Is it possible to formulate a rigorously scientific test for the theory of terroir, asks Benjamin Lewin MW, as he ponders the ways in which science is used in winemaking.

During the pandemic, when it became impossible to go to tastings, I left wine for a few months to write a book about the conduct of science. On returning to wine, I find that some of my attitudes have changed. When I came into wine from science two decades ago, I was struck by how scientific some aspects of winemaking had become, especially vinification and, to a lesser extent, viticulture. Returning now, I am more conscious of the limitations of the scientific approach.

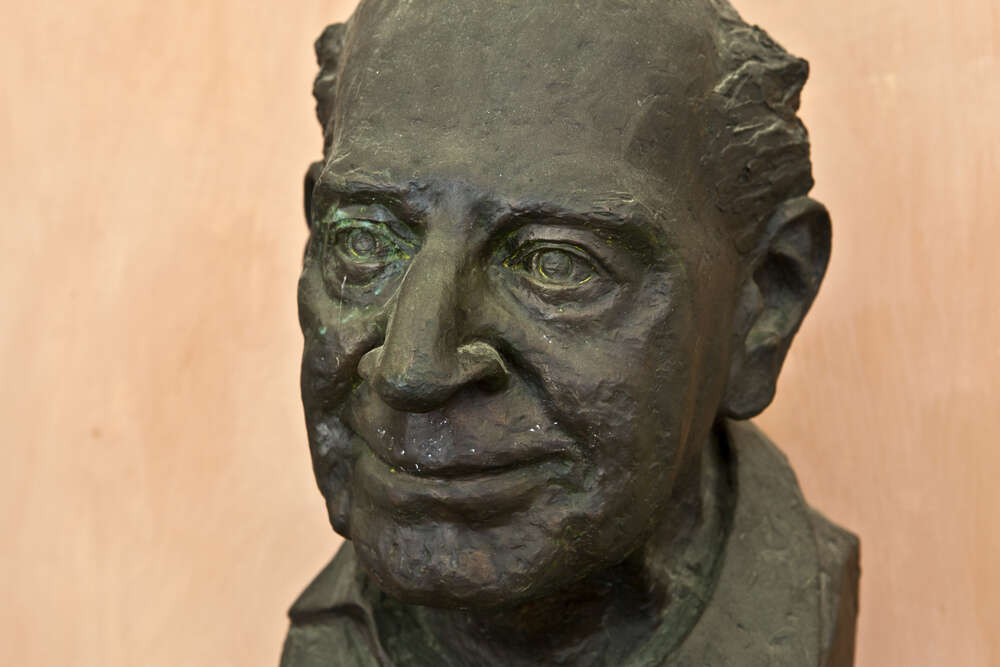

The first thing is to distinguish science from quasi-science. The philosopher Karl Popper developed the view that became dominant in science in the 20th century that a hypothesis is valid only if in principle it can be falsified. Hypotheses that cannot be falsified are dismissed as pseudo-science.

This is quite a strong criterion, since by that measure, pseudo-science nibbles away at the frontiers of science. The idea that life on earth might have originated with seeds sent from a distant galaxy, for example, though authored by a Nobel Prize winner and published in a serious scientific journal, is impossible to test in any way and would therefore qualify as pseudo-science. Some aspects of evolution are a bit questionable in terms of this stiff criterion.

In fact, Popper’s criterion would admit mathematics, as well as physics, chemistry, and (most of) biology, to be science but would deny scientific status to social sciences or psychology. Most aspects of vinification could be treated as scientific by this criterion, but viticulture is more questionable.

The confounding yeast

Vinification does quite well as a science if framed in terms of hypotheses that could be falsified—at least in terms of the chemical processes involved in alcoholic fermentation, malolactic fermentation, or even aging. Whether it makes a difference if the fermentation vessel is concrete, stainless steel, or oak might be regarded (literally) as a hot topic (given the exothermic nature of fermentation) and is swaddled in mystery, but actually, in principle this could be tested by seeing whether any chemical differences are detected after fermentation of the same batch of grapes side by side in different vessels. Many of the processes of aging—especially effects on tannin, acid, and sugar levels—are ill defined but again, in principle, could be tested.

It is less obvious how to test viticulture, though oddly enough, the most dubious practice of all, biodynamics, is the most susceptible to proper scientific testing. There have been inconclusive attempts to test the difference between organic viticulture and full biodynamic viticulture, but I think the real way to test this would be to compare plots that were treated biodynamically but in which one plot gets the homeopathic preparations and the other gets only water. (There may or may not be something in the biodynamic preparations, but I am certain that the notion of “dynamized” water is complete nonsense; that could be tested, too, if anyone had the patience.)

There is the confounding phenomenon that the flavor of wine does not derive exclusively from grapes per se, and possibly not even principally. Wine is not grape juice, and many (or most) of the flavor components are generated as the result of fermentation, either creating, modifying, or magnifying components in the grapes. To some extent, these effects can be determined by the yeast, but if varietal typicity means anything, it must mean that there are differences in the grapes that could in principle be tested for variations caused by the viticultural environment. All the same, any attempt to examine viticulture and vinification on a scientific basis has to allow for the effects of yeast.

Terroir as an act of faith

The holy grail would be a scientific test of terroir. This is tricky because there are so many potential variables. The principle of a scientific test is to hold all variables constant except for the one that is being tested. But how are we to hold variables such as light, heat, wind, and rain constant in order to test for effects? And of course, it’s not necessarily true that the total amount of any variable is the appropriate measure—the extent of heat spikes, for example, could be a more important determinant of vintage character than overall heat during the growing season.

But in any case, these are not the most interesting variables to test. Even skeptics of the influence of terroir would probably concede that light, heat, wind, or water supply will definitely have an effect on the grapes. The sharp end of terroir is surely the effect of the soil, using soil here in the broadest sense to mean not merely bedrock, surface soil, physical properties such as drainage, and chemical properties such as mineral content, but also microbiological life.

(As an aside, is it possible to divorce microbiological life from the grapevine itself? Could different rootstocks be more or less susceptible to different symbiotic fungi? Could the grapevine itself, or at least its rootstock, be part of terroir?)

To determine the effects of soil, we need to exclude environmental effects. It seems doubtful that we could find two plots with soils sufficiently different to be worth testing but that are close enough that the environment is effectively the same. And in any case, it’s really very hard to be sure that the environment is the same. Look at the many cases in Burgundy where plots of land appear to all intents and purposes indistinguishable, but results are reliably different every year, due to tiny (sometimes unknown) environmental effects, such as a slight tunnel for wind.

Extreme measures would be needed to systematize the environment, such as erecting a giant greenhouse. Rain and wind would be eliminated. Heat and light would surely be the same if the plots were reasonably close. The vines would need to be absolutely identical: same rootstock, same scion, same age.

Then the question becomes whether it’s possible to detect differences in the grapes grown in two greenhouses where everything is identical except the soil on which they are placed. But the more interesting question might be whether and how those differences are displayed when the grapes are converted into wine. If you believe that yeast could be part of terroir (though this is really a rather dubious concept), it’s even conceivable that differences could be demonstrated principally after fermentation.

I have gone through this reductio ad absurdum to demonstrate the difficulty of investigating terroir in any truly scientific way. Applying Karl Popper’s criterion, almost all investigations of terroir to date qualify as pseudo-science rather than science, not necessarily because they are ill conceived or badly designed but because the difficulties of controlling so many variables make it impossible to construct a truly falsifiable hypothesis. Terroir must remain an act of faith, not a fact of science.