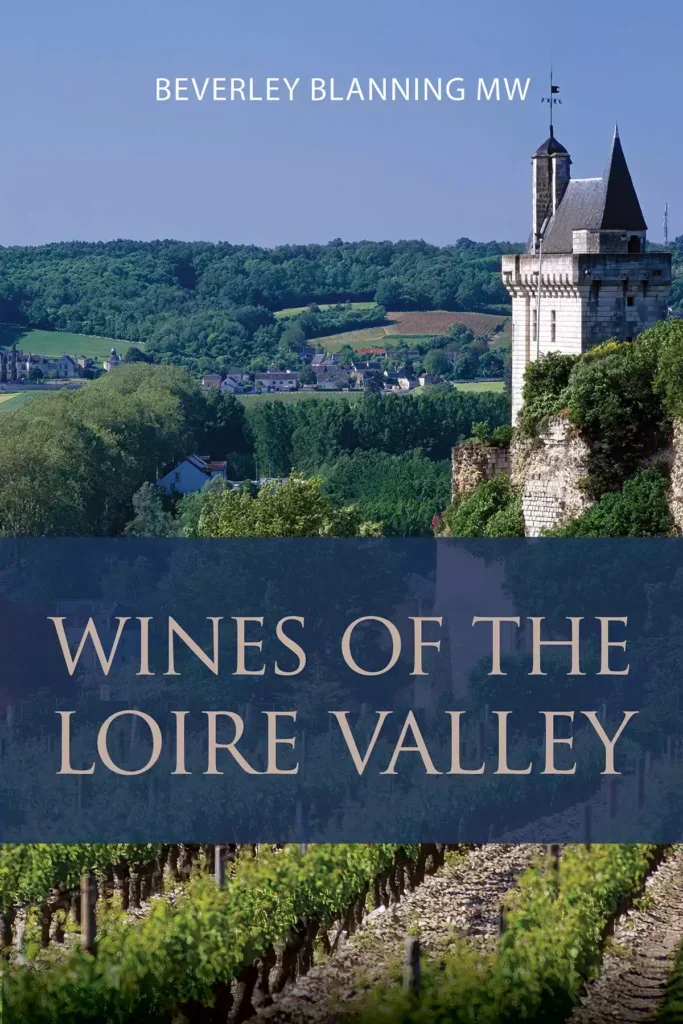

David Schildknecht reviews Wines of the Loire Valley by Beverley Blanning MW.

Jacqueline Friedrich published her lovely Wine and Food Guide to the Loire back in 1998, a planned successor getting only as far as a 2011 volume devoted to “The Kingdom of Sauvignon,” so detailed and tasting note-dependent that full Loire coverage in that format would have run to many rapidly dated volumes. For detail, human interest, historical background, and on-site intelligence, those who already love the Loire have for a quarter century been consulting the vast entries of Chris Kissack’s thewinedoctor.com. But a compact and authoritative, not to mention enticing introduction to the wines of the Loire, has long been needed. Beverley Blanning MW and the Académie du Vin Library have now supplied one.

Not a moment too soon?

If it’s long past time for such a guide to appear, it’s also ideal timing, since, as Blanning writes: “The Loire Valley is enjoying a renaissance in interest that some would argue is [itself] long overdue.” Come to think of it, perhaps it’s lucky this book did not appear significantly sooner. The Loire is undergoing a rapid renaissance in more than just consumer interest. Consider, for instance, 14 formidable estates founded or reborn just between 2018 and 2021 (all but two among some six score profiled in Wines of the Loire Valley). They have emerged from the pandemic crucible flourishing, many finding themselves forced to allocate, a few already approaching cult status.

In Anjou alone, Ivan Massonnat created Domaine Belargus from former Jo Pithon holdings; Vanessa Cherruau revived dormant, hitherto unnoticed Château de Plaisance; Cédric Bourez created Le Clos Galerne; veterans but never-before estate-owners Alice and Antoine Pouponneau established Grange Saint-Sauveur; Domaine Delesvaux passed to Nils and Ombretta Drost; and Terra Vita Vinum emerged from former Domaine Richou. In Saumur, Caroline Meurée and Hervé Maligne established Domaine des Sables Verts and Théo Blet his eponymous estate. In the “Kingdom of Sauvignon,” Antoine Gouffier returned home to purchase ’til-then obscure Domaine du Bouchet, Jean-Philippe Agisson founded Domaine Agisson, Valentin Desloges created Domaine des Quatre Piliers, and a formerly less-than-noteworthy estate became Riandri Viser and Clément Jolivet’s Domaine les Ormousseaux. The Auvergne witnessed the birth of Clos de Breuilly under William Taÿ-Pamart-Ambroise Demonceaux partnership, and then-24-year-old Florent Thinon’s debut. And this is not to mention family-owned establishments that underwent consequential generational hand-offs during the same four-year period.

Coverage at an earlier date might also have missed or insufficiently emphasized important trends affecting the future of appellation contrôlée, such as a now imminent AOC for dry wines from vineyards authorized to produce Coteaux du Layon Chaume, attendant agitation for recognition of dry Anjou “crus,” or the realization dawning on overachieving growers of Saumur-Champigny that the legacy and destiny of their best sites is to excel with Chenin Blanc. These and other important ongoing developments receive adept coverage, augmented by detailed site descriptions and maps. Blanning tracks the increasingly many, often prestigious growers who have abandoned AOC and now bottle their wines as Vins de France, as well as those certified organic or biodynamic (via tiny icons where certification is pending or spurned).

Wines of the Loire Valley: An essential toolbox

Blanning’s guide is slightly unorthodox for its genre in that all three introductory chapters occupy a mere 37 of 352 pages. Historical, geophysical, climatic, and viticultural details—all of which abound—are largely found in the five chapters and 280 pages covering Loire sub-regions and incorporating her estate profiles. Understandably, Blanning notes that her choices there are “personal.” But since she also lists for each sub-region “other producers to try,” it’s fair to question conspicuous omissions. Many of these likely reflect her professed proclivity to go hard on oxidative or bacterially-induced consequences of minimal or no SO2. But snubbing Mark Angeli, Olivier Cousin, Richard Leroy, and the Mosses leaves readers in the dark concerning some of the most talked-about and widely-revered Angevin wine growers, who have profoundly influenced public perceptions of the Loire. Similarly glaring omissions: the Bretons, Stéphane Guion, Sebastian David; and while rightly lauding the late Jacky Blot’s Domaine de la Taille Aux Loups, its Bourgueil sister Domaine de la Butte is inexplicably ignored. From the Coteaux du Loir and Jasnières, only Domaine Bellivière is profiled and one other estate even listed—a shame given the distinctive deliciousness of (no-“e”) Loir wines and the considerable number of estates with international availability yet too little recognition, notably those of perfectionists Sébastien Cornille (Domaine de la Roche Bleue) and Christine de Mianville, but also of Ludovic Gigou (Domaine de la Charrière) and Pascal Janvier. Just three estates in Cheverny are mentioned, none profiled, and while a cool attitude toward “natural” wines would explain the absence of Clos du Tue-Boeuf and Domaine Pierre-Olivier Bonhomme, surely Philippe Tessier is as close as Cheverny comes to a consensus leader.

One gleans a further clue to Blanning’s choices from her having profiled no fewer than ten estates in the Auvergne with especially generous texts and photos. (By comparison, none in either Quincy or Reuilly is profiled.) If reading those evocative Auvergne profiles does not leave readers thirsting to explore the wines as well as countryside of an innovative, neglected corner of La France Viticole, then it’s hard to know what would. And that is surely the point of Blanning’s generosity. Indeed, inspiring thirst for Loire wines generally and an urge to explore them in situ are goals admirably fulfilled by her enthusiastic, insightful, and readily read text, including her many recommendations for places to dine and lodge when visiting. Is there jargon and wine speak? Yes: “Linearity,” “verticality,” “vertical structure,” “vertical acidity,” “mineral acidity,” “mineral fruit” and more. But less than in most writers’ tasting notes. (Even “minerality” was spotted a mere seven times!) On the whole, Blanning’s prose is as clear and refreshing as a youthful Muscadet. If associations of underlying rock types with organoleptic features are no more convincing or consistent than in most books on wine, the making of claims is for the most part wisely left to her profiled winegrowers.

Myriad topics are tackled in side-boxes, most stuffed with useful insights (though an entire page covers breeding of fungus-

resistant crossings, only one of which can claim even limited use in a sole Loire sector). Boxes also succinctly and perspicuously delineate every applicable appellation (including “Dénominations Géographiques Complémentaires”), accompanied by valuable statistics. One two-page “box” is devoted to treatment of a single domaine—Nicolas Joly’s—thereby tactfully managing his omission as a profiled “notable producer.” A rare weakness is the partially box-formatted pages devoted to “natural wine,” which focus almost entirely on SO2, with nothing about yeasts; repeated reference to the risk of oxidation but none to reduction; and a mere two-word mention of filtration. Most terms with which her readers might be unfamiliar, though, are thoroughly yet succinctly covered in a glossary, to which Blanning’s text ought more conspicuously and repeatedly have drawn attention. And readers led by repeated frustration to ignore a book’s index can make an exception here: Blanning’s is a clear, comprehensive model of utility.

Contentious contentions

Wines of the Loire Valley is not without contentions that could be contested or matters that might merit correction in a (well-deserved) subsequent edition. That “[t]here are no significant plantings of Melon anywhere else in the world” would certainly be disputed by increasingly many California and Oregon growers enamored of this grape variety (which for much of the 20th century was quite widely planted in California, albeit deceptively marketed as “Pinot Blanc”). It’s misleadingly averred that at Domaine Didier Dagueneau “all [wines] are … fermented in barriques,” when in fact Dagueneau has long been known both for trademark elongated, proprietary 265-liter “cigar” barrels, and for experimentation with other alternative vessels, such as among the first, if not the first, wooden egg-shaped fermentor. A detailed litany of Jean and Florent Baumard’s “radical new ideas … with little attention paid to convention unless it suited Jean’s ideas” inexcusably omits the Baumards’ long-standing, rancorously contended (and for Quarts de Chaume ultimately outlawed) practice of cryo-extraction. It’s averred that today’s Coulée de Serrant wines reflect “adherence” to “time-honored fashion,” when in fact, they don’t even represent continuity with the wines Nicolas Joly was bottling into the late-1980s, the best of which are still poised, fresh-fruited, and florally effusive—a far cry from the botrytis-induced, high-alcohol, and oxidative overlay that has characterized his wines since the outgoing 20th century.

This volume’s insightful and quote-studded producer profiles often squeeze in descriptions of virtually every wine a proprietor bottles; yet there are a few instances of inexplicable and unfortunate incompleteness. Domaine de la Pepière’s crus are justifiably praised, but neither their Briords nor Gras Moutons bottlings—estate flagships long preceding the advent of crus communaux—gets mentioned. Coverage of Baudry cites only one of that estate’s many estimable, terroir-specific bottlings. Only two of Domaine Pinon’s myriad offerings receive mention (nor does François Pinon’s pioneering of no-till). Domaine Bellivière’s impressively age-worthy Coteaux du Loir Hommage à Louis Derré is overlooked, even as some 150 words are expended on a liquoreux Pinot d’Aunis that this estate has only rendered three times in as many decades. After noting that the wines of Domaine Belargus “are mostly dry,” Blanning fails even to mention that estate’s half-dozen exceptions, three of them Appellation Quarts de Chaume.

Blanning’s strong preference in addressing reds as well as whites is to emphasize vivacity, freshness, and immediate, youthful drinkability, as well as the extent to which today’s growers have themselves increasingly emphasized those virtues, for instance by favoring shorter fermentations with more passive extraction than prevailed in the late-20th century. But this emphasis downplays both the extent to which top practitioners are rendering red wines of depth and concentration that scarcely qualify as “fruit-forward,” and the extent to which youthful drinkability proves compatible with serious aging potential. In addressing “Loire Cabernet Franc: finding its identity,” too little if any room is implied between wines “raw and green” and ones “ripe, fruit-forward and refreshing.”

Volumes in the Classic Wine Library series—revived, revised, and reissued since 2013—have been conspicuously short on production values. Weaknesses have included low-grade paper, poorly executed maps, and grainy black-and-white photos of limited relevance. Wines of the Loire Valley, though, reflects the 2023 acquisition of the series by the Académie du Vin Library—and what a felicitous difference that has made! The extensive maps—some on a detailed scale—are precise, colorful, and maximally informative; the plentiful photos—color as well as black-and-white—sharp, succinctly captioned, and apposite. (Even the evocative front and back covers are captioned.) This book will be a joy as well as a boon to revisit.

Wines of the Loire Valley

Beverley Blanning MW

Published by the Académie du Vin Library; 364 pages; $44.95 / £35