Examples of early cinema, such as the Lumière brothers’ Partie de Cartes, remind us of the central significance of wine in French culture, says Stuart Walton.

A trio of genial old buffers sits at a cafe table. Two of them who are positioned in profile to us are playing cards—écarté, to be precise. While the one on the right deals the next hand, the third, centrally seated figure facing us calls to a waiter, who promptly appears from the right of the shot bearing a tray with a bottle and three glasses. Our host pulls the loose cork from the bottle and pours out three good measures of what looks like red wine, but which interestingly foams up a little into a top-layer of suds. He hands the drinks round, and they all imbibe cheerily. Nobody pays any further attention to the extravagantly moustached waiter, a figure from light opera whose tireless comic mugging threatens to steal the show.

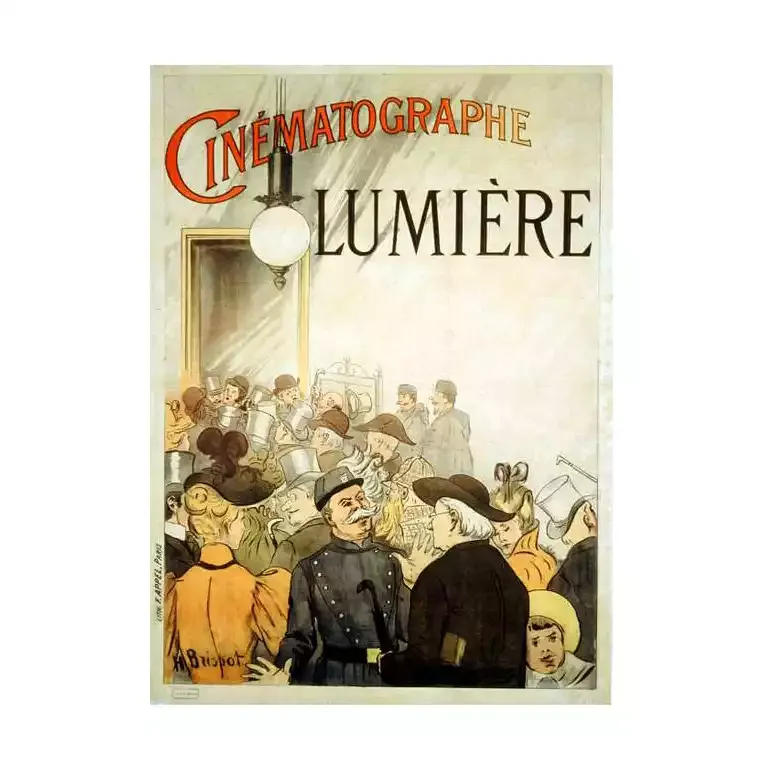

Partie de Cartes (1895) is one of the earliest short films of the Lumière brothers, Louis and Auguste. It was shot on their patented Cinématographe, a combined film camera and projector, and probably first shown to paying audiences in early 1896. It is 49 seconds long. The only actor credited is Antoine Féraud, who plays the waiter, and whose career in cinema was over within a year of its invention, but the man on the left is the Lumières’ father, Antoine, born in 1840.

In another of the brothers’ short films of the same period, Le Repas de Bébé (36 seconds), set outdoors on a breezy terrace, Auguste Lumière spoon-feeds his infant daughter Andrée rather messily with her breakfast slop, while his wife Marguerite, got up in a staggering matutinal outfit of carnival stripes, with voluminous puff sleeves and lace trim, pours and stirs her coffee with impressive gusto. To the right, a couple of what look like Cognac bottles stand ready, in case either Maman or Papa fancy a sharpener to start the day.

We are reminded in these simple scenes of the central significance of wine in the French cultural milieu. Three dignified gents taking their leisure at cards may be an unremarkable enough scene of congenial sociability, but the arrival of the aproned waiter and his tray turn the moment into something altogether more festive. The wine is poured efficiently quickly, without the least hint of ceremony, the first measure judiciously topped up a little before the glasses are handed round, and the nunc est bibendum nature of the moment is what licenses the comic antics of the waiter. His theatrical gestures – hands to the sides of his face in mock astonishment – and almost sardonic applause, presumably intended in response to the game, make him a stock comical figure, a belated Pulcinella escaped from the commedia dell’arte, but also a recognisable progenitor of the stars of silent comedy to come.

Partie de Cartes redux

Partie de Cartes was the first film in cinema history to be remade. In 1896, another of the French cinema pioneers, Georges Méliès, shot the scene again, at a more ambitious 67 seconds, with an identical mise-en-scène of three men at an outdoor table playing cards. This time, though, the waiter is a hearty, broad-shouldered woman, summoned initially to the table by a young girl. She brings wine, which is poured into what came to be known as highball glasses. The men drink appreciatively. Within moments, the man who has poured the wine (played by Méliès himself) reads something hilarious from his newspaper, which sets off the man to the right (played by Méliès’ brother Gaston) in a table-thumping guffaw. Once again, the appearance of the wine turns a bland afternoon into a properly recreative moment, conferring vivacious cordiality on the scene.

So central is the representation of wine to the creation story of moving pictures that Partie de Cartes was remade yet again in 1897 by an Italian director, Leopoldo Fregoli. Shot in France like its predecessors, and running to 51 seconds, Fregoli’s scene retains the trio of card-players, but adds a very jolly lady in a straw boater, who doesn’t join the men’s game, but does share their drinking. There are six actors. A flat-capped steward oversees the arrival of a serving woman—his wife, presumably—who brings a tray bearing a very ornate crystal decanter. The seated woman pours the wine into elegant little glasses. This time, the scene is brimful of busy movement, and the film was partly colorized, to give the central man a light green waistcoat, the man on the right a cap in the same shade, while the woman’s sleeves and hat decoration are rendered in summery rose-pink.

The Lumières are credited with inventing the garden hose gag (in L’Arroseur Arrosée, 1895), but their immediate legacy, in a medium they famously thought had no future as a commercial enterprise, was to put before cinema audiences images of their own everyday pleasures, the human form at play, released from duty, sitting in the sun, enjoying the intoxicating drink that was their birthright.