The second-smallest South American country, Uruguay is dwarfed by its neighbors. But a progressive, risk-taking culture has produced a proudly different wine scene that is ripe for discovery, says Amanda Barnes.

Uruguay has always had an intriguing combination of being at the heart of South America but still with an umbilical cord to Europe. The second-smallest nation on the continent, it sits between titans Argentina and Brazil. Although relatively quiet and unassuming, Uruguay isn’t afraid to ruffle a few feathers either, proudly claiming its title as the world’s first football champion at the World Cup, the birthplace of tango, and home to the world’s longest carnival. Uruguayans certainly do know how to have fun and exude that Latin joie de vivre.

But Uruguay is also a deeply introspective country, with one of the most progressive democracies not just in South America but in the world. It was the first country to legalize marijuana (in 2013), was the first nation to provide every child with a laptop (since 2009), and has a turn-out rate of more than 90 percent at national elections. For a relatively young democracy, independent since 1828, it puts many of the dinosaur democracies to shame. And it is this interesting parallel of sensibility and risk-taking that makes Uruguay such an interesting wine country, too.

Vinous foundations transplanted from Europe

Uruguay’s wine story really develops in tandem with its foundation as an independent country. There’s little doubt that vines were planted here before that—there are records of Jesuits making wine in eastern Uruguay in the 1720s—but Uruguay’s wine industry only really started to find its feet with the influx of European immigrants towards the end of the 19th century.

“The Spanish and Italian immigrants, who have been arriving in Uruguay since the 1850s, all brought their own grapevines with them,” explains Pablo Fallabrino, a third-generation vigneron in Canelones who continues to make many Piemontese varieties originally brought by his grandfather in 1920. “It was mainly northern Italian varieties that dominated early on… with Fresa, Barbera, Nebbiolo, many Moscatos, Grignolino… But there were also lots of Spanish and French varieties—Gamay, Cabernet, and, of course Tannat.”

The enormous influx of immigrants during the period (by 1889 some 70 percent of the adult population were immigrants) made this new nation a viticultural petri dish. There was land aplenty to plant, eager hands to do it, and ore than 80 grape varieties passing through the docks of Montevideo. And with this panoply of weird and wonderful grape varieties and a legion of eager settlers, the wine industry steadily took root around the country.

The river of painted birds

With its neat pear shape spanning 340 miles x 310 miles (550 x 500km), Uruguay has a maritime climate throughout the country and its wine regions. Contrary to the largely arid climates of Argentina’s and Chile’s wine regions, Uruguay has a humid coastal climate where more than 39 inches (1,000mm) of rain a year is the norm. Altitude doesn’t play any part in Uruguayan viticulture either, with most vineyards being less than 500ft (150m) above sea level, and the highest hill in Uruguay, Cerro Catedral, only scraping 1,683ft (513m) and casting no such rain shadow as found near the Andes. Even the coastal regions of Chile, with their cool Pacific influence, are vastly different from the mild Atlantic climate of Uruguay. Uruguay’s is indeed nothing like the climates of neighboring Argentina or Chile farther afield, and it is cooler than most of Brazil’s wine regions. Parallels are much better drawn with Bordeaux or even Galicia, which is why Uruguay has earned the moniker of being a “piece of the Old World in the New World.”

Water also plays a big role in Uruguay, and not just as rainfall. Most of Uruguay’s borders are in fact water. The River Plate skirts down its western frontier, wedging Uruguay away from Argentina, and it spills out into one of the largest river basins in the world. The mouth of the river appears as a sea between the capital cities of Montevideo and Buenos Aires. It isn’t until beyond Montevideo that the River Plate gradually becomes the Atlantic Ocean, which lines Uruguay’s southern frontier until it reaches the land border with Brazil This aqueous landscape not only tempers the diurnal range giving Uruguay a rather mild climate, it is also what makes Uruguay such an inviting haven for birds.

Uruguay means “river of the painted birds” in the native Guarani language and, with 484 species of bird inhabiting its folds, Uruguay is a bonafide twitcher’s paradise. But the vivid birdlife makes the hundreds of grape-growing families twitch somewhat uncomfortably during the growing season. Being on full alert and with scarecrows on bird watch is rarely enough, and most of the vineyards are equipped with a combination of bird nets, lasers, and sound boxes, as well as often all too futile attempts to retain families of larger predatory birds.

Soils of mother rock

While its climate and birdlife are somewhat consistent across the country, the soils are not. According to Uruguayan soil expert Alfredo Silva, Uruguay has 99 different soil types, some of which are from some of the most ancient soils on the planet, originating from the supercontinent of Pangea. “We have very old soils in Uruguay, from the mother rock shared with South Africa,” he explains. “Our geology is much more varied than in neighboring countries. Uruguay calls your attention because even though it is very small, the geological variation is very large.”

This all gives winemakers quite a playground in which to work, and it’s what’s underground that really marks the difference between wines from different vineyards in similar regions. The majority of wine producers in Uruguay are family wineries with small vineyard estates, usually in one location. And so their own soil profile and unique vineyard site helps carve out their individual identity.

A handful of larger wineries, however, have been on an exploration of Uruguay’s terroirs. “Since the early 2000s my family have been looking to make wines in different regions in Uruguay, and when a study came out about soils for forest plantations [at a similar time] we took advantage of the studies to plant new vineyards in areas that seemed interesting, and we’ve been on a journey of discovery since then,” explains Santiago Deicas of Familia Deicas, who are now working with 15 different vineyards and soil profiles around Uruguay—the country’s most expansive single vineyard portfolio. “Uruguay has this incredible diversity of soils,” he adds, explaining that Uruguay has a similar range and quantity of soil types as the US, despite being less than 2 percent of its size. “Within really small distances we have really different soils—for example, in one of our vineyards in Garzón we have a very rocky weathered granite, and just a few kilometres away we have calcarious limestone!”

Familia Deicas’s agronomist Gustavo Blumetto continues the thread: “Uruguay is a small country without much climate variability between the wine regions, but it has an enormous diversity of soils. It’s this that gives each vineyard and wine its own character.” Soils, of course, are only important for wine when people cultivate vines in them. And the diversity of Uruguay’s wines is down to the choices made overground by winemakers and wine families who have gradually woven together Uruguay’s tapestried wine map.

Survival of the fittest

The viticultural pioneers of Uruguay made their choice of what to grow before even setting foot in the Americas. Their decisions were often stowed away in their luggage that made it across the long sea voyage from Europe to Uruguay more than 100 years ago. “We undoubtedly have so many varieties because of all of the different immigrants,” says fifth-generation vigneron Gabriel Pisano. “And there was never any regulation, and still isn’t, on what you could plant here. And so, everyone planted what they wanted.”

But even though each family had, and continues to have, its own favorites, it soon became clear that they all wanted Tannat, too. Ever since first being planted in the mid-1800s, it has not stepped off its pedestal as Uruguay’s champion grape variety. By the late 1880s, Uruguayan Tannat was winning awards in the international wine shows of Paris and Barcelona, with the wines of Pascual Harraigue in Salto, and it continues to take home clutches of awards in international competitions today and to dominate the wine scene (see also Julia Harding MW, “Tannat: Home Away from Home,” WFW 61, 2018, pp.172–78).

Tannat, or Harriague as it is still sometimes called locally, accounts for some 27 percent of Uruguay’s vineyard plantings. “We didn’t choose Tannat, Tannat choose us!” Reinaldo de Lucca, a renowned grower in Canelones, explains emphatically in his vineyard, where he also grows Nero d’Avola as a nod to his heritage. “It’s only because Tannat performs so well here that growers kept growing it, or asked their neighbors to give them some of these successful Tannat vines, too!”

Originally from southwest France, Tannat certainly did suit the Uruguayan climate. Its thick skins were impervious to the mildew and rot that so readily affected more delicate varieties, and—when often compared to the lighter Italian varieties that were à la mode in Uruguay in the 19th century—its deep color, high acidity, feisty tannins, and rich aroma each vintage was enough to convince growers to plant more.

Even with Uruguay’s heyday of hybrids, which began arriving in the mid-1900s and pushed vineyard plantings to an all-time high of more than 47,000 acres (19,000ha) in 1950, Tannat never lost its currency in Uruguay. When flying winemakers first started coming at the turn of this century, they also backed Tannat as the variety to help propel Uruguay to the world stage as Malbec had done for Argentina and Cabernet Sauvignon had done for Chile. Tannat wasn’t only consistent in Uruguay’s variable vintages, it actually performs better in a more humid climate. “Tannat needs some humidity to balance its tannin, sugar, and acidity,” explains Santiago Deicas. “Otherwise, the sugars accumulate before the skin ripens.”

That’s not to say that all Uruguay’s Tannats are made equal. Although in general you could certainly say that Uruguay’s Tannats are much better balanced and more supple than those of Madiran, and more savory than those of Northern Argentina, there are myriad expressions of Tannat in Uruguay. Tannat, as well as Uruguay’s other varieties, can take you on quite a tour of the wine regions and the different approaches of Uruguay’s wine families.

Tasting through Uruguay’s wine regions

Canelones

The heart of Uruguay’s wine production, with more than two thirds of the country’s vineyards, is Canelones. As a large province that engulfs Montevideo, it’s no coincidence that the main wine region developed right on the doorstep of the most populous city of Uruguay. In fact, one in three Uruguayans live in the capital city of Montevideo, which gave Canelones unparalleled access to market.

Although the development of Canelones as a wine region was largely due to its convenient location, the fertile soils and undulating hillsides were also ideal for viticulture. Vineyards and family wineries thrived here with some 900 growers still based in Canelones and Montevideo today. “My great-grandfather came from Liguria to Uruguay in around 1870 to ‘make America,’ as everyone leaving Italy was doing, and make some money to take back to Italy,” explains fourth-generation vigneron Daniel Pisano, who today runs Pisano Family Vineyards with his brothers. “Although my great-grandfather never settled here, my grandfather—one of his nine children—did. He was a peasant working on other Italians’ estates here in Canelones at first, Italian immigrants who had arrived before him, but after saving some money he was able to buy his own plot and he started planting our family vineyard in 1916. We still have some of the vintages my grandfather made.”

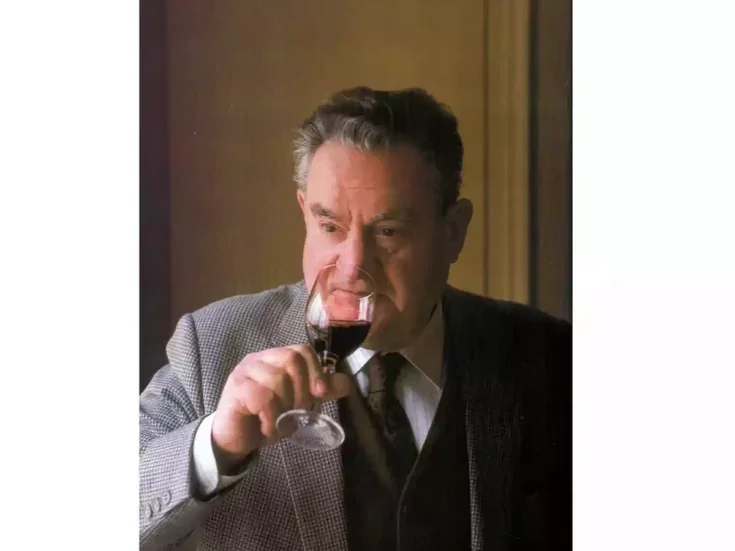

It’s families like the Pisano clan that really capture the essence of Canelones as a wine region; multi-generational families who have cultivated their family plots for more than a century and passed down their knowledge in the cellar and vineyard. On a visit to Pisano, you will often sit to taste with one, if not all three, of the brothers running the show today—Gustavo the winemaker, Eduardo the agronomist, or Daniel the export manager—all heavily moustached, with unruly eyebrows and contagious senses of humor. Within a moment of being there you’ve fallen for the charm of the Pisano family and are welcomed like an old friend.

The tasting room itself is part of the old family house and is crammed with old photos, family souvenirs, and library vintages that have been collected over the many years. Tradition runs deep here, but there’s also innovation bubbling over. Gustavo has a deft hand in the cellar and the family produced the world’s first sparkling red Tannat—a lively and peppery traditional method sparkler. There’s always something new to taste here, either with Gustavo or with Eduardo’s son, Gabriel, who also has his own line of wines, Viña Progreso. Although there’s always something new coming into the Pisano portfolio, the family is loyal to its own style and tastes. “Our wines are: Pisano first, then Uruguayan, then South American, then New World!”, explains Daniel passionately. “That’s why Uruguayan wine is such an experience. Every wine from every family in Uruguay is different and very personal.”

This family flair and blend of tradition and innovation runs through many of the family wineries in Canelones. Take Fabiana Bracco in the coastal sub-region of Atlántida, for example. Vivacious and irrepressibly bubbly, Fabiana was lured into the world of marketing until her father became unwell and she stepped in to take over the family vineyard. Like many of this generation of vignerons, she switched the focus of the family winery from table wines, to fine wines but didn’t want to undermine the heritage built by her father.

“Moscatel was one of the first vines planted in Uruguay, and when I got involved in the family winery, I didn’t want to lose the traditions that identified my family for generations,” Fabiana explains. “Many people just told me to rip out our Moscatel vines and plant new varieties, but my heart spoke louder and so we’ve been working hard to show its potential today and made it a fundamental part of our philosophy.” The fragrant, dry white wine in question is now one of her best-selling and has helped revive interest in this lesser known but widely planted wine grape, as well as in Ugni Blanc which she is also championing. Fabiana is also writing her own chapter, by planting Cabernet Franc and Petit Verdot, blending tradition and innovation in the Bracco Bosca portfolio.

Just a few miles down the road, also in Atlántida, is surfer-cum-vigneron Pablo Fallabrino with a similar story. He took on his grandfather’s winery and has made it his mission to reflect the family’s Piedmontese heritage in his wines, which include Nebbiolo, Arneis, and Barbera. But Pablo, too, has his eye on new horizons. And his latest novelty reflects another of his passions—cultivating marijuana. Pablo is the first to make cannabis (CBD) infused wines in South America and has a rather fun duo of “Soul Surfer” wines: an unfiltered white Traminer blend and a red Barbera, which sold out in the UK within weeks of their release.

What weaves together the fascinating narratives of the wine families of Uruguay is this gentle maneuvering and broadening visions of each consecutive generation, which add to their family narrative without putting a pause on tradition. Pizzorno is another key producer in Canelones, the family firm now run by the third and fourth generations. Carlos Pizzorno pioneered Uruguay’s first carbonic maceration Tannat, which is a lively, juicy, and subtly herbaceous wine, and his son Francisco has been driving boutique tourism in the region. He opened a guesthouse on the family vineyard a few years ago, which has inspired a couple of other Canelones wineries to follow suit, as well as a family-style restaurant. Informal winery restaurants are also the norm in Canelones today, with particularly charming ones including Artesana (which also has Uruguay’s only Zinfandel vines), Spinoglio, and H Stagnari.

Without a doubt though, the leading winery for tourism in this region is Bouza. Juan and Eliza Bouza are actually relatively new to the wine industry, having co-founded the project with renowned Uruguayan winemaker Eduardo Boido in 2000. From the very beginning, however, Bouza was focused on making premium wines and spared no expense in their beautiful cellar and modern winery, kitted out for microvinifications of small lots. But the cellar isn’t the only highlight of visiting Bouza; others include the excellent restaurant, where their diverse portfolio of wines is expertly paired with contemporary Uruguayan cuisine, and their garage wine bar serving tapas. Car fiends will likely vote for Juan’s impressive classic car collection as the main attraction.

What’s interesting about Bouza’s story is how, even as new producers, they also looked to their ancestors to pave their own path in wine. Coming from families of Galician descent, and with some extended family still in Rías Baixas, they asked family for some Galician vines and planted Albariño in Canelones and Montevideo in 2001. This rather inspired move saw them not only make the first Albariño wines in South America, but ignite an important Albariño movement in Uruguay, which is undoubtedly the rising star of Uruguay’s white wines. The success of their Albariño has also encouraged them to expand farther afield, planting new vineyards in the rare syenite soils of Pan de Azúcar, and a hilltop vineyard on poor, volcanic soils in Las Espinas in the Maldonado region. Here they are making totally new expressions of the classic Uruguayan varieties, including Tannat and Merlot, as well as making refreshing and vibrant Riesling, Albariño, and Pinot Noir. But for now, the lion’s share of their wines still come from the traditional wine regions of Canelones and Montevideo, where they have three vineyards, including their prized vineyard in Las Violetas.

It’s this sub-region that has become particularly renowned for its age-worthy Tannat. The Carrau and Marichal families also have vineyards here, and many producers purchase grapes from Las Violetas, because the breezier location and limestone-rich soils are known for yielding wines of concentration and structure, with tannins that become more filagree with time. As with most of the Tannat wines of Canelones, the region offers wines of subtle, savory, and dark-fruit aromas.

Tannat from Canelones is very much the benchmark for Uruguay, but winemakers are increasingly looking beyond it to carve out new wine stories and identities in their portfolio. It is this thirst for knowledge that took the Deicas family beyond their flagship vineyard in Juanicó, Canelones. One of the most interesting of the finds in their hunt for distinctive new vineyard sites and unique wine profiles is the development of their Mar de Piedras vineyard in San José.

San José and Colonia

San José is, in fact, a traditional wine region to the west of Canelones, with fertile clay-loam soils and very stable temperatures offered by the three rivers that surround the region. It’s often seen as the little brother of Canelones and is home to three dozen producers. But the Deicas vineyard is a world apart from classic San José. Planted on the slopes of Sierra de Mahoma, the vineyard is scattered with enormous boulders, which make it look like a giant’s boules pitch, and it has a vertical schist soil that drains very well—an asset in rainy Uruguay. “The vines basically don’t have any other soil and so they grow directly into the rocks,” explains winemaker Santiago Deicas, who is tireless in his search for new, extreme vineyard locations. “They are the longest—or deepest—roots I’ve ever seen in a vineyard. These deep root systems give this incredible natural balance to the plant and lend a really distinctive character of iodine and meat to the wines.” It’s that blood and stone character that really marks the Tannat wines and red blends from the region, with Cabernet Franc also performing very nicely here.

As you continue farther to the west, San José extends to Colonia and the beautiful riverside regions that are nestled on the banks of the River Plate. Gravels and limestone dominate here, and the slightly warmer temperatures lend a richer profile to the red wines, with a riper, more voluminous style than in the rest of Uruguay. Vineyards are nothing new in Colonia, and in fact Uruguay’s oldest-running winery, Los Cerros de San Juan, founded in 1854, is based here. But what is rather new is the hive of agritourism. Just a short boat journey from the affluent Tigre suburb of Buenos Aires, Colonia attracts a well-heeled crowd of Argentines throughout the summer, who come to enjoy the altogether different wines of Uruguay, with the altogether similar beef-dominated cuisine. A highlight on the wine route of Colonia is the village of Carmelo where a handful of boutique wineries are open for tastings, as well as the stunning wine lodge, winery, and restaurant of Narbona, which claims Uruguay’s one and only Relais & Chateux hotel status.

Cerro Chapeu

Throughout Uruguay’s inland regions there’s less of a tourism flow, but it is still a land of notable wine production, from the supple wines of Salto, down to the hearty wines of Durazno in the very center of Uruguay. Perhaps most notable of the inland regions for wine quality though is Cerro Chapeu. The region sits right on the border of Brazil. Indeed, its main town has a Brazilian half and a Uruguayan half—cross the road and signs switch from Spanish to Portuguese. The Uruguayan half is called Rivera, the Brazilian half is called Santana do Livramento, but it is only a line on a map that separates them.

Rivera as a wine region was pioneered by the Carrau family in 1975. The Carraus had been making wine in Canelones since 1930, and stemmed from a Spanish family making wine in Catalunya since 1752, and so winemaker Quico Carrau was well-known in Uruguay’s wine world. He was approached by UC Davis to help find the best soils suitable for Vitis vinifera production in Brazil, and the red sandy soils of Rivera came out on top. Brazil’s modern wine industry took root over the border in Brazil’s Campanha region, and Quico Carrau planted 86 acres (35ha) for himself on the Rivera side of Cerro Chapeu.

“Cerro Chapeu has these sandy soils with low fertility, which means the [tannic] seeds in red varieties mature much quicker than in Canelones or Montevideo,” explains Quico’s son, Dr Francisco Carrau, who inherited his father’s studious genes and is a respected winemaker and researcher in enology. “This means that the tannins are much softer and rounder, and I believe Rivera can make great Tannat, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Nebbiolo for that reason.”

Cerro Chapeu’s Tannats are certainly renowned for their silkier texture compared to wines from other regions of Uruguay, and they have an appreciative market in Brazil especially, with many wine tourists hopping across the border to visit the modern gravity-flow winery.

Maldonado

Brazilian tourism has also driven a boom in Uruguay’s fastest emerging wine region, Maldonado. On the eastern side of Uruguay’s coast, Maldonado connects with Rocha and then Brazil’s southern tip. The golden sandy beaches of both states, as well as the cosmopolitan capital of Punta del Este in Maldonado, are a big draw for international tourism, and the region’s population swells by ten fold each summer. This was one of the reasons why the modern pioneers of Maldonado, Álvaro Lorezno and Paula Pivel, built their Alto de la Ballena winery here—in the knowledge that they would be on the doorstep of Punta del Este’s thriving tourism industry. They also conducted some soil studies and found that, quite unlike the richer soils of Canelones, Maldonado had typically well-draining granite soils, which seemed like a smart proposition for mitigating the challenges posed by summer rains.

“At the time, everyone thought we were pretty loco to be planting in a new region with these tough granite soils, which were always seen as bad farmland,” says Álvaro, who, with Paula, quit their jobs in Montevideo in 2000 and bought 50 acres (20ha) on a hill known for whale spotting, just a few miles from the sea. “But after a couple of years, winemakers starting coming to visit and taste the wines. And now we’ve seen an explosion of vineyards on ‘bad farmland.’”

Their hunch paid off, and Maldonado has gone from their few acres in 2000, to more than 990 acres (400ha) today. They are now neighbors with the new vineyards of the Deicas and Bouza families, as well as an impressive clutch of new wineries making exciting coastal wines including Bodega Oceánica José Ignacio and Viña Edén. The biggest neighbor though, and one that has attracted major global attention to the region, is Bodega Garzón.

Argentine oil magnate and billionaire, Alejandro Bulgheroni, catapulted the region into the limelight in 2008, when he planted 593 acres (240ha) of vines—the biggest vineyard estate in Uruguay by a long mile—and started building one of the world’s most impressive wineries. Not willing to do anything by half measure, the US$85 million investment had one of the world’s top consultant winemakers on board, Alberto Antonini, along with one of the most skilled winemaking, agriculture, and marketing teams in Uruguay. “I advised Alejandro just to plant a few hectares, to see what worked in this new region,” admits Alberto, who manages Bulgheroni’s estates in Tuscany, Bordeaux, Argentina, and the US, too. “But he responded that he thought it was best to start with 200 hectares [500 acres]!” The team, in collaboration with Pedro Parra as their terroir expert, dug thousands of soil pits and mapped out more than 1,000 plots for vineyards across the 3,700-acre (1,500ha) estate.

Despite its explosive rate of growth, Garzón is very much at one with the nature of the region, maintaining the native forests and encouraging the native flora and fauna, even if the winery loses some grapes every once and a while to the roaming wild boars. It was also the world’s first Silver LEED winery and vineyard, which is no mean feat. “Ever since arriving to Maldonado in 2007, I’ve been impressed by the complexity of the environment,” adds Alberto. “I normally associate premium wines with biodiversity, and the Garzón region has forests, small bushes, palm trees, lakes, and many animals. It also has beautiful, granite mother rock and is situated close to the Atlantic Ocean, with these refreshing, cool and healthy breezes from the Ocean. This combination can give a lot of energy to the wines.”

This energy and vivacity of the wines of Maldonado, especially its lively Tannat, is what distinguishes them and is causing such excitement. It isn’t only Tannat, though that is making Maldonado stand out as one of the wine regions to watch in the New World; it is also its affinity for fragrant and refreshing Albariño, which almost every winery in the region has planted. Excellent Pinot Noir rosés are being made here (Bodega Oceánica José Ignacio’s is notable) and some really promising sparkling wines (Viña Edén takes the lead here).

Maldonado, as a new wine region, is a hub of innovation. But it also embodies some of the key trends that are driving Uruguay’s wine scene today: a focus on sustainability, an emphasis on the wine experience and tourism, and growing wine exports. Although Uruguay has had its borders closed for most of the pandemic-ridden past year and a half, as it looks to re-open, Uruguay is more ready than ever to be discovered by wine lovers. Its wine families and regions are ready to show what makes Uruguay stand out as a unique wine country of its own: proudly different from its neighbors and a gem to explore with both tradition and innovation at the fore.