With its wines made from Cabernet Franc in Saumur-Champigny and from Chenin Blanc in Anjou, Clos Rougeard represents “all that is good about the Loire,” says Simon Field MW.

It was from Chinon rather than the marshes of Aquitaine that Henry II of England, in 1150, made a valiant attempt to carve up western France and to salvage, at the very least, the legal gift of his marriage to Eleanor. Peter O’Toole and Katharine Hepburn capture the tension rather well in the film The Lion in Winter, with England’s hegemony at stake and France’s honor at risk. What better backdrop than the mighty Loire, which snakes through the “garden of France,” its 300 châteaux fortifying the route and serving as a poetic reminder of the significance of a region that has long served as a retreat for the aristocracy and playground of the affluent? And, of course, as the source of some of France’s most subtle and nuanced wines.

One of the châteaux that Henry chose to restore and further fortify was on the south bank of what is now the town of Saumur, a modest conurbation of 26,000 people that lies between the larger towns of Angers and Tours. Famous for its tank museum and equestrian school, Saumur was, somewhat surprisingly, the birthplace of Coco Chanel. Its château also imprisoned the Marquis de Sade and inspired Balzac’s Eugénie Grandet. Furthermore, it is celebrated for its wines.

Saumur is normally grouped with Anjou when it comes to categorizing the Loire Valley, thereby placing it at the center of the triptych that is hinged by the panels of Muscadet and Sancerre, among others. Anjou Saumur is, needless to say, complicated, with a healthy quota of ancestral grape varieties (Grolleau, Gamay, Pineau d’Aunis, and the like), as well as a buoyant legacy of sparkling and rosé wine production. Our focus here is on the most planted and most noble of varieties, Chenin Blanc and Cabernet Franc, and on the town’s most celebrated producer, Clos Rougeard. Representing all that is great about the wines of the Loire Valley, Rougeard dedicates its production to monocépage, with one white wine made under the appellation of Anjou Blanc and three red wines that all fall under the jurisdiction of Saumur-Champigny. A small but consequential appellation, which covers a mere 1,500ha (3,700 acres) along a plateau of tuffeau (of which more later), Saumur-Champigny is located between Saumur itself and, farther to the east, the town of Montsoreau. The wines are paragons of purity, thus far at ease with climate change and with distinct and memorable personalities. The property is described by its new owners, Eutopia Estates, as a “singular mythical domaine,” for once not the overstatement of a proud new parent. The wines of Clos Rougeard are always fascinating, especially when compared with the best examples from neighbors Bourgueil and St-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil. And then, why not, with the other great Cabernet Francs and Chenin Blancs of the world.

Clos Rougeard: Rooted in revealing the truth of terroirs

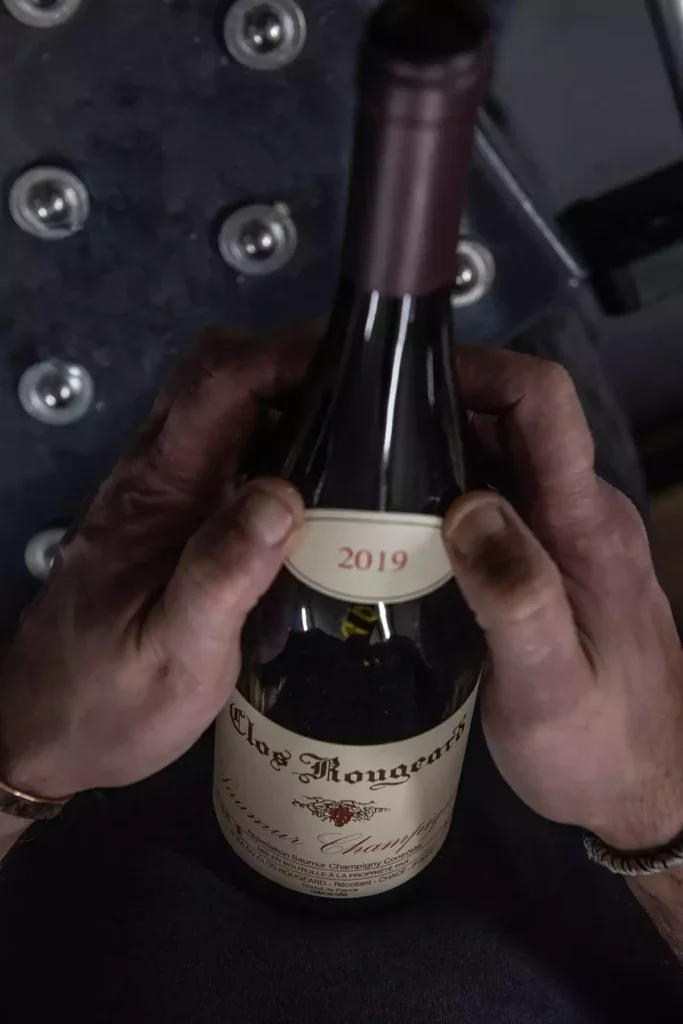

Clos Rougeard is based in the village of Chacé, just outside the town. Production is modest, usually between 40,000 and 50,000 bottles per annum; the wines, as we have seen, are steeped in the virtues of the varietal but also of the single vineyard, with three reds and one white in production, all of which also respect the great virtue of patience and are released five or six years after the vintage. A dazzling quartet of 2019s is now emerging, therefore. If, however, one is expecting Azay-le-Rideau architectural grandeur in deference to reputation, then one will be disappointed. The winery, formerly used by the Compagnie des Grands Vins to make sparkling wine, was purchased as late as 2010 and has steadily been refurbished (slate and pine and modern art), with the latest addition a new family of 46hl vats, their size focused on emphasizing the nuanced differences between the plots. Pragmatism meets poetry head on, and the beauty is mainly in the bottle.

For eight generations, the domaine was run by the enigmatic Foucault family. Legendary in situ tastings and a suitably gnomic interface with the media forged a reputation not unlike that of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti in Burgundy or, even more apposite, Château Rayas in Châteauneuf-du-Pape. From 1969, the property was run by charismatic brothers known as Nady and Charly (real names Bernard and Jean-Louis), the latter so named because he apparently bore a resemblance to local saint Charles Foucault (no relation), who was canonized for curing a woman who had impaled herself on the railings of L’Eglise St-Pierre in Saumur. There was no longer a clos, no grand winery to show off, and as it turned out, there was no clear line of succession to carry the family into the ninth generation of Foucault ownership. In 2017, the property was sold to the Bouygues family, best known for telecommunications but also, latterly, for purchasing and reawakening two famous wineries in Bordeaux: Châteaux Montrose and Tronquoy in St-Estèphe. Clos Rougeard has joined a family that also includes Domaine Rebourseau in Gevrey-Chambertin and RdV Vineyards in Virginia, not to mention a prestigious truffle farm, also in the Loire Valley. No lack of pedigree, then, with the bonus of genuine familial involvement (especially from Martin and Charlotte Bouygues), an involvement that does not extend to intervention in the modus operandi. The latter is left to the new (employed in 2023) estate manager, Cyril Chirouze, who joined Rougeard from Château des Jacques in Moulin-à-Vent. Overseeing all of the properties is Pierre Graffeuille, who is the general manager of Eutopia Estates and also closely involved in the winemaking at Château Montrose. The holding company is well named, it seems, and according to Pierre, has its philosophy “rooted in revealing the truth of terroirs”—a philosophy that he has certainly already put into practice at Château Montrose, judging by the phenomenal quality of its recent vintages.

Cyril’s philosophy is equally clear: “We are pioneers, but we never proselytize,” he says, citing specifically the respect for the single plots and the extended aging as two examples where laissez-faire can also be interpreted as a genuine respect for the terroir in question. Viticulture has followed a similar template, with only copper and sulfur, both used modestly, buoying what is essentially an organic approach. As for biodynamics, this extends to observing the tides and the moon but has not progressed as far as applying a cocktail of preparations to the land. Let the land do its own talking… Cyril maintains that he has merely helped the natural process. L’esprit paysan of the Foucaults may have tried for microvinification by dividing the big vats in half; Cyril has made the decision to replace the large vats with smaller ones, which seems logical enough. Such are the advantages of benevolent ownership.

Simplicity of purpose and purity of product

Clos Rougeard covers 15ha (37 acres), with its four key labels spread over 20 plots. The soils are essentially clay and limestone, with a sandy topsoil; they differ subtly because the vineyards themselves are not contiguous but are all based in and around the small village of Chacé. In 2023 and 2024, a total of 2.6ha (6.4 acres) were acquired, small plots adjacent to both of the key vineyards (Le Bourg and Les Poyeux)—very fortunate purchases, according to Cyril, especially the one at Le Bourg, which is otherwise surrounded on all sides by the houses of the village. One thinks of Pessac-Léognan and is reminded of the etymology of the word Bourgeois.

Relatively finite in scope, then, and relatively unchanged over the years. Of the three red wines, Le Bourg and Les Poyeux are site-specific, the former more foursquare in style, the latter more silky. And then there is a blend, Le Clos, which borrows stylistically from both. The white wine is made from Chenin Blanc on a nearby plot at Brézé, which was bought in 1993; here there is a little more clay and north-facing vines on a slight incline. All four wines are vinified in concrete vats and then aged in barrels of differing age and provenance (there is a little kiss of human intervention), and are all maintained at a constant temperature in the tuffeau cellars beneath the winery. The new capacious installation fulfills the need for storage capacity for bottle aging, since the wines are not released before their sixth year.

All relatively straightforward, with simplicity of purpose and purity of product key goals, as they always have been. A visit to the vineyards underlines the differences, however; Le Bourg is flat, urban, almost claustrophobic, whereas Les Poyeux is gently elevated, cushioned by a forest and bucolic. Does this mean that the wines themselves will pitch poetry against prose? Not at all, but the differences are immediately obvious. Les Poyeux’s 4.3ha (10.6 acres) comprise well-draining, aeolian sandy soils (one thinks again of Rayas) on a gentle slope; Le Bourg, first produced in 1988, now covers 3ha (7.5 acres), its soils consisting of a shallow, clayey silt (30in [75cm]) over a Turonian chalk terroir. Furthermore, the élevage for the two wines also differs, with Les Poyeux aged in barriques from Bordeaux (two years in one-year-old wood), and Le Bourg in barriques sourced more locally (two years in 80% new wood). To what extent, one may debate, do the differences (floral and silky versus more robust and powerful) derive from the sites as distinct from the subsequent élevage? An early tasting of the 2024s demonstrates that the differences are well embedded even before the oak has had an opportunity to forge a “new” identity. And for completeness, it should be noted that the Les Clos blend (15ha and 15 plots) naturally enough combines both of the soil types mentioned above and is also aged for two years. The white wine, Brézé, is located in the eponymous village and covers 1.5ha (3.7 acres), its soil, as observed, more influenced by clay. The wine is aged in barrels made by the cooper who also provides for Le Bourg, this time for a year only, with only 30% of the oak new. All the bottled wine is aged thereafter before commercial release, innate complexity given time to underscore itself four times over.

The best way to understand such subtle differences is to taste the wines at different ages, first from barrel, then from bottle, with an older example added for good measure to assess evolution. Down, then, to the tuffeau cellars beneath the winery. Unlike the cellars in Champagne, there is little by way of dazzling chalk; more the soft (lichen) green-gray of this distinctive and distinctively porous material. Tuffeau, it seems, was formed during the Turonian Era (hence Touraine) and melds sand, marine fossils, and porous rock. The barrel samples from 2024 have just completed their malolactic fermentation and are hard to judge. According to Cyril, 2024 is very much a “classic” vintage, cool and crisp, with an early budding and a long growing season, frost the most pressing concern early in the year and some aggressive mildew later on. In Cyril’s opinion, the vintage demonstrates that the concept of “global warming” needs to be addressed with caution; climate change, for sure, however, with the early cycle especially challenging. Cyril has not used candles to fight the frost but has added an electric heating system to the Guyot cabling in the Bourg vineyard to combat the latent risk. It was even more problematic in Bourgueil, Cyril reveals; Champigny, etymologically, describes “fields of fire” (Campus Igneous), which correctly implies a warmer microclimate. The wines, in any event, are succulent, lifted, and rich—Les Poyeux with aromas of blossom fruit and spice; Le Bourg offering an intriguing juxtaposition of saffron and juniper… à suivre. The white wine is taut, with the firm, citric acidity typical of Chenin at this age, and a beguiling floral aromatic that is still somewhat phased by the wood.

Next up are the 2023 reds, now in their second year in wood. Cyril describes 2023, his first year at Rougeard, as “a baptism of fire.” He does concede, however, that Cabernet Franc does not fundamentally differ so greatly from Gamay, his partner at Château des Jacques for many years. 2023 was warmer than 2024, but nowhere near as warm as, say, 2022 or 2018. Frost was again a problem, as was intermittent and unpredictable rain, with significant precipitation late in the spring, then toward the end of August and also in early September, with little by way of an Indian summer to protect the harvest. The results impress, however, and the difference between the sites is once again underlined. Les Poyeux has a lifted, summer-pudding aromatic, with dark spice and ripe, generous, and silky fruit. The oak is discreet, none of it new, all of it highly prestigious (from Montrose, Angelus, and Figeac, no less). By way of contrast, Le Bourg, which has seen new oak, is muscular and energetic, its dark fruit velvety and textured, its spicy peroration clearly touched by the wood. Cyril cites the structure of the soil—with its firm clay limestone base—as the explanation for this contrast, revealing that the use of the more locally sourced wood is intended, almost paradoxically, to give a more Burgundian feel to the wine. Structured and yet elegant, too; the best of all possible worlds. The vines have yielded more than 45hl/ha for this wine, which is reasonably high for Clos Rougeard. Le Bourg is the site of the original clos (the wall has been subsumed into the urban matrix), and it was here that the brothers lived and here that they entertained heroically, the wines from 1934 and 1923 especially appreciated. Here, in other words—and despite the flat, prosaic perspective—the legend was born. It is little wonder that there was a wish to commemorate the fact by instigating this superb stand-alone cuvée in 1988. On occasion, one has to dig a little to unearth the legend, in this case through sand, limestone, and clay, and through decades of husbandry that have eschewed the intervention of herbicides, pesticides, and the like, giving a full and glorious expression to the enigmatic Cabernet Franc grape.

Crafting the finest wines possible

Into the warmth of the tasting room now, and a preview of the quartet of 2019s, which are about to be released. As in many parts of France, 2019 was born nobly and has, if anything, been gaining in reputation in the interim. It is a vintage not untouched by warmth, but with a measured, temperate classicism in evidence, which is of special relevance to tannin management. For Pierre, both the individual vintages and the individual sites need to be assessed separately; he describes the process in terms of haute couture, with attention to detail key and allied to the need to know when to do nothing. This, the “paradox of the pioneer,” is especially relevant when one is vinifying by parcel. The needlework of detail often hangs by a narrow thread, but behind it all will be fundamental decisions on such things as the timing of the harvest (nature has been capricious of late) and the temperature of the fermentation vat. In terms of extraction, Cyril favors more time (a month at least) and less intervention. He describes a gentle mouillage du chapeau (wetting of the cap) rather than anything more energetic, in order, he says, to “homogenize the yeast”—the latter, needless to say, natural. Elsewhere, gravity assistance and a regimen of minimal sulfur additions both serve to underline the non-interventionist approach. In a region where the monastic heritage has been less marked in the vines (surprisingly, one may surmise), it was down to visionaries like the Foucault dynasty to write the vinous lore. There is the Abbaye de Fontevraud nearby, Cyril says, and evidence that the monks did indeed plant Cabernet Franc, but perhaps without the pedagogic zeal of their Burgundian brothers. Or maybe here a story remains untold… The Abbé Breton, this time from the Abbaye de Bourgueil, did, after all, lend his name to one of the many synonyms for Cabernet Franc. Once again, the misty Loire is shrouded in enigma.

Back to the 2019s, which are now entering the marketplace. An excellent vintage, pace Cyril, yields concentrated by early frost, thereafter never too warm; overall very dry, but with just enough rain at just about the right moments. These youthful samples are starting to open up and are all marked by concentration and complexity.

This is a very fine quartet, and the 2015 Les Poyeux with lunch only heightened the enigma, such was its approachable power. The child of another “modern classic” vintage, the wine was intense in color, aroma, and taste, wonderfully complex, and well suited to the accompaniment—veal, in my case.

The Bouygues family has no intention to expand either the range or the modest holdings; the laissez-faire approach that underwrites the winemaking so successfully looks set to preserve the overall framework. This is refreshing, especially when one considers the demand for these wines. The philosophy of the Foucault brothers and their long line of forebears is safety instilled in the new owners, who have not the slightest inclination to transform Clos Rougeard into another Château Montrose. Both, however, enjoy the attentions of diligent and sensitive winemaking, as well as a fascination with the Cabernet Franc grape variety. Pierre Graffeuille is elegant and spirited in describing Clos Rougeard and its challenges, praising in particular the domaine’s “exceptional plant material and deep expertise in massal selection.” He adds, “We do everything we can to listen to our terroirs and to craft the finest wines possible. And all with exacting standards and great humility.” Prospects for Clos Rougeard are promising indeed; the lion is revitalized and ready for the spring…