Wine has long been thought to have medicinal properties, says Stuart Walton, who looks at the ways in which it has been used as a tool of the medical profession and as part of a healthy lifestyle since the 19th century.

Long after the medical profession had ceased to lend credence to humoral theory, wine retained a place in the doctor’s armory.

Throughout the 19th century, alcohol was generally seen as one of the mainstays of a healthy regimen, for all that its action in the body was still only partially understood.

Red wine, in particular, was held to be full of fortifying nutrients and, as such, capable of restoring a sickening organism to the hale and hearty norm.

Good, medicinal wine

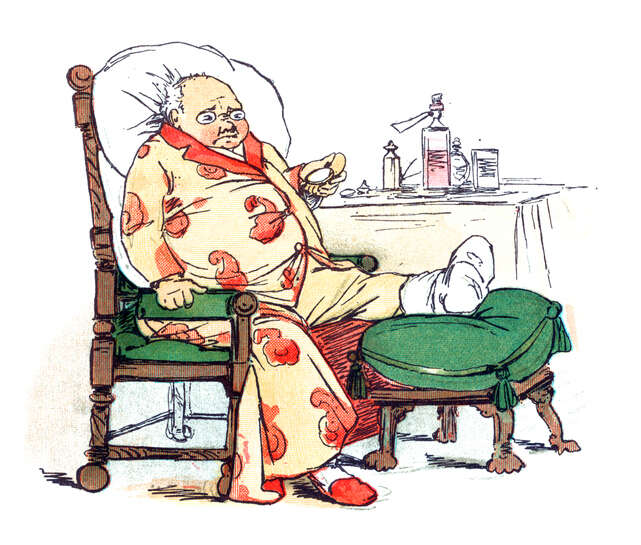

If the laboring classes were sustained by beer, the Victorian bourgeoisie, increasingly prey to the nervous conditions that the infant science of psychiatry would identify and claim to be able to treat, could be returned to a state of robustness with good wine.

At what was considered the medicinal dose, wine was a stimulant, a restorative tonic against withered constitutions and dire exigency.

Moderation was, then as now, the shibboleth that decided whether alcohol taken for health reasons was purely medicinal or purely indulgent, but controlled doses of it were more likely to be therapeutic than not.

Wine played an instrumental part in the life of the Victorian sanatorium, always provided that the individual client had not been entrusted to it as a result of maniacal drinking in the first place. Even then, a glass or two at dinner, precisely because it was subject to a prescribed measure, might remind the inmate of the prudent virtue of self-restraint.

In an address to the British Medical Association in 1905, Dr James Barr stipulated the respective applications of alcoholic drinks to a range of maladies.

A bilious patient who had vomited was to be given Champagne, while decent Port was all but indispensable to those undergoing long convalescence.

Brandy was to be administered in cases of shock, a role it has retained to the present day.

The little barrel around the neck of the St Bernard, popularly believed to contain brandy, was more usefully filled with water to relieve the severe dehydration of those lost among the Alpine peaks, but brandy would certainly have followed it with the arriving medic, restoring circulation to the frozen extremities.

The life of the Alpine sanatorium depicted in Thomas Mann’s great allegorical novel of European disintegration, The Magic Mountain (1924), is a place of civilized retreat, equipped with the very latest in X-ray machines and personal thermometers.

As was typical of such establishments, in one of which Mann himself had spent time before the Great War, the atmosphere was that of an opulent grand hotel, each day building to a ceremonial dinner, copiously supplied from the sanatorium cellars.

On his first evening there, our hero Hans Castorp drinks an unspecified vintage of the St-Julien second growth, Gruaud-Larose.

A festive interlude later in the novel is marked with Mumm Cordon Rouge, while the entire cohort of residents succumbs to a Silenian frolic lubricated with Champagne, Swiss wine, and liqueurs.

Wine, well-being, and wrong

At least part of the assumption that wine and other drink was good for the patient was the mental well-being it delivered.

The medical profession was put on notice from the 1840s, however, by the newly emergent Temperance movement that its recourse to alcohol in the treatment of patients would no longer go unchallenged.

If the Temperance campaigners—who, by and large, advocated not temperance but abstinence—could be dismissed as truculent faddists, organizations such as the British Society for the Study of Inebriety, which published a regular journal of erudite scientific articles on the dangers of what had not yet come to be called alcoholism, was a different matter.

By the turn of the 20th century in the UK, no doctor could afford to overlook the interventions of the Society, many of whose members were themselves doctors.

The same dialectic was in force in the United States, but perhaps because wine, with its supposed health benefits, played a smaller part in the everyday consumption of alcohol, Temperance was always a more militant affair.

What it deplored most of all was liquor—bourbon and rum.

Its vanguard agitators addressed themselves primarily not to doctors but to legislators in Congress, and would not rest until, famously, it resulted in the 18th Amendment, one of the most radical social experiments ever undertaken in a representative democracy.

Even within the provisions of the Volstead Act that paved the way for Prohibition, though, there were exemptions that permitted the use of alcohol as a medical resort.

There were always moments when nothing else would quite suffice. Thomas De Quincey, half-starved and woozy with laudanum in 1820, collapses on a doorstep in London’s Soho Square.

His companion Ann, a 15-year-old prostitute, runs for help and “in less time than could be imagined, returned to me with a glass of Port wine and spices, that acted upon my empty stomach (which at that time would have rejected all solid food) with an instantaneous power of restoration.”