Raymond Blake reviews Oz Clarke’s Story of Wine: 8000 Years, 100 Bottles by Oz Clarke.

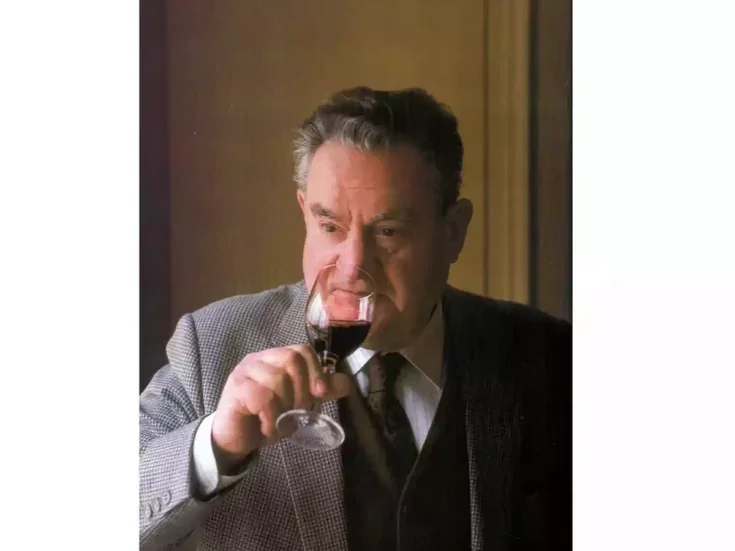

Not many wine people are widely known and easily recognized by their first name only, though not many have a name as memorable, easy to say and pronounce, as “Oz.” It wasn’t always thus, for Oz Clarke was christened Owen and only became Oz when teammates on his school cricket eleven nicknamed him Oz because they reckoned he played the game like an Australian. That said, one cannot help feeling that even if Oz Clarke answered to a more prosaic John or Peter or Tom, wine people would instantly know who was being spoken of. He’s that sort of guy; he’s more than just a memorable name.

Nobody paints a verbal picture of a wine’s flavor quite like Oz does. And in this he is well served by his thespian background (he narrowly escaped a career as an actor before settling on wine). The theater’s loss was wine’s gain—something I have learned to my great delight on every occasion we have met but most especially in 2019, when I commissioned Clarke to speak at a grand wine dinner attended by 180 aviation executives from around the globe (see WFW 68, pp.142–47).

His contribution was the highlight of the evening, finishing with a resounding flourish when describing the final wine of the dinner, a Château d’Yquem 2009: “Astonishing wine. Its sheer richness, its exotic fruit cocooned in honey and cream, is so viscous and lush, your mouth will feel coated with succulence for an eternity after you swallow. And if you wait a moment or two more, you’ll realize that the flavors are still spreading out across your tongue, pineapple and peach are turning to barley sugar, heather honey is turning to orange chocolate, fresh cream thickens into butterscotch and caramel fudge, and every sensation is wrapped in liquid gold. That’s Yquem for you.”

Corralled between the covers of the Story of Wine: 8000 Years, 100 Bottles, Oz Clarke’s prose flies at a lower altitude than that passage. His achievement here is to take a huge sweep of vinous history and skip across it at speed, alighting on dozens of salient points along the way. Each stop comprises a short essay, usually with a vintage date as its starting point. At times you have little idea what direction Clarke will head off in, but you do know you are guaranteed an interesting story. And while the prose may be less baroque than the paean to Yquem, Clarke does allow himself some memorable sparkles and flourishes.

Considering the ill effects of heavy chaptalization, “[…] when a Bordeaux from a frankly execrable vintage would appear to be quite rich and almost sweet until the tug-of-war acidity threatened to part your gums from their teeth.” Or when telling the tale of the Douro Valley’s first serious table wine, Barca Velha, and giving some background color: “It always amazed me how poor Douro red wine was. It was offered to you almost apologetically if you dined with the Port shippers in Oporto. After they’d enthusiastically plied you with slugs of icy white Port, a barely digestible drink of which they seemed inordinately proud, they would then ladle out a dark, chewy, baked red wine simply because the main course required it […]. Indeed, the leading Port houses used to make the most cloddish table wine.” Or his first experience of boxed wine: “It must have been pretty bad, because I can still remember the taste of it. My first bag-in-a-box wine. It came from Bulgaria. And it tasted of geraniums […]. I later discovered this rather nauseating geranium taste came from lactic acid bacteria reacting with sorbic acid—a chemical used to combat the growth of fungus in the wine.”

The accessible wisdom of Oz Clarke

More seriously, Clarke’s ability to skewer pomposity and plutocratic connoisseurship is formidable: “I didn’t go to Robert Parker’s Gala Hedonist’s Dinner in 2015. I wasn’t invited. And the idea of paying £1,800 for a good dinner and taste of eight top wines didn’t give me any warm feelings. Indeed, the whole event rather disturbed me. This was part of a ‘Grand World Tour’ being undertaken by Parker, a kind of imperial long last farewell tour, a grand parade of the world’s most expensive wines being drunk in the company of the world’s richest wine lovers. But this wasn’t how Parker started out. And this wasn’t what Parker’s stated purpose was in the world of wine.”

Taking the narrative back to the late 1970s, when Parker started to write about wine, Clarke reminds his readers that the man who went on to be dubbed the emperor of wine by Elin McCoy originally set out to democratize wine, to give objective assessments of wines, “in a world where most wine criticism was far too cozy with the hand that fed it—the wine trade.” Parker’s name was made by his championing of the 1982 vintage in Bordeaux, and he went on to wield extraordinary influence for three decades thereafter, literally changing wine styles as winemakers sought to craft wines that found favor with his taste buds. But of his original intention, Clarke has this to say: “Less encouragingly, his attempt to democratize has actually created an elite; his marking system offers certainty where no certainty exists, substituting blithe reassurance for hard-earned personal opinion.”

Clear-eyed conclusions and assessments such as this form the backbone of this book, and it contains so much accessible wisdom it could act as a wine primer for neophyte and veteran alike. Thanks to its format, it is also perfectly suited to our sound-bite, bullet-point age, with attention spans corroded by exposure to torrents of information and non-information, truths and falsehoods, facts and non-facts. Open it at any page, and you will be treated to an engaging tale that always has a pin-sharp opinion at its core. And the narrative is always driven forward by enthusiasm—an enthusiasm for wine in all its iterations that is boundless and of which I have been an entertained “victim.”

I’ll not easily forget Oz’s enthusiastic insistence, at a wine tasting in Austria years ago, that I try the local Uhudler wine. His eulogizing of it swept my skepticism aside and led me to sample it. While he delighted in its wacky, miles-wide-of-center style, I searched out a sharp Sauvignon Blanc to use as mouthwash. That same enthusiasm runs rampant across these pages, sustaining the reader’s interest at every turn.

First published nearly ten years ago as The History of Wine in 100 Bottles: From Bacchus to Bordeaux and Beyond (2015), this revamped, renamed, and substantially redesigned second edition comes in a chunkier format. I especially like the tactile cover, with the title deeply embossed in white lettering on dark green (British racing green?). In terms of design and layout, it is a signal improvement on the original 2015 edition, though the use of a glossier paper in the former facilitated better reproduction of the numerous images. None of these changes, however, can obscure the wealth of knowledge contained therein.

Oz Clarke’s Story of Wine: 8000 Years, 100 Bottles

by Oz Clarke

Published by Pavilion (imprint of Harper Collins Publishers); 320 pages; £30