Simon Field MW heads to Hungary for a tasting of wines from Royal Tokaji included a handful of 2018s, the first-ever vintage featuring all five of Royal Tokaji’s esteemed single-vineyard bottlings from Tokaj’s best crus.

Happy the country which grows it; happy the queen who gifts it, and happier am I who drinks it.” Who could have been describing Tokaji thus? There are many candidates, including Goethe, Beethoven, Bram Stoker, Voltaire, and a very fortunate Queen Victoria, who was gifted a case to celebrate her birthday—one case, that is, to celebrate every joyous year of her life. In 1900, she therefore received 972 bottles. Not bad. It could have been any of these admirers of the “Transylvanian elixir,” but it was actually Pope Benedict XIV, writing to the Habsburg queen Maria Theresa in 1750.

Hungary, yoked for centuries by the Ottomans, was a lesser partner in this tottering dynasty, later to be an even lesser partner in the relatively short-lived Austro-Hungarian Empire. Taking the “wrong” side during the Great War further diminished its status (and borders), and the 20th century was stained by Soviet occupation. This smallish landlocked country has always been vulnerable, strategically speaking, and has always looked to stand up for itself. It is happening again today.

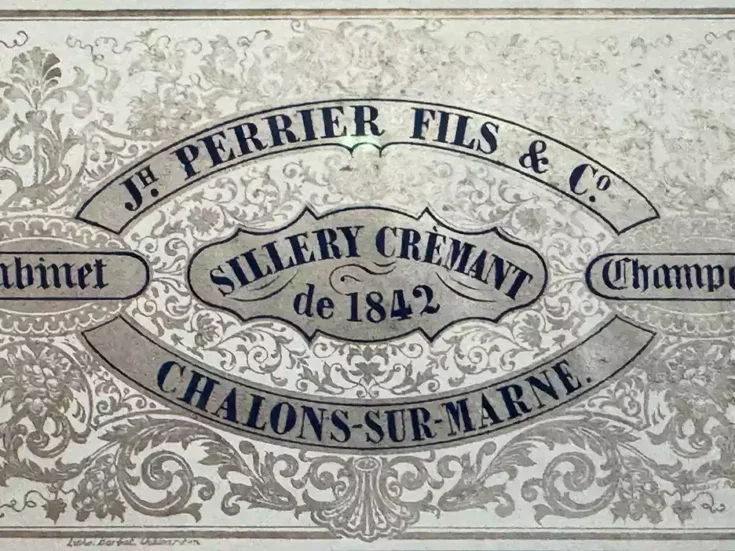

Some 300 years ago, its Protestant prince Ferenc Rákóczi II attempted to monetize the great asset that was Tokaji wine, thereby initiating a classification of merit that predated similar demarcations in Portugal and Bordeaux by 50 and 100 years respectively. There were to be 38 third growths, 59 second growths, and 29 first growths, of which two (Mézes Mály and Szarvas) were to stand out as first great growths. These wines were to be emblematic of the power and cultural heritage of Hungary as Ferenc, unsuccessfully as it turned out, attempted to pitch his great enemies (France and Austria, both Catholic) against one another.

The geopolitics may not have worked, but the wine taxonomy remains, forged by the rigors of terroir and the distinctive styles offered by a scenic patchwork of loess, clay, and volcanic basalt. At the center of it all is the dramatic and meteorologically significant confluence of the rivers Bodrog and Tisza in the town of Tokaj. The Tisza is gently colored by its yellow loess soil and flows in from Ukraine, one of the seven bordering countries, this one to the east of the great Hungarian Plain. Above us, punctuating the sky in black ink, we espy murmurations of starlings, pests to Royal Tokaji, which employs a ranger to shoot at them. We meet him at ten o’clock in the morning and he says that he has so far killed 50 birds. An incredibly beautiful pest when it flecks the sky thus, it has to be admitted—like Budapest itself.

Royal Tokaji: A special vintage in 2018

In 1989, Hugh Johnson, England’s greatest wine writer, decided it was time to rescue the legend—to restore the restorative, as it were—and to focus his efforts on the best sites as designated by the putative classification. 2018 is a significant vintage for Royal Tokaji (they call it their Royal flush), because it is the first year since 2008 that it has been able to offer all five of its single-vineyard wines, made up of four first growths and one second growth (Birsalmás). The year was hot and dry, the growing season advanced by up to three weeks, but the botrytis developed perfectly for the Aszú grapes, all of which were picked before the rain of early November. Wine director Zoltán Kovács—for whom 2018 is the second vintage after moving over from competitor Disnókő—is aware of both the quality of this particular vintage and of the company’s philosophy: “We have a responsibility to the region and to the preservation of the historical classification.” Herein lurks the paradox of being able to discern stylistic differences despite the high levels of residual sugar, which one may have suspected of imbuing a degree of anonymity. Not at all. The Birsalmás is typically smoky, the Betsek spicy, the Szt Tamás reticent, and the Mézes Mály honeyed and rich. The hot, dry vintage has done little to undermine such evocation—quite the contrary. Even the etymology of the vineyards comes to our aid: Birsalmás, the word, means quince orchard, and it is fair to say that the wine is reminiscent of quince jelly. Not a quince in the vineyard, of course.

The wines have been made traditionally, with the Aszú grapes macerated and therefore rehydrated for two days with fermented must from base wines with the same source, thereafter pressed and racked to barrel (300 and 500 liters these days, more of it new than previously) and left for two years in the ancient cellars (the Wine Chapel is a temple of black mold and stooping damp), then another three years after bottling. The 2018s have thus been released in 2024. We are advised that there is to be no Essencia this year, so the few modest tears of liquid eased out by gravity have been blended back. The current release of Essencia is the 2016, which notched up 535 grams of sugar and a somewhat parsimonious 2 degrees of alcohol. It is safe to say that one does not discern much by way of terroir in the Essencia—but who needs terroir when one is in the presence of the elixir of life itself? Reading a Berry Bros pamphlet sent out in the 1920s, it becomes clear just how the mythology of Essencia had spread: “Send me a case of the wine which removes the screws from the coffin lid,” wrote one customer.

The best vineyards, focused on the three key areas of Tokaj, Tarcal, and Mád, all offer distinctive wines. It will henceforth also be interesting to track the progress of the dry wines, now also offered (albeit it in extremely small volumes) by single-vineyard bottlings. A fascinating development. If only the holdings (scattered, in most cases) were a little larger. There is a definite sense of anticipation in these villages, punctuated by silent building sites that appear primed to extend the Habsburg gold and to revitalize yet further a region that has already made significant progress, all things considered, since the dark days of the collective farming (Borkombimat) and a homogenized family of dull, oxidized wines, most of which were sent to Russia in exchange for natural gas. The fact that early investors such as AXA Insurance (Disnókő) and Vega-Sicilia (Oremus) are still present, making significant strides, bodes well, even if the current regimen in Budapest is not always entirely helpful when it comes to international trade. Where is Prince Rákóczi when you need him? Tokaji is a potent symbol, gilded qualitatively and stylistically, and its progress from romantic nostalgia to commercial realism, now firmly in train, should not and will not lose sight of the glories of its past.

Tasting

Held at Royal Tokaji in Mád, with Zoltán Kovács, October 2024

2021 Szt Tamás First Growth Dry Furmint (RS 2g/l)

One of our fascinating tastings addresses the increasingly important dry-wine category, with single-vineyard examples, all made in extremely small volumes. Brought up in oak, a third of which is new, and informed in personality by both flor yeast and a lack of sulfur, this is an intriguing and hopefully important development. Linden, dried flowers, thyme, and distinct yeast notes on one level, but then, with air, hints of pineapple and spring flowers. Big-boned and flinty but far from skeletal, as an innate generosity is teased from the robust structure. If, logically, sugar may well obscure the terroir up to a point, then these drier wines are well placed to give it a fuller expression. Indeed, the 2022 Szt Tamás was very different, richer and fuller, though this may have been a function of the warmer vintage. Finally, a dry Betsek from 2021 is more linear, and intrigues with a distinctive elderflower aromatic. Fascinating wines all; these single-vineyard dry wines show great promise, even if their volumes will inevitably be modest. | 92

2018 Gold Label Tokaji Aszú 6 Puttonyos (RS 197g/l)

Mid-gold, with immediately attractive aromas of quince paste, dried fig, and saffron. Medium intensity, with acidity hallmarked into a beguiling structure. Hints of tropical fruit and then vanillin to betray the higher proportion of new oak (rising to 40% with the single vineyards in this vintage), itself key to the more modern face of the brand. Janus-like, however, the wine forsakes neither heritage nor provenance; and if anything, its robust structure serves merely to add focus and to highlight the volcanic acidity at its heart. | 92

2018 Birsalmás Second Growth Tokaji Aszú 6 Puttonyos (RS 187g/l)

With a name meaning, evocatively and possibly at one point accurately, quince garden, Birsalmás is the only second growth in this privileged family and is also, coincidentally, its smallest vineyard; a complex tapestry of loess-clay and volcanic topsoil. A small proportion of the pulpy, gregarious grape Kövétszőlő is co-planted with the Furmint. Deliciously fragrant, with plums and mandarin to the fore; thereafter, tangy, smoky, focused, and seductive. | 93

2018 Szt Tamás First Growth Tokaji Aszú 6 Puttonyos (RS 199g/l)

Zoltán’s favorite (he describes it as the non plus ultra of Tokaji and also refers to its “naked purity”), Szt Tamás rejoins red clay with indigo volcanic rock and is devoted entirely to the Furmint grape. The 2018 is initially a little reticent but then glides with silky authority, carrying bittersweet Proustian notes before it in a stream of evocation and pleasure. Stem ginger, quince, dried apricot, nutmeg, and wasabi—but a few descriptors from an encyclopedic array. There are herbal and savory undertones here—gastronomic potential, therefore—yet the ensemble manages to remain light on its feet, diaphanous, balletic… Delightful, in short. This is the one that needs the most time, per Zoltán. | 95

2018 Betsek First Growth Tokaji Aszú 6 Puttonyos (RS 197g/l)

Hárslevelű joins Furmint here as a minority shareholder. Habsburg gold, noble. There is a floral note to the nose; jasmine maybe, then hints of rosemary and white pepper. Betsek is distinctly spicy, with clove and cinnamon neatly wrapped in vanillin, stern acidity holding the ensemble together. As usual, Betsek shows very well in youth. Soft honey and green tea vie for attention on the finish. | 94

2018 Nyulászó 1st Growth Tokaji Aszú 6 Puttonyos (RS 205g/l)

Etymologically “a good place to catch hares,” Nyulászó is also, clearly, a good place to grow grapes, Furmint and Hárslevelű in this instance. The wine is poised and precise, yet slightly smoky on the attack and unerringly complex thereafter, combining savory, umami notes (cèpes and white truffle) with tropical elements, all entwined in a taut, tense ensemble (the famous “Tokaji tang”) and with what Hugh Johnson memorably describes as “a finish as long as the Danube and as lively as Liszt.” Indeed. | 96

2018 Mézes Mály Great First Growth Tokaji Aszú 6 Puttonyos (RS 207g/l)

One of two vineyards designated for the top “great first growth” category, Mézes Mály slopes the outskirts of Tarcal and espies the great Pannonian Plain beneath and beyond. Deep loess tops the volcanic bedrock and lends rich textural depth. The wine is broader, sweeter, and more demonstrative than its peers, with notes of linden, poached pear, kumquat, peat, and quince jelly underwriting its tight structure. There is even a phenolic austerity at the back of the palate, once again underlining breadth of dimension and extent of ambition. The name of the vineyard translates as “honey place,” and honey pervades the edifice, with dried apricot and peach pear providing elegant support. | 96

2016 Essencia

(RS 535g/l)

Although not a formal part of the 2018 launch, self-evidently, the opportunity to taste the elixir of life is seldom refused. With a mere 535g of residual sugar and 2% ABV (interestingly the 2008 scaled the dizzy heights of 4%), this is a blend—for want of a better word—of Furmint, Hárslevelű, Yellow Muscat, and Kabar that was bottled in 2019 and released in 2023. Rhubarb, meddler, quince, and cherry are the first descriptors to ooze from the taster’s pen. Thereafter, the gentle caress of perfection takes hold—if a caress is permitted such abstraction! Restoration. | 96