that has now come to dominate the prevailing philosophy in the region.

At a time when most growers used lavish quantities of pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides in their vineyards, the “Gang” believed that more environmentally sustainable practices were the way forward. They questioned the need for manipulative winemaking techniques that altered the intrinsic character of the finished wine, believing that good-quality grapes should be allowed to speak for themselves. And they fought hard against the idea that the Beaujolais should be made in high volumes, marketed as a commodity, and sold at low prices.

Like all good stories, though, there’s more than an element of myth-making to this account of what was widely seen as the start of Beaujolais’s natural wine movement. To begin with, the term ‘Gang of Four’ was invented wholesale by US importer Kermit Lynch as a way of marketing the wines of Marcel Lapierre, Jean Foillard, Jean-Paul Thévenet and Guy Breton. Not only did the four growers not think of themselves in these terms, many other producers, all motivated by a similar philosophy, worked alongside them, among them key figures such as Joseph Chamonard, Yvon Métras and Georges Descombes.

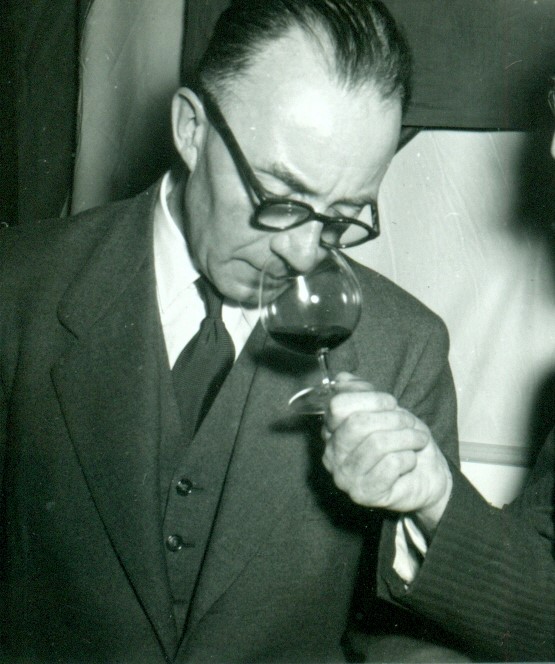

Nor did the “Gang” invent their approach to viticulture and vinification from scratch. Their inspiration came from an unexpected source. Jules Chauvet was a négociant based in the northern fringes of Beaujolais who dreamed fondly of the Beaujolais he remembered from his youth—juicy, fruity wines with vibrant acidity and modest levels of alcohol. Chauvet considered the simple, bubblegum-scented Beaujolais Nouveau wines, and the quasi-industrial processes that produced them, to be both an aberration and an abomination.

Chauvet was not just a négociant, though, he was also a winemaker and a chemist, and had spent much time trialling approaches that would allow for the creation of the kinds of wines he was interested in. Among other avenues of experimentation, Chauvet was interested in the possibilities of carbonic maceration, a technique Louis Pasteur had first explored in the 1870s, but he also investigated the microbiology of fermentation, advocated for the use of spontaneous fermentation, and, perhaps most famously, was a keen critic of the over-use of sulfur dioxide in winemaking.

Chauvet’s contribution to the debate about the role of sulfur is widely misunderstood. Although he is widely regarded as the father (or at least the godfather) of the anti-sulfur movement, Chauvet had nothing against the use of sulfur as a preservative in winemaking per se—what he railed against was the over-use of sulfur, particularly when it was deployed at harvest (when it could inhibit the ability of indigenous yeasts to dominate the final, aerobic part of the fermentation). He was a firm believer, instead, in the use of scrupulous hygiene in the winery so as to prevent spoilage organisms from taking hold of the vinification process.

Nevertheless, it was Chauvet’s scepticism about the over-use of sulfur that first draws the attention of Beaujolais’s most rebellious winemakers to him in the late 1970s, and the results of his research into all aspects of winemaking become the bedrock of a new paradigm in the region. It’s easy to see, in retrospect, why the message Chauvet preached was so attractive to producers in search of an escape route from the grinding labor and poor economic returns that came from catering to the Nouveau market.

If you fast forward several decades, it’s clear that Chauvet and his acolytes continue to influence the direction of viticultural travel in Beaujolais. The first evidence of this comes directly from the vineyards, where even in winter the dominant color in many plots is green, testament to the fact that fewer and fewer growers now use herbicides to keep competing grasses under control. Many growers now adhere to sustainable viticultural practices, and more than 150 estates in the region either have organic certification or are in the process of conversion to organics. Still more farm, more or less organically, without seeking certification. Biodynamic certification is a relative rarity in the region, but many of the more forward-thinking producers use elements from the biodynamic playbook to enhance their work in the vineyard. And many younger growers are finding that regenerative farming practices are providing a strong sense of direction.

The winemaking practices espoused by the Gang’s members—and their fellow travelers—have become routine for many of the region’s best producers, regardless of whether they consider themselves to be “natural” winemakers or not. The use of sulfur is generally minimal, typically relegated to almost homeopathic doses at the time of bottling. True, some estates make a “no-sulfur” cuvée, but this is typically part of a broader range rather than being considered to be the gold standard.

The use of indigenous yeasts in extra-cellular fermentation, too, is now widely practiced by wineries working on an artisanal scale, and even some of the larger domains. And although some wineries produce cuvées in which the influence of new oak is marked, most Beaujolais still puts the emphasis on fruit character, with maturation taking place in stainless steel or cement tanks, older oak (often large-format barrels) or, increasingly, amphorae, and concrete eggs.

But, arguably, Chauvet’s most profound influence on Beaujolais has been the widespread adoption of carbonic maceration—or, at least, semi-carbonic maceration—as the winemaking norm in the region. Although other methods of vinification are used—most notably “Burgundian” techniques in which grapes are largely de-stemmed and the fermentation is extra-cellular—some form of carbonic or semi-carbonic maceration is more typical. So much so that, in the minds of most wine lovers, winemaking technique and region are inextricably linked.

If the history of Beaujolais were to be presented in comic strip form, you might end up concluding that Chauvet and his winemaking gang not only held out against superior commercial forces against all the odds, but that their view of what the wines of Beaujolais could—and should—be has influenced us all.

This article is produced as part of a partnership between Wine Scholar Guild and The World of Fine Wine. Both Wine Scholar Guild and The World of Fine Wine strive to provide the highest calibre of editorial and wine education content. We are proud to share the perspectives and knowledge cultivated through this collaboration, fostering a lifelong appreciation of distinguished wine, winemakers, and their culture.