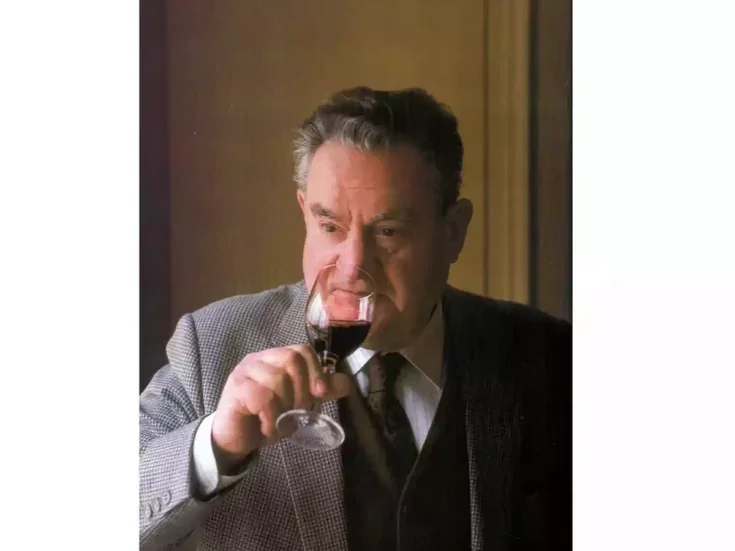

Simon Field MW is greatly impressed by Veuve Clicquot chef de caves Didier Mariotti and the latest vintage of La Grande Dame Rosé.

Madame Barbe-Nicole Clicquot Ponsardin has been variously described as an iconoclast, a strong businesswoman, and a winemaking genius, the shroud of reputation possibly confusing the true and the apocryphal. Such is the destiny of the face (a somewhat austere face, in this instance) of a brand. Whether or not she actually fell upon the process now known as riddling when working at her kitchen table is a matter of idle conjecture. What is more important, and more demonstrably true, is the happy alliance of her love of the Pinot Noir grape variety and the pink-tinged style now known as rosé Champagne, of which 2015 La Grande Dame Rosé is the latest—but far from the least significant—manifestation.

The idea of blending red and white wine, traditionally shunned by the legislature, appealed to Madame in 1818—all the more so since she had identified and nurtured a particular 1.3ha (3.2-acre) plot in Bouzy, Clos Colin, to provide an ideal red wine for the assemblage. Sophisticated geological mapping has proved what Nicole understood intuitively: Namely, that this “hot belt” of soil was and is perfect for still red wine—the Musigny of Champagne, if you like. It turns out that the topsoil—sand and clay, mostly—is three times thicker than elsewhere, the chalk far deeper, and the micro-environment ideally suited to fashion a red wine to be offered up as a blending component. Clicquot’s current chef de cave, Didier Mariotti, an agronomist as well as an enologist, is certainly impressed. He favorably recalls one of Madame’s more gnomic statements—“I taste rosé with my eyes”—which can be interpreted in several ways, provided that one gives synesthetic creativity free rein. Be that as it may, it made more sense to her to blend red and white wine than to infuse white wine with elderberries and black grapes. To us, too.

The 1962 Grande Dame Brut was launched in 1972 to celebrate the house’s bicentenary; its 2015 label marks its 24th outing (see WFW 80, pp.80–81). The rosé has been produced since 1988, shadowing every release of the brut. “La Grande Dame first and foremost,” says Didier; “then, rosé.” Two faces, Janus-like, of the same body politic. The focus is on cerebral elegance and discreet power, more so than with the Vintage cuvée, for which gastronomic pairing is key. This despite the fact that the Vintage generally comprises only 65% Pinot Noir, whereas La Grande Dame has now been realigned to include 90% of the black grape; or perhaps restored, rather than realigned, in the sense that the map had, four decades previously, been temporarily redrawn by chef de cave Jacques Péters (a citizen of Le Mesnil-sur-Oger), who, quite understandably, championed southern Chardonnay. In 2008, Didier’s predecessor Dominique Demarville (now at Champagne Lallier) decided to increase the proportion of Pinot Noir once again—respectful, some may say, of the wishes of Madame Clicquot. “Our black grapes give the finest white wines” is another of her pithy aphorisms.

The 2015 therefore comprises 90% Pinot Noir and 10% Chardonnay, the latter mainly from the grand cru villages of Le Mesnil-sur-Oger and Avize. How does one square this dominance of the powerful variety with the aspiration to create a discreet, intellectual wine? “Well,” says Didier, “we are always pragmatic when it comes to the blending matrix… In 2015, for our Pinot we mainly used the northern villages of Verzy and Verzenay, which make up two thirds of the blend, with the balance from the ‘warmer’ villages of Aÿ, Bouzy, and Ambonnay.” In the cooler 2012, this ratio was inverted. “I am seeking a wine that is fragile, chiseled, and very exact, with stress, vitality, and liveliness at its heart.” Can one really describe La Grande Dame as “fragile”? Well, if anyone is entitled to do so, that person would be the chef de cave; to illustrate the point, Didier asks us to taste the wine in two glasses—one broad and bowl-like, the other closer to the shape of a flute. The first wine sings power and immediacy, for sure, a symphony of backbone and elegance. The flute, however, plays a tune that is more subtle, more discreet, the wine there worthy of the description vin de contemplation. Didier becomes animated as he describes the tasting experience in terms of lying back on a Chesterfield sofa, rejoicing in the sensation of crushed strawberries, soft spice, and pepper. It is hard not to be instantly seduced; and on reflection, a glass or two down, it does indeed appear to make sense that the wine, despite its youth, appears calm, composed, and fundamentally at ease with itself. Quite an achievement per se; rather a feat of marketing, too; quite what one is to make of it will depend, for sure, on personal taste, but the tilt of the rhetoric does not fail to explain what we have in the two glasses before us.

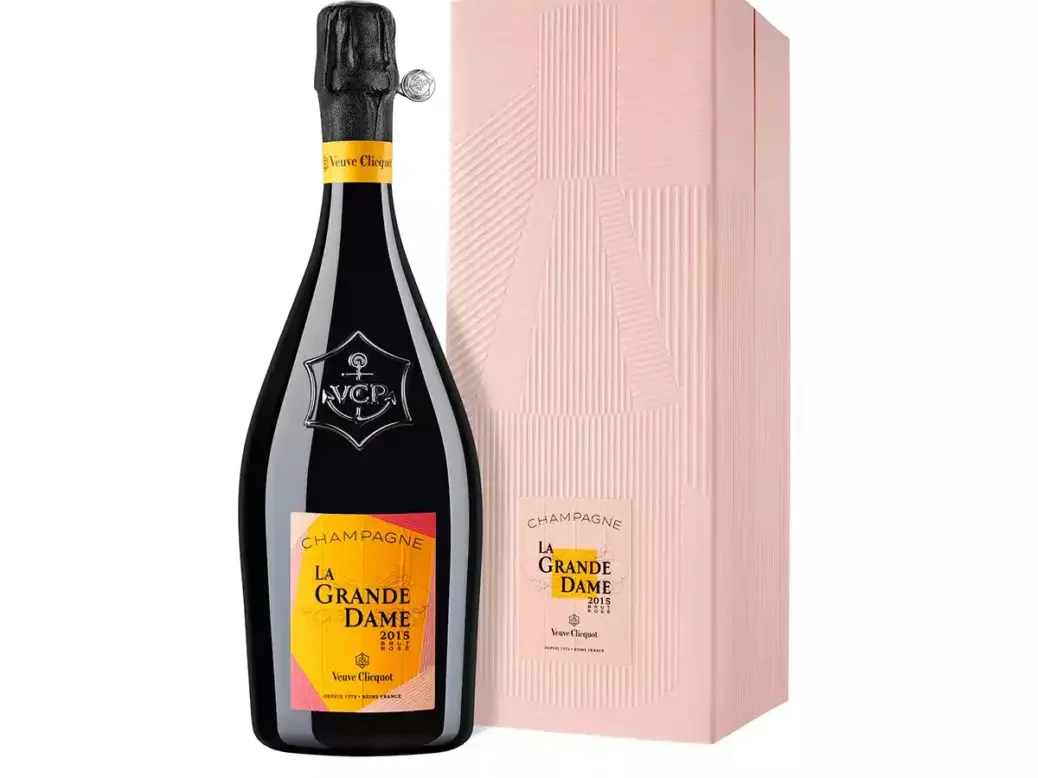

La Grande Dame Rosé: Capturing the spirit

What of 2015? It was a warm year with mid-season drought and a relatively early harvest. Didier compares it to 1976 and, more recently, 2022, rather than, say, 2003, which was also affected by drought; although he notes that the harvest began six days earlier in 2022 than in 2015. In both years, however, picking started in August, with the light of longer, warmer days impacting phenolic structure and latent acidity. Mariotti marvels at how the pH levels have risen (“exponentially,” he says) from 3.05 in 2015, itself an unusually warm season, to 3.50 in all of the past four years, with the exception of the rainy 2021. Thus, for all the talk of excess temperatures in 2015, the numbers point to potential for balance and structural integrity. There are, however, some who have latterly downgraded the reputation of 2015, detecting odd vegetal aromatics and a slightly troubled end to the palate in some of the wines. Not so for the sibling Grandes Dames. “A little noble bitterness on the finish is part of the DNA of this Champagne,” says Didier, and I for one do not find it remotely vegetal. The momentum of meteorological change is undeniable, however, and at some point, the compensating mechanic of earlier harvests and selecting fruit from north-facing villages may not be enough. But that is a debate for another day.

For today, all is fine. I taste the wines over two sessions. First, on their own, with Didier, in his selection of different shaped glasses; then, at dinner in The Pem restaurant near St James’s Park, London, where chef Sally Abé—one of Veuve Clicquot’s key “Garden Gastronomy” partners—has prepared a wonderfully challenging vegetarian menu. “Only Sally and Pierre Gagnaire can make beetroot work with La Grande Dame,” jokes Didier (he might have extended the challenge to the artichoke hearts and the blood-orange jelly). It all works, the wine effortlessly teasing the panoply of flavors on display. It is hard, at the end of the feast, to agree that La Grande Dame is supposed to be less “gastronomic” than Veuve Vintage. Not on this showing. “I want to capture the spirit, the energy, and the verticality that is fundamental to both the brut and the rosé,” Didier tells his fellow diners. His fellow diners are impressed.

“Only one quality: the finest,” said Madame Clicquot, a century and a half before Churchill said something similar about Pol Roger. I think that she would be far from unhappy with her legacy, and not overly perturbed by the fact that Veuve Clicquot is now such a huge brand. Didier, as all his peers, is reluctant to say how much of the production is devoted to La Grande Dame. I joke that my misguided youth was spent as a chartered accountant, and he tells me that La Grande Dame represents less than 2% of Veuve Clicquot’s total production, and that the rosé makes up 20% of this total. He then advises that Clos Colin, which provides all of the red wine added by assemblage (13% in this instance) is a fully cropped 1.3ha vineyard. “I am sure that from this you can work out exactly how much La Grande Dame Rosé is made,” he says, with his broadest Corsican grin. I’m not nearly so sure. I am, however, greatly impressed—by the story, by the winemaker, and by the wine itself. “Optimism through color” is this year’s somewhat cryptic strapline, and Italian ceramicist Paola Paronetto has been charged with designing the gift boxes. We have come a long way from Nicole Ponsardin’s kitchen table… but we can still hear her voice.

Dinner at The Pem, London, March 27, 2024, and with Didier Mariotti, Le Café Royal, March 28, 2024.

2015 Veuve Clicquot La Grande Dame Rosé

(90% Pinot Noir [13% added as red wine], 10% Chardonnay; disgorged July 2023;

dosage 6g/l)

A rich color; copper and worn Keble brick, but not lacking for luster. The nose is serious, savory, and cerebral, discreet in its greeting; there is lavender and black tea behind the crushed wild strawberry; chalk and tilleul, even a hint of tapenade. The pepper is crushed, too, then mandarin, cinnamon, and a shard of cedarwood. Some of the group discern peppermint and Parma violet. The creative impulse is strong, for sure; the allusive charm in no way burdened by the rigor of structure, itself underwriting potential; the firm grip at the back, with Didier’s “noble bitterness,” framing the ensemble without the slightest regret. | 95