Terry Theise brings his inimitable charm and perspective to the task of welcoming new drinkers to the sometimes baffling and intimidating world of fine wine—by jettisoning “the entire competitive matrix.”

We were six for dinner at home. One of our four guests was a wine pal, while another two were doctors, smart young people in a highly demanding profession involving years of education and training.

The wine I served was probably better than they were used to drinking, and though I tried to steer the conversation away from wine (as I tend to, unless wine is the reason for the gathering), I was asked the question I always get asked: “What can you tell us about this wine?”

The answer to that question has to be, “As little as possible, as much as necessary,” so I answered as briefly as I could, with only the most salient facts. One of my guests mused something along the lines of “Maybe we should learn more about wine,” which also tends to happen. That is where the ways diverge.

My wine pal jumped in excitedly, full of facts and figures and offering a tutorial on “how to taste,” and invariably, eyes started glazing over. While my wine pal was excited and eager, it sounded like “getting into wine” would be a lot of work.

All of us wine people go through a phase I call “showing what you know.” It happens because we’re jazzed by our discovery of this enthralling world, and we can’t help insisting how amazing it is, and we do this by regaling everyone with information. I know I did. Being a wine bore is a sort of awkward puberty for wine lovers, who (one hopes) eventually outgrow it.

Thinking back on that evening, I wondered why the wine world was such an unwelcoming place. I must clarify: I’m not speaking about the wine profession, which tends to be fairly welcoming (though until recently the warmest welcomes were extended to white males). What I seek to address here is the “civilian” world of normal wine drinkers, because I think we effectively dissuade them from feeling at home in our world .

Getting into wine

Wine, as we know, is in a state of malaise. Inventory pipelines are clogged. Restaurant reviews mention cocktail programs, but wine lists? Almost never. My local newspaper, in a sophisticated city with an outsized population of educated professionals, has discontinued what was already a mingy little wine column, some 600 words every four weeks. Wine writers have trouble finding work and even more trouble getting paid decently (if at all) for whatever work they do find. It is a troubled time for our favorite beverage.

Even for people who may be tempted to enter the world of wine, the closer they draw, the more forbidding it looks. It is intimidatingly dense with things-one-must-learn; it seems to involve an arcane skill—to become a “taster” and to cultivate a “palate.” The volume of data can feel overwhelming. Tasting notes can seem like the work of the deranged. Point scores suggest there is some absolute stratum of expertise one must slave for years to obtain. Wine education and the programs whereby titles are bestowed make the entire exercise feel like school. None of it looks like any fun at all. It’s going to make us feel inadequate. It’s probably going to be expensive. We’re going to need a bunch of tools, not to mention having the “right” wine glasses. Really, who needs it?

Yet here we are. Not enough of us, it seems, and we don’t appear to be terribly skilled at attracting more people to grow this little population. But I think there is a way—there has to be—to make this world feel warm and welcoming. It does not, emphatically does not, involve dumbing it down, and it must be sensitive about condescending to those less learned than we are. What we must do, I think, is remember our own pathways into wine; in effect, erasing all our accretions of knowledge and experience, and instead trying to tap into the ur-impulse that landed us here.

This is what I would have said to my doctor friends:

Nearly every person who “gets into” wine has had a moment of great pleasure, great fascination, or both, and this stirred us to opt into this world. Not very many people enter the wine world because they think it’s “a hobby” they should cultivate. Casual interest is likely to be frustrated. You need to have a big, slobbery crush on it, by which I mean that we make an emotional decision at first. And, even if one is less emotional, one can be charged with curiosity and intrigue. There’s not much space between “My lord, that was stunningly lovely and delicious!” and “Wow, how does such a thing come to be?” and most of us are pulled in by both impulses.

Personally, I would say we are drawn in by love first, and then by curiosity. If you remember only a single thing I’m saying here, remember this: Love will guide you to knowledge, but knowledge alone won’t guide you to love. Come into this world because it is blissful, and it will reward you beyond your wildest imagination, and it won’t feel like “work” unless you’re doing it wrong.

Wine doesn’t care how much you know about it. If you come into the fold, you go only as far as your own motivation compels. Stop whenever you feel like it; wine won’t disapprove. The bottles on the retail shelf will not cluck their tongues at you saying, “Oh dear, what a dilettante…” Maybe you’ll reach a point where you feel like you know what you’re doing, sort of, and that will suffice. Ride the impulse until the impulse withers. Yet—if you’re driven by pleasure, the impulse tends to remain vital, because pleasure is renewable, and wine is full of surprises.

Finding a map

But isn’t it awfully complicated, you ask?

Yup, it is. Beware of anyone who tells you it isn’t. They want your money. Wine is complicated—as are most of the things worth knowing.

Won’t you have to deal with wine snobs?

Sadly, yes. But there are snobs in many fields, and people who are already snobs will tote their snooty ways into this world, too. But wine doesn’t make them snobs. Chuckle at their ridiculousness, and go your own way.

If you’ve been propelled in by some transcendental experience (as I was, and as most of us were), you are eager for some sort of map (or GPS in the current argot) to help you along your way. Consider the following:

A few good, basic wine books. You need a reference. But start looking, and there are 300 wine books for you to consider—among them, my duo. But forget my duo. If they’re useful to you, it will be later on. What you need now are a few basic, reliable, entertaining reference works, among which none is better than The World Atlas of Wine, originally by Hugh Johnson and recently updated by the reliably companionable Jancis Robinson MW. If you had only one book, it ought to be this one. And if you wished to add, I’d advise you to favor the pithy and well written, which leads you to authors such as Karen MacNeil and Oz Clarke. You need a crutch at this stage, as we all did, and if you gotta have one, it should be one that’s well written and has a sense of humor.

Now you are armed with your eagerness and your reference works. Now what? It’s still a great heaving ton of stuff you have to learn. Or, “learn.” And there’s a reason for the scare quotes. You can decide to learn, you can set about learning, and, trust me, you’ll flounder. Or, you can follow your pleasure, and you’ll inexorably learn along the way. You can assist this process by:

Writing down what you taste. Pardon me, but it doesn’t matter what you write. You won’t show it to anyone. It is an exercise by which you think about what you taste and try putting it into language.

Language will frustrate you. English is not adequate. You’ll fumble around like we all do, even grizzled veterans like myself. You get as close as language lets you. And remember, this is so you will think about the wines you drink by dint of the effort to put evanescent flavor into intractable language. It’s hateful but useful. You’ll see.

But man, the whole thing is daunting, right? The way through is found in Anne Lamott’s immortal conceptualization. If you have to write a report on the “avian kingdom” and you stare at the page already defeated because it’s just too much, you break it down into chewable bits. You write it “bird by bird,” one at a time. It’s the same with wine. This isn’t like the hot-dog eating contest we Yanks have on the 4th of July. You don’t have to cram eight dozen hot dogs into your desperate mouth in 15 minutes. One thing at a time.

So—there are a number of grape varieties from which wines are made. Think about moving through them grape by grape. Or, there are a number of places from which wine might hail. Grape, place; place, grape. It leads you to three useful questions when confronting any given wine: Where is this from? What was it made from? What does it taste like?

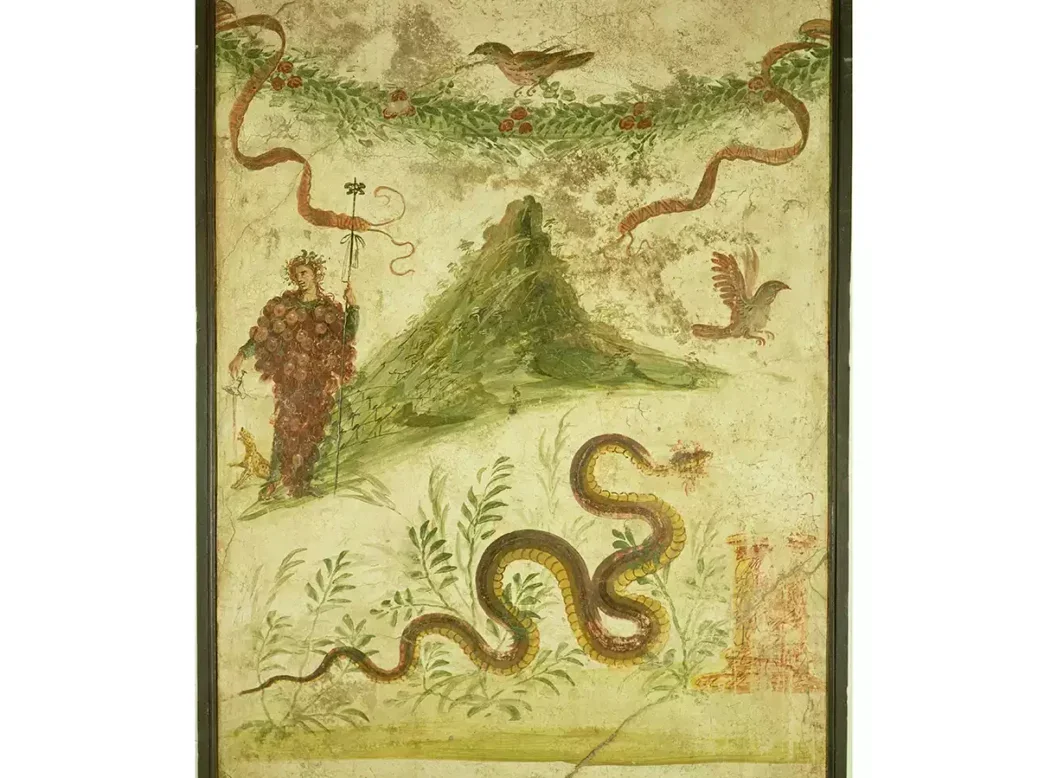

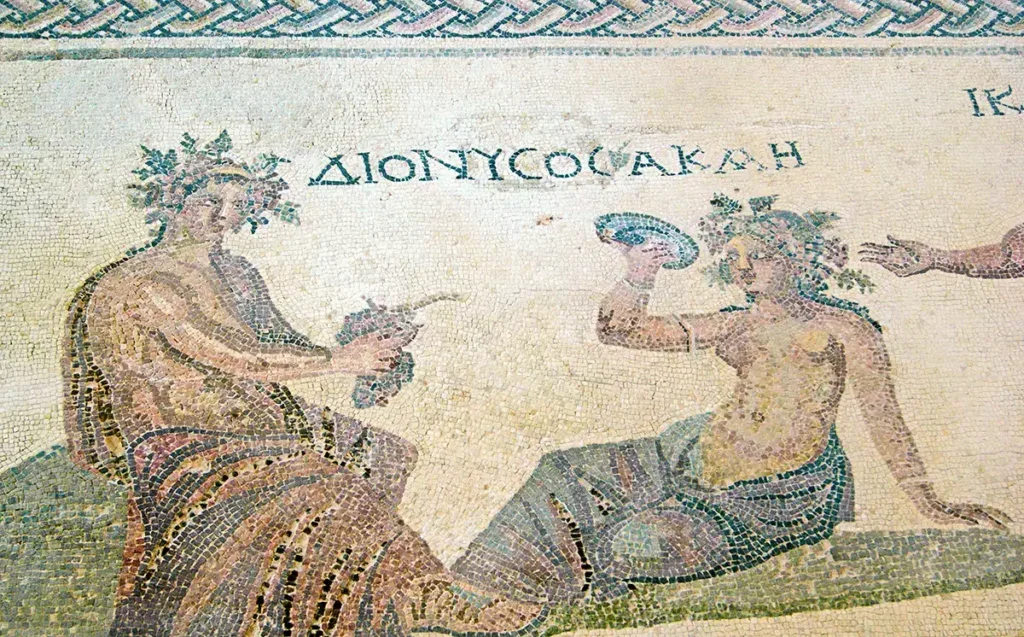

But here I must pause to remind you: If you’re someone who was propelled into this world, you will continue to seek that formative experience of wonder and joy and curiosity. You will find your way. And you will also start to see the reach of wine’s remarkable tentacles, which bear upon geology, chemistry, aesthetics, family and artisanality, history and culture, conviviality and generosity—to name but few. I myself believe wine is a glide path into the world of beauty, but we are free to tread upon the paths that are comfy for us.

The other fear to confront is the often-heard one: “I don’t know how to taste wine.” Here’s the good news: You do. You doubt me, but you do, you already do. Unless you’re one of the very few luckless people with a deficient sense of smell and taste, you are already tasting, evaluating, and judging. If you don’t believe me, here’s a simple exercise. Go to the grocery store and buy four different brands of tortilla chips (or potato chips, or whatever you like), take them home and taste them side by side, then consider which one you like best and, crucially, why.

Believe me, you are already a taster. You have a “palate.” Wine is just another thing to taste. It’s an intricate thing, at times, but no one is grading you on how many bits of intricacy you perceive. A “palate” is only partly the physical taste receptor; it is, saliently, a matter of paying attention over a period of time. If you drink wine twice a week for two years and you think about what you’re tasting, you will be amazed at how much you have learned and how much more developed your “palate” has become.

So, let’s pause and sum up. One: You come into this world because you are motivated by great pleasure and/or great curiosity. Keep on until you want to stop. Some of us never stop. Two: You have all the “equipment” you need to be a taster, as you will see. Three: You deal with the intimidating complications of the wine world by having a useful reference book and by breaking things down into digestible bits.

It’s hard if you need to “master” it. But only then.

It’s not only easy—it’s enthralling, if you let pleasure lead you. It takes time, but you have time. Indeed, you cease to perceive time, because you are so steadily delighted.

Jettison the competitive matrix

It helps to have a shaman. That’s a fancy word for a good retail wine clerk. That person is your very best friend. (S)he wants to make you happy so that you’ll return to buy more wine. Enlist this person as a guide. No one—not any writer or commentator—has a more vested interest in advising you well.

What of the sommelier? What indeed. With all the respect in the world for that profession and the people who succeed in it, talking to a sommelier is not how you learn about wine. Cue the hate mail…

First, it’s expensive. Second, it’s a social occasion, in public, with all the distractions of food and conversation. Third, it’s conducted under the eyes of witnesses. Dealing with the “somm” is a late-stage practice. And you’ll get there! But these excellent people will confuse the issue if you don’t understand their function. And I am very much aware of the many somms who do show sensitivity to their guest’s place along the wine-way, but even then, I’d advise you to be realistic about what they can and can’t do for you.

Speaking of expensive, sooner or later you are going to ask, “Is any wine worth thousands of dollars a bottle? I mean, it’s piss in two hours, right?” If you ask me, the answer is no. No wine is worth that kind of money, and the people who pay it are assholes whom you can safely ignore, except that they’ve bid the prices of many wines out of the reach of anyone not on the Forbes 100-richest list. To be sure, you can say a wine is “worth” whatever some idiot is willing to pony up for it, but that is an ugly, ugly world you want nothing to do with.

So, let’s pause again. Another useful principle: Don’t spend more than you can afford on a bottle of wine. It places too large a burden on the wine to justify your expenditure. You’re likely to be disappointed. Most of your great moments with wine will arrive unbidden and will surprise you.

That said, let’s say you’re exploring the wines of the Italian Alps. You have a bottle of Foradori’s Teroldego and you love it. You go back to the store, and the salesperson suggests the superior bottling, Granato, to you. Hmm, you think; it costs 60% more, but wow, that first wine was good, and this one should be even better. So you buy the bottle (and eat ramen that week), take it home and—then what? Maybe it blows you away. That would be great! Or maybe it’s… very good, but somehow you don’t “get” it. You will ascribe this to a deficiency of yours, but it is not. In the wine world, the relationship of cost to pleasure is unfixed and fluid. Maybe the Granato was too concentrated or too tannic or too inscrutable for you, or maybe you just preferred the volcanic twang of the “lesser” wine.

In a perfect world, your retailer-shaman would ask what you liked about the Teroldego and steer you away from the Granato and maybe toward some Lagrein or other. (And by the way, I use this example not to cast aspersions on Ms Foradori’s wines, which I happen to love.) I’m telling you this to reassure you: You do not have to spend more in order to be even more blissed out. It can happen, when all other things are equal, but you’ll find your way to those instances.

Finally, you “get” wine piece by piece. You need to be patient, but that isn’t difficult. You’re having so much fun along the way. Wine isn’t simple, but you can keep it simple by considering one bit at a time. It will add up. Wine wants you to love it. It’s people who get in the way. I think that the way to make this a more welcoming world is elemental, but it entails an attitude shift. You have to jettison the entire competitive matrix. When you start to do that, you’ll see how pervasive it is. But you have to do it if you’re going to encourage the fledgling.

Come in, it’s safe here; you’re already accepted, and you’re going to have a lot of fun.

Is that really so difficult?