From Alexander the Great to The Princess Bride, Stuart Walton exhumes some of the many historical and cultural figures who have suffered death by wine.

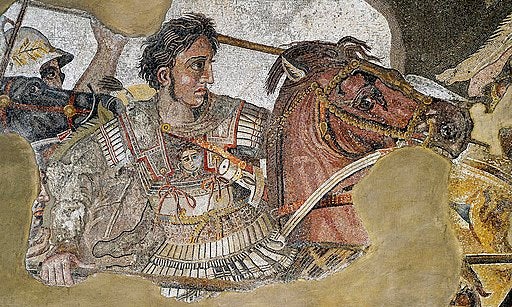

Nobody knows for sure what caused the death in 323 BC of Alexander III of Macedon, known throughout history as Alexander the Great. While on yet another military campaign, and quartered at the palace of Nebuchadnezzar II in Babylon, he took sick following one of his heroic drinking bouts, and began to languish. Eventually too weak to walk, he asked to be carried on a litter across the Euphrates to the gardens on its east bank. His medical attendants soon decided that he was better off indoors, and the litter duly carried him back to the confines of the palace.

In an early version of the frenzies ignited by the spread of fake news, Alexander’s soldiers began to believe they were not being told the truth and that he was already dead. To confound the suspicion, they were allowed to parade through his sick-room, each man seeing for himself the feeble raising of the head and flickering of the eyes that denoted there was life in the young King yet. He died in the early evening of 10 June, still only 32years old, having withered to a decrepit shell over the space of 12 days.

The story has persisted over the centuries that he was murdered, either by a single actor or a convocation of conspirators, through the poisoning of one of the cups of wine that punctuated his days and nights. Revered as a god in human form, Alexander was a heroic drinker, almost certainly alcoholic by today’s clinical definition, given to chugging huge quantities of unmixed wine in defiantly un-Greek fashion. He was famously tutored by Aristotle, whose written work On Drunkenness is sadly lost, but whatever counsel of moderation in the Delphic manner the sage of Stagira might have attempted to instil in the King was quite wasted on him.

Done to death by wine: The poisoned chalice

If he was done to death by wine, it would have been by the emblematic poisoned chalice. Nobody who drank with him on the night he fell ill suffered a similar fate, only him. In a paper published in the medical journal Clinical Toxicology in December 2013, a team led by Dr Leo Schep of the National Poisons Centre of New Zealand speculated that the onset and duration of Alexander’s symptoms pointed to a toxic reaction to Veratrum album, or white hellebore, known in Athenian medicine as a purgative emetic. The alkaloids in a sufficiently concentrated dose of Veratrum, disguised by solution in alcohol, could well have resulted in his horribly protracted demise.

In a fascinating work of what is now known as embodied history, Alexander the Great: The Invisible Enemy (1992), John Maxwell O’Brien gives short shrift to the idea that Alexander was bumped off by poisoned wine. He suggests that the King’s condition might have been triggered by acute alcohol withdrawal, which can have a traumatic systemic impact on excessive drinkers. In the words of the Greek historian Aristobulus of Cassandreia, who accompanied Alexander on many of his campaigns, the King ‘was seized with a raging fever, [and that] when he became very thirsty he drank wine which made him delirious, and that he died’. Did the drinking exacerbate an already etiolated constitution, or was it the direct cause?

At the beginning of the fourth century BC, the most famous poisoned chalice in history was drunk by the father of western philosophy, Socrates, as his preferred alternative to banishment from Athens. The fatal agent in the draught was the pounded leaves of Conium maculatum, or hemlock, which had the status of official Athenian State Poison. It was infused in a cup of wine, perhaps with an extract of the opium poppy too, to ease its passage, although the convulsive effects of Conium involve eruptive vomiting, violent muscular spasms, and respiratory paralysis. None of this trauma is referenced in the peaceful death scene in Plato’s Phaedo, or in the serenely heroic 1787 depiction of the proceedings by Jacques-Louis David, in which the great provocateur is still in full oratorical flow, pontificating forefinger raised, as he reaches for the fatal cup proffered by his acolyte.

The drama of death by wine

The plots of Elizabethan drama and present-day film often turn on the accidental ingestion of an adulterated drink, as when Gertrude inadvertently quaffs the poisoned wine that Claudius had intended for her son, Hamlet. In the battle of wits scene in The Princess Bride (1987), the Sicilian outlaw Vizzini (Wallace Shawn) is induced to drink one of two goblets of wine, knowing that one of them is poisoned, by the Dread Pirate Roberts (Cary Elwes). Since they both drink the respective cups, the trick is either a matter of reverse psychology, or Vizzini has already been poisoned by being persuaded to inhale the odourless toxin before it is added—or not—to the wine.

Undoubtedly the most spectacular death by wine, though, was that of George Plantagenet, first Duke of Clarence, in February 1478. King Edward IV’s younger brother, George was executed in the Tower of London for treason, and the apocryphal story has it that he was allowed to choose his own method of death. He was supposedly drowned head-first in a vat of sweet malmsey, an atrocious waste of Madeira but a recourse that avoided the shedding of royal blood. Although he did not, as some imagine, originate this tale, Shakespeare retails the rumour in Richard III, albeit relating that the drowning took place only after George had been stabbed. When his body was exhumed not long after his execution, though, it was found to be uninjured and intact. Of English history’s many picturesque embellishments, this one might well have been true.