The chances are that if you have bothered to acquire an opinion (first- or second-hand) of Pinotage as a grape variety, it’s going to be a poor one. But wait—things have changed, and your opinion should keep up.

It’s arguable that one of the worst things that could have happened for Pinotage’s image was Beyers Truter winning the Robert Mondavi Trophy for International Winemaker of the Year at the 1991 International Wine & Spirit Competition, for the Kanonkop Pinotage 1989. Doubtless, many skeptics ignored this as just one of those weird things that happen only too often in wine competitions. (Wrongly, if so: The Kanonkop Pinotage, and especially the Black Label single-old-vineyard version, which emerged later, are fine wines.) But the Pinotage home team took fervent note. In the face of sneers, this was vindication of the national (or at least Afrikaner-national) grape and of treating it grandly.

Unfortunately, few could bring grandeur to Pinotage with the finesse that Kanonkop could—it’s widely reckoned to be a difficult grape with which to work. Given a revived determination that it should be lavished with patriotic ambition, too many wines were overdone, extracted, heavy and jammy, and egregiously tannic—and there was also a lurking problem with bitterness (largely solved by now). Pinotage seemed to need particularly careful viticulture and winemaking to bring out its best, especially when it was being vinified like a serious Bordeaux of the Parker era. It can’t be said that most local Cabernet wasn’t also overdone in the 1990s, but poor old Pinotage took a lot of the flak, and the reputation of the grape was grim, especially internationally.

Many in South Africa were also unenthusiastic, especially since, after the coming of formal democracy in 1994, the old image of the Cape wine industry needed change more than nationalist fervor; the past, it was hoped, was a foreign country, where Pinotage, for many, belonged. André van Rensburg of Vergelegen achieved some notoriety with his declared list of crimes: “Don’t steal, rape, or murder—or make Pinotage.”

Pinotage—the taming of the few

So, Pinotage was largely ignored by the emerging new-wave winemakers. A few progressives did take up the challenge to make a more modern and less sweetly congested wine from the grape. Anthony Hamilton-Russell, for example, with his Southern Right Pinotage from the Hemel-en-Aarde; and Craig Hawkins, now the country’s leading maker of “natural wine,” at Testalonga, made some deliciously light and wonderfully modest Pinotages (one a rosé) for Lammershoek.

Alex Dale, of what is now called Radford Dale, was steeped in Burgundy and perhaps discerned some echoes of Pinot Noir in Pinotage, but when he brought out a fairly light-handed version in 2011, he dodged behind irony and called the wine Frankenstein. In Mary Shelley’s gothic novel, Frankenstein was the scientist who created the monster, not the poor creature himself. People still often get it the wrong way around—though surely fewer since Dr Frank N Furter camped it up in The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The new wine was offered as “a humorous homage” to AI Perold, who had bred the new grape by crossing Pinot and Cinsault (still known here as Hermitage back then). Dale said, “Like the monster, it was born of the laboratory manipulations of a professor, using body parts that should never have been sewn together.”

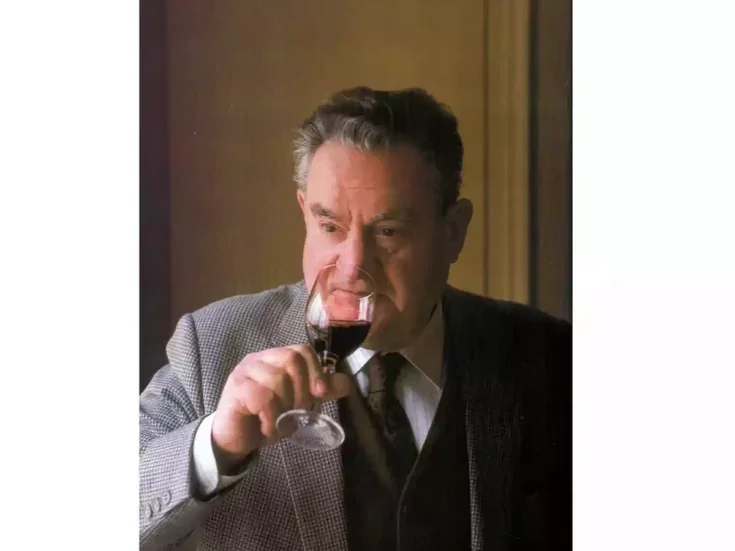

The great viticulturist himself was no monster (apart from some nasty politics, which are now strenuously ignored). Unlike Shelley’s Frankenstein, he remained unhorrified by his creation, and unlike the Transylvanian transsexual Frank N Furter, Perold preferred to cross varieties, not genders.

Many more lighter, fresh Pinotages are made these days, though “bigness” and grandeur remain the goal for most ambitious versions. A couple of factors account for the spread of the new style—and by “lighter,” I mean an alcohol level of 12% to little more than 13% (traditional Pinotages would usually be 14–14.5%) and little or no new oak. First, the “Cape’s new-wave” winemakers have combined their eagerness to evoke local tradition with a confidence that they can take just its best elements. And second, the fashionability of genuinely lighter reds—marked by the local and international success of Cinsault (in the early and mid-20th century, the Cape’s ubiquitous workhorse variety)—has led to similar experiments with other, often inherently superior grape varieties. Earlier-picked Pinotage can show all the perfumed charm and red-fruited freshness of Cinsault, but with a depth and structure that Cinsault only occasionally achieves: positively Burgundian, one or two of them.

There are a few ultra-light, “hipsterish” Pinotages, but for me the real pleasure and satisfaction comes with more substance and vinosity. And there are now starting to be signs that some such wines can happily develop for a decade or more. (Traditional Pinotage, whatever its vices, has the virtue of maturing well for much longer than that.)

Relevant, highly recommendable labels include Bruwer Vintners Liberté, Angus Paul Transient Land, Sun Spider from Giant Periwinkle, Thomas se Dolland from Pella, Nat from Natte Valleij (best known for their very good Cinsaults), Scions of Sinai Féniks (their Atlantikas is too light for my taste), and McFarlane Saturday’s Child. Not forgetting, of course, Radford Dale Frankenstein—a delicious monster. No longer as monstrous.