Nick Ryan reviews The Australian Ark: The Story of Australian Wine by Andrew Caillard MW.

Before anything else, a disclaimer: The impartiality a reviewer requires is beyond me here. The first time I held this work in my hands, tears came. Andrew Caillard has been a mentor to me from my earliest days in wine—occasionally without trying, often without knowing.

Two decades ago, desperate to escape the only office job I ever had, I applied for a position at Langtons, the wine auction house Andrew had co-founded. It wasn’t a particularly exciting job, little more than a store man, but at least it was better than running the copy department of a direct-mail wine club business with colleagues who viewed me as either a drunk or an idiot. Or both.

In applying for the job, I submitted an underwhelming résumé and several issues of a glossy lifestyle magazine that had, in a clear indication of how little it cared for the subject, allowed me space to write about wine. I was summoned for an interview, to be conducted at an inner-city café near the Langtons headquarters. It began thus:

“Right, you should probably know from the outset that you’re not getting this job. Now, how do you have your coffee?”

What I thought was a swifter rejection than even I deserved turned out to be a long, expansive, and career-defining conversation that put me on the path I stumble today. Caillard saw something in my writing that I couldn’t. “I’m not going to let you waste your time in a warehouse. You need to take this writing thing seriously and do more.”

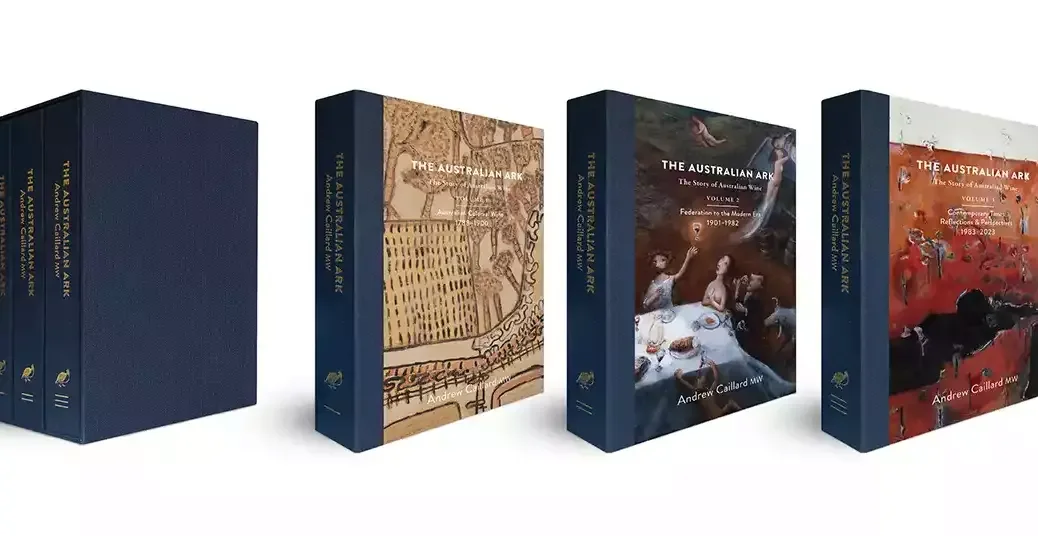

It was not long after this that Caillard began work on the monumental achievement that concerns us here: A two-decade, three-volume, four-kilo (9lb), shelf-straining manifestation of the Caillard exhortation to “take this writing thing seriously and do more.” Andrew Caillard MW not only talks the talk but, in long, purposeful strides, he walks the walk, too. Having been asked initially to produce a pamphlet, only he could produce half a million words that completely reframe the story of how Vitis vinifera took root in an ancient continent.

In 2006, Caillard set out to produce an updated and recalibrated version of Dr Max Lake’s seminal 1966 work The Classic Wines of Australia. That book, written as a predominantly fortified-wine industry was evolving into one focused on dry table wines, needed a glossary and a swollen appendix to pass 100 pages. Caillard had a bigger pool of wines to draw on than Lake, but it was never the plan to expand Lake’s succinct 100-page work by a factor of 18.

As Caillard started to compile his list of the most significant wines ever made in Australia, a bigger idea began to emerge. A few old bottles tell only a fraction of the story. What about the sprawling human story behind them? The story of how the grapevine traveled halfway around the world to a place previously unknown and unknowable. The story of how the vine followed as European settlement spread out across the vast, ancient continent and how that dissemination, and the ambitious dreams of those who sought to practice old traditions in a new land, are a powerful reflection of the big ideas that forged a new nation. The story of how those big ideas from the Old World clashed with those whose connection to this land was even older.

Australia’s (wine) story rewritten

Caillard’s diligent effort to understand where the grapevine sits in Australia’s early colonial history is one of his great achievements here. The Australian Ark: The Story of Australian Wine is set out in three volumes covering three distinct phases of Australia’s wine history.

Volume One, Australian Colonial Wine, covers the period from the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, through to the Federation of the colonies into a unified nation in 1901. This is where some of Caillard’s most important and valuable work appears.

The early European experience in Australia has often been told as a tale of savagery and depravation, most notably in books like Robert Hughes’s The Fatal Shore (1986), and Caillard doesn’t shy away from those elements here. But by viewing some of the major figures in Australia’s history through vine canopies, we see them in a different light.

Captain William Bligh’s command of the HMS Bounty is best known for its mutinous end, but Caillard reveals that the first vines planted in Tasmania were dug in by Bligh’s own hand when the Bounty stopped in at Adventure Bay in August of 1788.

John Macarthur is the most controversial figure of Australia’s early colonial history. Obscenely ambitious, crafty, conniving, and unquestionably brilliant, he has been best known for sheep and sedition. Conventional histories celebrate Macarthur for his leading role in the importation of Marino sheep into New South Wales and the establishment of a fine wool industry that drove the colony’s early fortunes. And they admonish him for his leadership of the Rum Rebellion, Australia’s only coup d’état.

Macarthur was firm in his belief that the world was obliged to bend to his needs, and when the governor of New South Wales, the aforementioned and equally prickly William Bligh, saw it differently, Macarthur marched 400 armed members of New South Wales Corps—the military unit responsible for keeping something approaching order but really more interested in their monopoly over the settlement’s booming booze trade—upon Government House to depose him. History doesn’t record Bligh’s exact words as they barged through his door, but it’s quite likely they were along the lines of, “Oh, bugger, not this again.”

But it is Caillard’s work in revealing Macarthur’s role and, even more significantly, that of his enriched descendants in the importation of grapevine material into the colony and its subsequent dissemination far and wide that adds a fascinating dimension to our understanding of one of the towering figures of Australia’s early history. Caillard puts sprawling Macarthur family estate Camden Park at the heart of the Australian wine story.

Caillard’s first volume rewrites much of the little we knew of wine’s earliest days in Australia and establishes him as a thorough and clear-eyed historian. He reveals the high hopes held by many that an Eden found in the Great Southern Land could become the bounteous vineyard of the Empire, and he recounts how Australia’s first century continued to be shaped by what arrived by boat, whether it was the Silesian Lutherans escaping religious persecution who settled the Barossa Valley in the 1840s or the phylloxera that crippled the promising vineyards around Melbourne in the second half of the 19th century.

Mapping the modern foundations

The second volume, Federation to the Modern Era, charts the years 1901 to 1982 and the boom-and-bust cycles of a wine industry trying to find itself. He details how the newly federated nation had established itself as a winemaker of scale and significance. Between 1925 and 1939, Australia was exporting an average of more than 12 million liters of wines a year to Britain, the value of which exceeded what was shipped in through the same period from France.

How that success crumbled and the industry was left facing some of its bleakest times in the 1940s is a question Caillard tackles with clarity. He details how Australian wine stumbled through that century’s great calamities and tells the story of how it faced another all of its own, when three of the most significant figures in Australian wine—Tom Mayfield Hardy, Sidney Hill-Smith, and Hugo Gramp—where killed in what was, at the time, Australia’s worst-ever air disaster.

He rightly credits the wave of post-World War II immigration from southern Europe with the establishment of a more cosmopolitan wine culture in Australia, and investigates how the establishment of enological studies at South Australia’s Roseworthy Agricultural College set the foundations for a technically proficient generation of winemakers who would take their skills to the world.

He also looks into the careers of the winemakers whose talent and vision laid the foundation for modern Australian wine—giants such as Max Schubert at Penfolds, Colin Preece at Seppelt Great Western, and the legendary Maurice O’Shea at Mount Pleasant—while also giving due credit to unassuming wine scientist Ray Beckwith, who may have done more to elevate Australian wine than anyone (see Andrew Caillard MW, “The Boffin Behind Grange: Dr Ray Beckwith,” WFW 20, pp.168–69).

A unique position and feat

The third volume, Contemporary Times: Reflections and Perspectives, runs parallel to Caillard’s own career, and it’s here that the disciplined distance of the historian makes room for the more complicated perspective of the active participant. That perspective is at the heart of understanding how Andrew Caillard, and he alone, could have produced a work like this.

Andrew Caillard arrived in Australia in late 1982, and embarked on the Wine Marketing course at Roseworthy shortly after. Ten years later, he was a Master of Wine and the winner of the Lily Bollinger Medal, awarded for excellence in tasting, embarking on the fine-wine auctioneer component of a career. He has been a hugely significant figure in Australian wine ever since.

But it is his unique position within Australian wine, the outsider at the very heart of the action, that has given him the clarity this task required. He must have been an oddity on the notoriously raucous Roseworthy campus. The recent English arrival, all public-school polish, whose roots in Australian wine stretch back further than even the scions of old winemaking families with whom he shared classes.

Caillard is always quick to point to his Australian roots on his mother’s side. She was a direct descendant of John Reynell, the man who established the first commercial vineyard and winery in South Australia shortly after his arrival in the nascent colony in 1838. The fact he makes that point in the English accent he’s never lost, even after many years of living in Australia, has always been part of his charm. It’s also what made asking about progress of the book over the past 16 years so much fun—knowing the answer was going to be a beautifully exasperated, “Fuck off!”

Caillard has operated at the very heart of Australian wine for four decades without ever needing to conform to the cliques and cabals that have formed at various points through that time. He has the clear vision of someone untarnished by conflict or self-interest. Where some progressed through patronage, Caillard made his way on universal respect.

Most would have been beaten by the task of producing a work like this, but Caillard delivered—for no other reason than that the country he loved, and those who made wine from it, deserved it. He is quick to point out that he probably wouldn’t have made it to publication without fellow wine writer Dr Angus Hughson coming on board as publishing partner to shepherd the work to physical reality, and the generous and gladly given financial support from some of Australia’s most significant wine figures.

You can see where much of that money has been spent. Licensing for images alone exceeded A$30,000, and the decision to print locally rather than use significantly cheaper options elsewhere was made for no other reason than that it was the right thing to do. It is a truly beautiful tome to hold in your hands, and a rich and nourishing treat for the eyes.

The seed of the project remains, with Caillard’s own list of the Classic Wines of Australia woven through all three volumes in beautifully written and personally informed essays. The Australian Ark also includes several valuable appendices. One records vine importations from 1788 to 2023, listing the arrival of every grape variety and who was responsible for it. Another collects information on Australia’s old vineyards, those planted from around 1842 until 1953 and still in production today. There are also extensive alumni lists produced for each of Australia’s major winemaking schools.

And wrapped around it all is the greatest Australian winemaking story ever told. Its importance for Australia is obvious and can’t be overstated, but to think that it’s only of interest to those within its borders would be very wrong. This is for anyone interested in how wine can reflect every facet of the human experience. This is a wine-writing achievement of monumental importance. Not so much an instant entry into the canon but a canon all of its own.

The Australian Ark: The Story of Australian Wine (three volumes)

Andrew Caillard MW

Australian edition published by Longueville Media & The Vintage Journal; paperback A$199, hardback A$399, linen hardback collector’s edition A$499, leather collector’s edition A$999; US/UK edition published by Académie du Vin Library; hardback US$250/£200, leather collector’s edition £10,000; 1,760 pages; 500,000 words; 1,100 illustrations