Anne Krebiehl MW attends the London edition of Champagne Louis Roederer’s 50th anniversary celebrations of Cristal Rosé, where the line-up of remarkable wines was a fresh reminder of the house’s insatiable appetite for improvement.

Of all prestige cuvées in Champagne, Cristal holds a special place. Not just because of its history, having been created in 1876, or because it embodies luxury—that, too—but because it exemplifies a progressive spirit. This is even more apt for Cristal Rosé—probably the most contemporary take on Champagne right now—marking its 50th birthday in 2024. The invitation to celebrate half a century of Cristal Rosé at Mauro’s Table at Raffles London in early October was therefore unmissable. Both Frédéric Rouzaud, CEO of Champagne Louis Roederer, and Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, the house’s visionary cellar master, welcomed us to this memorable lunch. Rouzaud said it was “one of the most unique meals I could have, with so many vintages of Cristal.” We tasted the wines in pairs: 2013 and 2012; 2008 and 1995, 1989 and 1976—followed by the 2002 Cristal Rosé Vinothèque—all in magnum bar the Vinothèque, all the original disgorgements.

50 years of joy and wonder

It was Jean-Claude Rouzaud who created Cristal Rosé in 1974. “I pay tribute to my father Jean-Claude, who—82 years old today, 32 years old then—was just put in charge of winemaking,” said Frédéric Rouzaud. At the time, the house was run by Camille Olry-Roederer. Jean-Claude was the grandchild of her first marriage, and when he joined the house in 1967, Camille decreed that he should look after the vineyards; she clearly had no cushy office job in mind for her grandson. This, said Rouzaud, “was a good thing,” since it reinforced that link between vineyard and cellar. Jean-Claude became winemaker in 1974, the year Cristal Rosé was born. Not only did he manage to give “new levels of fragrance, of energy, of nuance” to the wine, but he also, Rouzaud emphasizes, “laid the foundation of innovation. He put vines at the center of the process with the first vineyard selection, a historic plot that is also the foundation of our massal selection” and introduced “a new technique called infusion, evolving growing practices and emphasizing the terroir. We now have more than 240ha [600 acres], and there is a constant link between the vineyard and the cellar.” Today, this link is stronger than ever, but it was unusual then. Pink Champagne was also unusual. Rosé represented a tiny sliver of Champagne production—for one thing, rosé was harder to make in cooler times; for another, rosé Champagnes, just like rosé wines, were then taken far less seriously. Hubert de Billy of Pol Roger told me some years ago that it was once considered the “wine of the demimonde.” Frédéric Rouzaud concluded his welcome with a fitting summary: “Half a century after the creation of Cristal Rosé means 50 years of improving and innovating, of evolving and exploring—50 years of joy and wonder. Happy birthday, Cristal Rosé.”

The DNA of Cristal

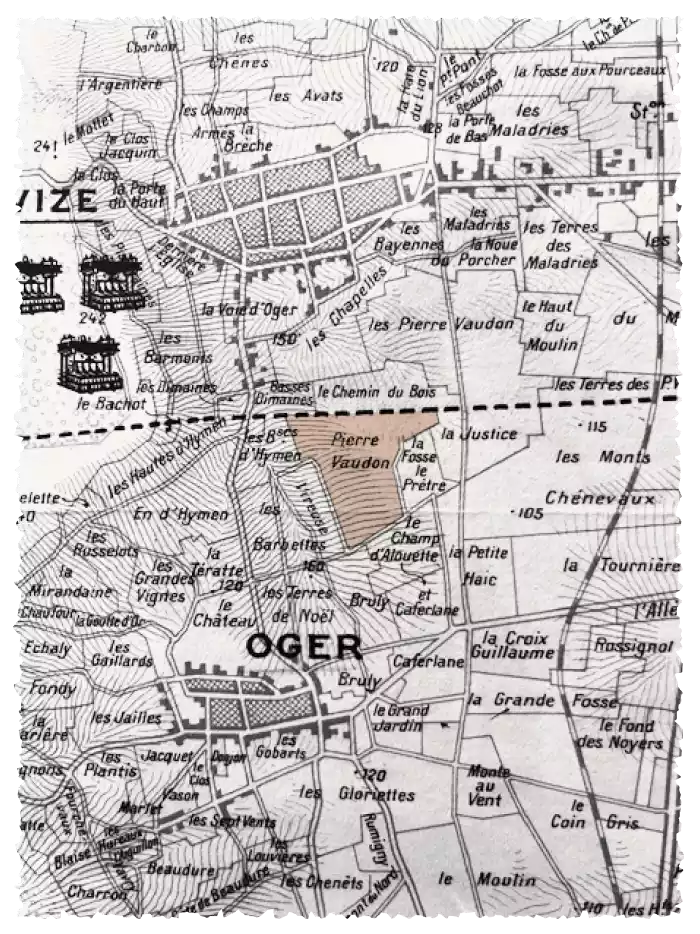

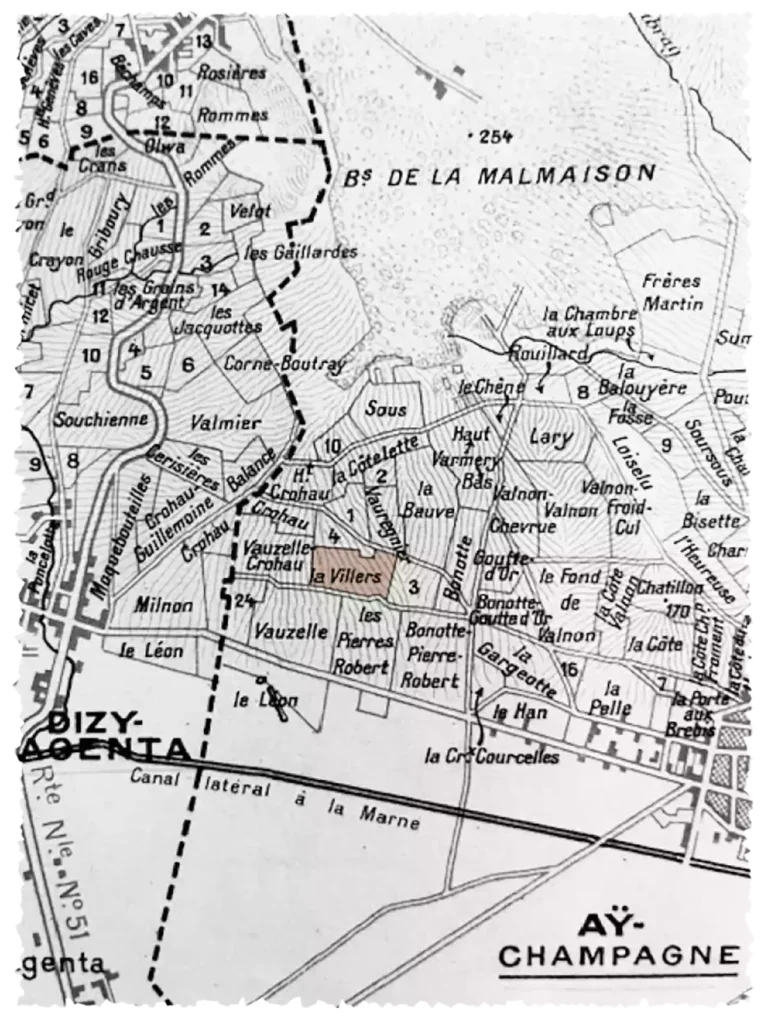

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon then introduced the first pair of wines, confessing that he had debated whether to start with the oldest or the youngest wines. He decided to start with the most recent, “because the youngest wines embody all the ideas in the vineyards and the dedicated plots that are part of Cristal Rosé. Jean-Claude understood in 1974 that Champagne meant to put the wine back into the vineyard.” Today, there are five plots that are dedicated to Cristal Rosé. Three are in Aÿ, and Lécaillon referred to these south-facing sites as the “Musigny of Champagne,” a comparison that has now gained currency among his Champenois colleagues. These three plots are Gargeotte, Bonotte, and Villers. These have “a very special phenolic quality; they are not just more saline, more complex. We’ve always found that these plots were effortlessly precise. Saline, but not too saline; tannic, but not too tannic, and so effortlessly aromatic.” Lécaillon noted that Jean-Claude Rouzaud kept these separate from the rest of the domaine, preserving “the original massal selection” of which Lécaillon extracted more than 150 vines for observation and propagation from 2000 onward, which now constitutes a sort of Cristal DNA. In 2013, Gargeotte and Bonotte were pulled up and replanted with these preserved Pinot Noir genetics at a density of 13,000 vines per hectare, work and progress that goes to the very heart of Cristal. Its two Chardonnay plots are Pierre Vaudin in Avize and Montmartin in Le Mesnil-sur-Oger. “The idea of Cristal Rosé is to be in pursuit of phenolic ripeness that is integrated with Champagne saltiness, Champagne elegance, and Champagne finesse,” Lécaillon said.

Fruit, sunshine, and soil

Lécaillon commented on each vintage pair: “2013 was a late-ripening October harvest; a long ripening period, which we like a lot. The fruit [in the wine] is the same as it was 11 years ago; it has eternal youth,” he remarked. “2012 is the riper vintage; richer and juicier as well, with perhaps a little more Pinot Noir influence. The mousse—I insist on this—in Cristal is not bubbles of carbon dioxide but bubbles of salt. It shows so well in the 2012.” He noted that when drinking Cristal, “the first ten years are about fruit and sunshine; after ten years, the soil comes back.” The wines are a striking pair—the 2013 tightly coiled, and 2012 exquisitely expressive, just hitting its stride. Mauro Colagreco’s subtle dish of radish and langoustine tartare, with its inherent sweetness and saltiness of the crustacean, underlines and emphasizes the characters of 2013 and 2012 beautifully, amplifying each vintage character.

An unusual way of making rosé

With the following pair of wines, 1995 and 2008, Lécaillon explained the evolution of making Cristal Rosé. “Jean-Claude wanted to co-ferment, bringing a wine that is more ethereal, more precise, more integrated—an infusion,” Lécaillon said, explaining how he took Rouzaud’s “infusion” ever further. Ever since 2008, “we have a very cool infusion,” he said. All the grapes are hand-picked. The Pinot Noir bunches are kept overnight at 25°F (–4°C), “so they become very crunchy. I believe that cooling the phenolics makes you catch the good phenolics.” The cold grapes are then sorted, destemmed completely, crushed very gently, and left to come up to normal temperature again over six to seven days, initially protected by dry ice (frozen carbon dioxide), later on by nitrogen, to prevent oxidation. Once the juice is just about to start fermenting—Lécaillon observes the yeast populations in the must closely—the juice is racked but the grapes are not pressed, so there is only free-run juice. “During this process,” Lécaillon explained, “there are different infusions.” This means that after four days, he might rack some of the Pinot Noir juice and mix it with Chardonnay juice to co-ferment. “Co-fermentation works so well because Pinot Noir is oxidative and Chardonnay is reductive, and this captures the aromas,” he said. He will rack more Pinot Noir juice at several points for more such co-ferments and will end up with tanks of various co-ferments. In the winter following the fermentation, he chooses which of these is the best. “In some years, it is the first; in some it is one of the later co-ferments,” he noted. For him, 2008 represents “a new era of Cristal Rosé.”

Lécaillon noted that the 1995 was, in a way, “the last of the 1970s,” meaning the last wine made with a legacy of older thinking and older habits. “We were not yet in the cold-soak-phase,” he explained. “Why? The 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s had more botrytis years, so you had faster infusions,” noting how much the sanitary state of the grapes via farming—especially via organic and biodynamic methods—and the stringent selection have been improved. “These two wines really are the showcase of the two kinds of people living on the land. 2008 is a version of nature that is soft, that works hand in hand. In 1995, we were still in the age of thinking we are above nature.”

The identity of Champagne

Lécaillon had chosen the final pair of wines, Cristal Rosé 1989 and 1976, to make a point. “Because we speak about Champagne being very warm and maybe losing its identity over time,” Lécaillon said, “I chose two hot vintages. Both were picked at 11% potential alcohol. 1989 was picked on September 5; 1976 on September 1,” he said, adding that “if 1976 was today, people would have picked in mid-August because of acidity. Both are very fresh but are low in acidity. Freshness comes from somewhere else, from phenolics, from dry extract.” Then there is the fact that 1989 was Lécaillon’s first vintage in charge at Roederer. He remembers that they “had no cooling system at the time; we just sprayed the tanks with cold water. We hired some reefers [refrigerated containers], and by mistake we created the first cold-soak, and this really inspired me.” About 1976 he was succinct: “1976 certainly is the best Cristal [of the early years]—better than 1974. Jean-Claude was on target with ’76, we have this beautiful phenolic ripeness.” The evolved flavors of the wines prompted Lécaillon to note that he prefers to have as much post- as pre-disgorgement aging. “Time on the lees is umami time, amino time,” he noted, when aging on lees creates the umami flavors of autolysis. Post-disgorgement aging, on the other hand, was for him “Maillard time,” referring to the myriad flavors created by Maillard reactions between amino acids and sugars over time. An exquisite dish of monkfish, chiefly informed by the roasted skin of Jerusalem artichoke, chimed in with the earthy element of 1976 but absolutely underscored the vivid fruit of 1989.

The spirit of Louis Roederer

In these six wines, Lécaillon told the story of a revolution—a revolution in viticulture and a reversal of thinking founded in his own reappraisal of every single detail, his questioning of every received wisdom, and thereby the liberation of his ideas that shaped such exquisite wines—from the vibrant, even joyful 1989, to the supremely elegant 2008; the movingly dramatic 2012, to the timelessly youthful 2013. Right from the ancient genetic material and its careful preservation and propagation, via the chosen sites and the renewal of the soils with enlightened farming, to the intuitive and gentle guiding and guarding of every precious element these grapes bring from earth and sunshine to the winery and eventually into our glass. The ideal that is Cristal has been the impetus for everything Lécaillon achieved; has spurred his enquiry and turned him into the visionary he is. Lécaillon called Cristal Rosé the “Eden gem” of the Roederer estate. “Really, since 1974, this has been our laboratory, where we learn about farming, where we create this feeling of effortless, seamless elegance. Cristal Rosé is our most coveted wine; it has always been the best effort. It is what makes the spirit of Louis Roederer.”

Another treat

As if this stupendous illustration of enquiry and sublimation had not been enough, Lécaillon had another treat in store, embodying that very spirit: 2002 Cristal Rosé Vinothèque. “Vinothèque is a new expression of Cristal Rosé,” Lécaillon said. “It is kept for 11 years sur latte, then a further five years on dynamic sur pointe.” This means the bottles are kept upside down in special racks that allow riddling two to four times a year to lengthen the reductive potential of the lees contained in the bottle neck. Every single detail, every minute step, is questioned by Lécaillon. The enquiry never stops, the future is always right here, with various further vintages of Cristal Rosé already slumbering in the cellars, with densely planted vines slowly extending their roots further and further into the chalky soil of the chosen plots, forging the path for ripe fruit full of flavor that will shine in years to come.

Tasting

Cristal Rosé 2013

(magnum; dosage 7g/l)

Fresh, springy Genoese sponge, fresh lemon, and tart strawberry make the first impression on the nose. More air brings a hint of white pepper on the fruit and a breezy notion of brine that gently expands. The palate is exquisitely crisp, totally taut, completely salty, like a wet oystershell, and utterly mouthwatering. It is astonishingly youthful—as though it was frozen in time—with a palate that is still very tightly coiled. This has not even begun to open and will be an exceptionally long-lived Champagne. One to treasure in anticipation. | 98

Cristal Rosé 2012

(magnum; dosage 7g/l)

A touch of smoke, the inviting aroma of savoiardi biscuits, and a subtle lemon brightness define the nose. The palate has just an edge of smoky caramel, like the slightly caramelized edges of mirabelle in a fruit tart, combined with stiletto freshness. All of this is subtly rich, with a tone of toasted hazelnut woven through that saline, bright body, gently but constantly accentuated by silky mousse. The aromatic quality of 2012 is a gorgeous—distant woodsmoke as smelled at a distance on a snowy day, combined with fruit and such seductive sinuousness. | 97

Cristal Rosé 2008

(magnum; disgorged 2016; dosage 8g/l)

Vibrant pink in the glass. At first, this does not smell that different from 2013—it has that same freshness, that same oceanic breeze, that same citric brightness, with strawberry and redcurrant tartness. But the second nosing reveals chalk. All this is subtle, perfumed, incredibly fresh. The palate is exquisitely tart, super-slender, delicate, and yet so direct, pure, precise, and creamy, with a deeper, subtle savoriness reminiscent of fresh cèpe mushroom and oyster brine. This is an extraordinary wine that is only just starting to come out of its shell. | 99

Cristal Rosé 1995

(magnum; disgorged 2004; dosage 12g/l)

Gold with a copper tinge shimmers in the glass. Wet chalk and fresh, raw, white field mushrooms come with the merest suspicion of honey on the nose. The superbly fine mousse is still buoyant, and while there is less concentration at the core of the wine, it attains a renewed, salty freshness when paired with a creamy scallop and truffle dish. | 94

Cristal Rosé 1989

(magnum; disgorged 1997; dosage 12g/l)

A touch of smoke, a hint of truffle, distant chalk, and, with more air, a sense of singed orange peel and wet stone. A superbly fine mousse pervades a wine that is wonderfully slender but bursting with fruit, with life. This is full-on but elegant, like a joyful genie finally allowed out of the bottle: well cut, striking, smiling, absolutely contoured; trailing creaminess, freshness, and fullness. This comes with absolute energy and is as memorable as it is exquisite, long, and fine. | 97

Cristal Rosé 1976 (magnum; disgorged 1984; dosage 10g/l)

A touch of earth and dried apple that has a slight lift of Parmesan rind and maple syrup. A lot of air brings out a sense of oystershell saltiness and a beautiful lift of hay. The body is slender, the mousse is fine and soft, and the heat of that 1976 summer is still there in the concentration and full-flavored density. It is alive! | 93

Cristal Rosé Vinothèque 2002

(disgorged 2019; dosage 8g/l)

Rosehip tisane and slight smokiness blend in with Genoese sponge smothered in cold whipped cream on the nose. The palate is a return to freshness, to exquisite youth and vigor. This has electric charge and vibrancy, seemingly welling out of its profound, resonant chalkiness, dispersed by the finest, tiniest bubbles. This is so taut, so long, so bright, so insistently present and elegant. Wow. | 99