With the 2024 Grandi Vini della Contea per la Pace auction in full swing this weekend, Jim Clarke tells the story of the 18th-century vineyard classification of the “princely county” or “Contea” of Gorizia-Gradisca, and its galvanizing relevance for vignerons on either side of the Italy-Slovenia border today.

Forty years ago, historian and journalist Stefano Cosma was conducting research in the library at Villa Russiz, a property well-known to fans of Italian wine, but also an estate of vast importance to the region’s winemaking history. In 1868 Julius Hector Ritter de Zahony gave the estate to his daughter, Elvine, and her new husband, Count Theodor Karl Leopold Anton de la Tour Voivrè, on the occasion of their wedding. De la Tour was of French descent and imported many of the French grape varieties that would eventually “go native” in Friuli and become as much a part of the local landscape as Ribolla Gialla and Malvazia Istriana. But Cosma discovered something even older: a circular dating to March 17, 1787, issued by the Empress-Queen Maria Theresa of Austria, that classified the wines of almost two hundred local villages according to their quality.

The villages stretched across the princely county, or “Contea,” of Gorizia-Gradisca, named for its two most prominent cities at the time, Gorizia and Gradisca. The Empress’s classification is rigorous, or at least extensive, dividing the villages into nine tiers. “Probably the real reason for the wine classification was purely fiscal,” says Gianni Napolitano, Technical Director at local producer Attems. “Where there was a suitable area, there was a good wine that sold at a higher price, and consequently higher taxation. But for today what is important is that the classification dictated a level of quality.”

For a few decades the classification remained an item of historical interest but of little consequence; as often with local history, it took an outsider to appreciate its significance—in this case, another Frenchman. Given his family background, Charles-Louis de Noüe always knew he would end up in wine eventually; his grandmother Jeanne and her brothers Vincent and Joseph-Régis had built Burgundy’s Domaine Leflaive in the 1950s. He married a Roman woman, and after a stint in the U.S. he moved to Italy. A search for great white wine country led him to the Friulian border, and in 2019 he and a local winegrower, Anis Marincič, produced the first vintage of Domaine Vicomte de Noüe-Marincič.

As he got to know the region, Noüe noticed that too many of the region’s best grapes were being undervalued and getting lost in négociant blends. “For me, the idea was to show the value of the terroir and not have that lost in a big blend, and it was easy, because we already knew where the best crus were, because we had the classification.”

The new enterprise focused on Chardonnay, a grape very familiar to both partners, and the results were immediately apparent. “We discovered the different qualities of each cru. The wine called Tejca from Vedrignano is very much like Les Pucelles in Puligny-Montrachet. Groblja, in the same village, is facing east and is much more like Meursault in character, but premier cru, very mineral, very powerful, whereas Bigliana is more like Meursault at the bottom of the slope, full of butter but very well-balanced.” Vedrignano, Groblja, and Bigliana are all second cru on the Maria Theresa classification.

Bringing together the Knights of Contea

While Noüe and Marincič were pleased with the wines, they realized that they needed other producers spreading the same message. They reached out to leading wineries who they knew were sourcing from vineyards in the villages the classification had highlighted, tapping producers like Marjan Simcič, Attems, Villa Russiz, Kristancič, and Klet Brda. Thus was formed the extravagantly named “Association of Knights of the Cru Classification of the Empress-Queen Maria Theresa.” Today there are 30 members, many in the Slovenian wine region of Brda and the Italian DOC Collio—one wine region divided by arbitrary national borders drawn up in 1947. But some members are further afield in Isonzo, Aquileia, and Colli Orientali on the Italian side, and in the Vipava Valley in Slovenia.

Attems is a founding member, with two wines made from Cru sites. Cicinis and Trebes are both second cru, and both feature ponka (or in Slovenian, “opoka”) soils—a distinctive, layered marl and sandstone that Noüe likens to a millefeuille, and which manages water superbly, allowing drainage but retaining moisture further down where the roots can access it. The wines are single varietal, Sauvignon and Ribolla Gialla, respectively, but Attems is planting a third cru site to both Friulano and Malvasia Istriana.

On the Slovenian side of the border Marjan Simcič makes five wines labeled as “cru,” both white and red. The Ronc Zegla Cru is a Sauvignon Vert—aka Friulano, though Simcič favors the French name over both the Italian and the “Jakot” that some producers adopted when the word “tokaj” was denied to them by the European Union. Simcič’s cru wine typically feature older vines, most over 40 years in age; the Ronc Zegla Sauvignon Vert is from 93-year-old vines, believed to be the oldest in Brda.

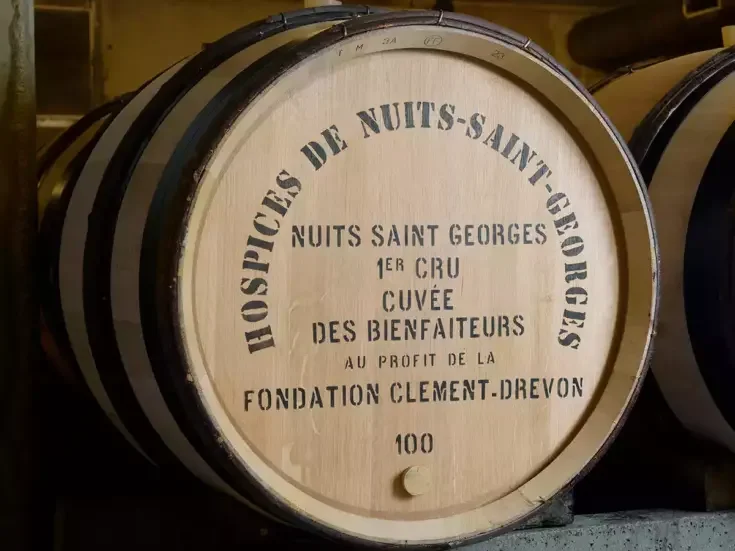

The major activity of the Association is an auction, now in its third year. “The idea was to replicate something we know works well in Burgundy,” Noüe says, “the auction of the Hospices de Beaune: to push the idea of quality, the idea of the crus, and the idea that if Maria-Theresa decided in 1787 that we are in the best place to make wine it was for a reason.”

Contributing producers donate a barrel, which will yield the lucky winner 300 bottles of wine. In 2022 and 2023 each barrel comprised a single lot, but this year bidders will have the opportunity to bid on 12-bottle, 48-bottle, 90-bottle, or 150-bottle lots, or bid to monopolize the entire barrel. While some producers grow other varieties in the cru vineyards—the Attems ‘Cicinis’ is a Sauvignon, for example—auction wines must be single varietal and are confined to Ribolla Gialla, Friulano, Chardonnay, and Malvazia Istriana for whites, and Merlot, Pinot Noir, and Refosco for reds. Vineyard sources must be practicing organic or biodynamic, and maximum yields are 60 hl/ha. Wines are labeled with the name of the cru, the level of the cru, and the varietal, with no mention of the producer. On the Italian side this has led to the wines being declassified, as it does not conform to DOC rules.

The 2024 auction takes place on October 25 and 26; a tasting of the year’s auction wines took place in Vienna on October 15. Due to the low yields in 2022 only 17 barrels are on offer this year; aside from two Third Cru and one Fifth Cru the rest are all First or Second Cru. “‘One’ is like grand cru,” says Noüe, putting the wines into a Burgundian context. “Two is premier cru, Three is village. Four and five are like regional Burgundy, and six to nine, well, they’re still much better than getting a wine from Puglia.”

The beneficiary of the auction is the Monastery of Castagnevizza in Nova Gorica, in particular a set of frescoes in the chapel that were damaged in an earthquake; the first auction raised €62,400 toward the effort. The monastery is a major tourism draw for the area, as well as home to another French connection; France’s last Bourbon king, Charles X, is buried there, having come to Gorizia as an exile after abdicating in 1830.

The title of the auction, Grandi Vini della Contea per la Pace, underlines an even broader message. “This area has been divided by war so many times,” Napolitano says, citing not just the conflicts of the twentieth century but looking back centuries. “It’s very important to embrace the idea of Collio and Brda as one vineyard or wine region across two different countries and cultures, Italian and Slovenian culture, working together, and this is a message of peace”—the “Pace” in the title. “Right now it’s an important message in our region, in Europe, and in the world.”