The transformation of top Burgundy into an investment vehicle is all but complete. But there’s hope for savvy drinkers yet, says Roy Richards.

Wine is a drink. There is nothing particularly controversial about that statement, but one might be forgiven for believing that in today’s world it has become a financial instrument. Nowhere is this more glaringly prevalent than in Burgundy, for so long largely and thankfully ignored by an investment sector more at ease with classed-growth claret and Vintage Port. What has changed?

The first explanation is a global phenomenon; the Internet and social media have facilitated access to and information about wines available in such small quantities that the establishment and operation of a market for them was hitherto impossible. The second explanation is more specific, a turning point: With the release of the 2010 Bordeaux vintage into an Asian market flushed with the added value of the previous vintage, the Bordelais made a misjudgment, allowing their greed to overrule their market intelligence. There was no room for growth and profit—indeed, quite the reverse. Disillusioned, that Asian market switched, albeit slowly, to the smaller volumes—and hence rarer wines—of Burgundy with, sadly, catastrophic results for the traditional Burgundy drinker, as is evidenced by current inflationary prices. Over the years, some of the leading estates have tried to deny and inhibit the monetization of their wines, by making gray-market trading more commercially risky for those caught out, naming the primary importer on the label, numbering the bottles, and so on. There was, however, always the feeling that “the lady doth protest too much, methinks,” and that such, usually ineffective, measures amounted only to a tacit collusion with those international market forces, which served to justify price increases at source. The more recent introduction by some less morally ambivalent domaines of non-fungible tokens to accompany their wines on their peregrinations is a belated and honest recognition of the realities of the market.

Should the consumer therefore abandon Burgundy and leave it to the “collectors” and speculators? Absolutely not, because such buyers all seek the same labels from the same estates, so hoping to create a bull market and future profit-taking. Inevitably, this buyer demand leads to price increases. And while it is true that some growers manipulate the market and fuel the fires, the majority are both horrified and embarrassed, aware of the implications of all this for inheritance taxes and tenancy arrangements—but of course nobody can blame the producers for wishing to retain a larger proportion of the profits for themselves. There remain, however, so many estates and less fashionable appellations where quality can still be found at affordable prices. More on this to follow.

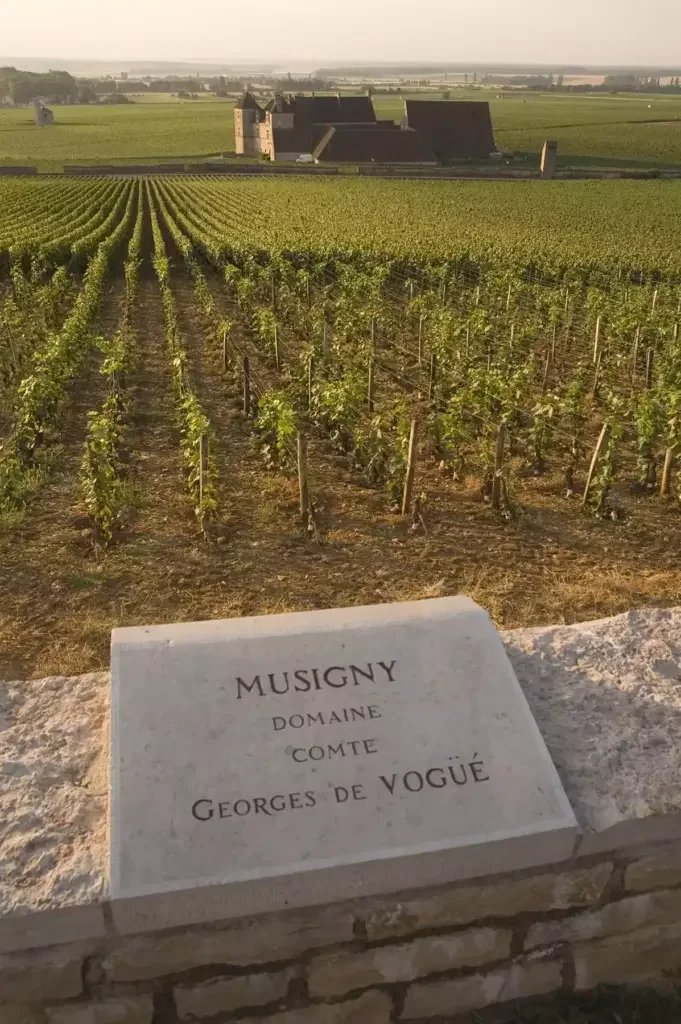

The bottle-price inflation does inevitably cascade into an increase in the value of viticultural land, and indeed vice versa. The relationship is symbiotic, an accelerating upward spiral, as high bottle prices attract vineyard investment, and high vineyard prices require higher bottle prices to render the investment profitable. Not all vineyard purchases are the vanity projects of rich men or corporations. It was not always like this. Henri Jayer, who was of agricultural worker stock, once explained that he was able to buy land in and around Vosne-Romanée after World War II because there was a simple valuation process linked to labor and production; the land was valued by the ouvrée—a historical unit of measure, corresponding to the size of vineyard that a vigneron could work in a day: 4.28 ares (0.1 acre). The consideration for this ouvrée was the current price of a pièce, a barrel (228 liters, or 288 75cl bottles after the elimination of lees) of wine from that same appellation. Comprehensible and logical, so let us apply the principle to the most recent purchase of Musigny Grand Cru. It was only a minuscule parcel, but it is said to have been sold for the equivalent of around €40 million a hectare, or €1,712,000 an ouvrée, which in turn equates to nearly €6,000 a bottle. The math no longer works, and the historical link between labor and land price is broken. Good news for the French taxman; bad news for the independent vigneron.

Burgundy: The undiscovered and undervalued

Many people, understandably, think that each village in Burgundy has its own characteristics, and—broad sweep—that can be true, though geological structure and each individual vigneron’s winemaking signature can count for as much. Let us take an example: Chambolle-Musigny has two grand crus, Musigny and Bonnes Mares, plus a third, unofficial one, premier cru Les Amoureuses. The first and the third of these have stylistic similarities of sensuality and elegance, while the second has little in common with them, being more masculine and brooding in style, demanding age before releasing interest and pleasure. Few know, however, that Vougeot premier cru Les Cras, in another village, is a geological extension of Amoureuses with a similar flavor profile and at a tenth of the price. The Cras, in turn, could never be mistaken for its more august grand cru neighbor, Clos de Vougeot.

St-Aubin is a fascinating and rewarding appellation for white wines with multiple expositions. For some years now, its premiers crus have outperformed many of the lower-lying sites in adjoining Chassagne-Montrachet. Les Meurgers des Dents de Chien overlooks the mighty Montrachet with just some stony scrubland between them. This time the price multiple is closer to 25. The village of Monthelie abuts Volnay and sits above Meursault. Its premier cru Les Champs Fulliots lies alongside Volnay’s Clos des Chênes, which it does not, however, at all resemble. To find comparable finesse in Volnay, it is the Caillerets that spring to mind. And then there is Pernand-Vergelesses, which in the warmer years delivers outstanding quality in both red and white wines; some say that its premier cru Sous Frétille used to find its way into Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru in years gone past. Farther north, in the Côte de Nuits, Marsannay is due to receive much-deserved premier cru status for the best parts of its vineyard. The opulent Clos du Roy and the more mineral Es Chézots comfortably rival their counterparts in neighboring and more affluent Gevrey-Chambertin.

All this wealth of possibility exists without dipping into the Côte Chalonnaise, where Chardonnay from Montagny and Rully produces excellent results—in the right hands. In Pinot Noir, it remains a mystery why few wine writers, still fewer consumers, have discovered Givry, once so famous for its wines—le préféré du roi Henri IV, allegedly because one of his favorite mistresses originated from the village—and now seriously undervalued. In short, cast away your preconceptions; price does not equal quality or drinking pleasure. In the 1950s, the most senior red premier cru of Chassagne-Montrachet, the Morgeot, was sold at the same price as Richebourg Grand Cru; difficult to believe today, but worms have turned and can turn again. The vineyards don’t change—well, perhaps not so true in Chassagne, where much of the Morgeot vineyard has regrettably been replanted with Chardonnay! With a bit of research and an open mind, Burgundy remains within the financial reach of those who like to drink it. For the rest, the value of investments can, of course, go down as well as up. Caveat emptor.

Wine as handbags

This is written not so much in anger—well, perhaps just a little—but rather as a lament for a traditional, family way of life that has remained unchanged since the French Revolution but is now rapidly disappearing; another generation or two, and viticultural Burgundy will be unrecognizable. There is so much that a French government could do to preserve this economy, but there is no political will. They could and should create a level playing field between the family vignerons and the institutional investors. Currently, those families pay inheritance tax every generation, based on values generated by the inflationary prices paid by those investors eager to acquire prime vineyard, le prix du moment, whereas those institutions are immune from such taxes—although an individual shareholder, dependent on his country of tax residence, might well be taxed on his fraction of the whole. Vineyard for these families should be considered an outil de travail, something indispensable to their life’s work, and only taxed when a profit on the sale of that land is actually realized.

Without occupying the fashionable territory of conspiracy theory, it is possible to go further than the lack of political will and to ask whether the gradual elimination of Burgundy’s propriétaire-récoltant is not in fact government policy. In 2008, Jean Méo—a name familiar to enophiles as the founder of Domaine Méo-Camuzet in Vosne-Romanée—published his memoir, Une Fidélité Gaulliste à l’Epreuve du Pouvoir. It makes fascinating reading, for Méo, a brilliant polytechnicien, became a leading civil servant, member of the Gaullist party, and cabinet secretary to General de Gaulle himself. Already in 1958, he notes that the “malaise paysan était très perceptible,” with 23 percent of the population living off the land. “La France,” he concludes, “devait faire sa révolution agricole.” He contrasts France with other countries in the world, noting French niche achievements—Airbus, the TGV, nuclear energy, and luxury goods—while deploring the fact that the sales of Renault cars and vin de pays would always be price-dependent. He even quotes one of his friends, high up in the Treasury department, saying that if France cannot be competitive with cars and agricultural produce, “Bah… nous nous reconvertirons et exporterons plus de robes Dior ou de valises de Vuitton.” In short, the embarrassing peasant class was to be culled and the future economic focus was to be on luxury goods: wine as handbags. Well, that vision has been fulfilled; the policy is succeeding. The grands crus classés of Bordeaux, whose owners are perhaps closer to government circles, cottoned on fast, leaving the Bordeaux and Bordeaux Supérieur way behind and in crisis. Now the same inescapable logic and fate engulfs Burgundy. The independent thinker and drinker will, however, disdain the designer handbags and rejoice in the admirable quality and simple pleasures of the prêt-à-porter, the so-called lesser wines of Burgundy. In an interpretation that Karl Marx perhaps did not intend when appealing to the workers of the world, “You have nothing to lose but your chains.”

Note

This essay was first published in Susan Keevil (ed), On Burgundy: From Maddening to Marvellous in 59 Wine Tales (Académie du Vin Library, 2023; reviewed on pp.50–51 of this issue), and is reprinted here by gracious permission of the author and the publisher.