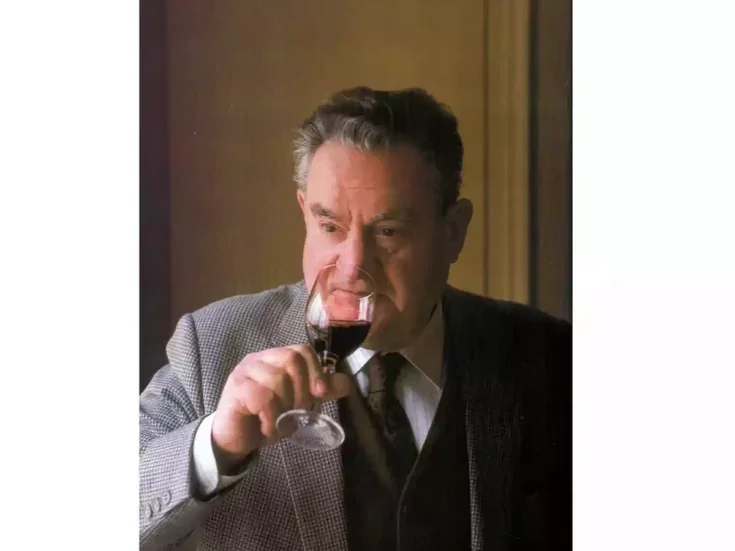

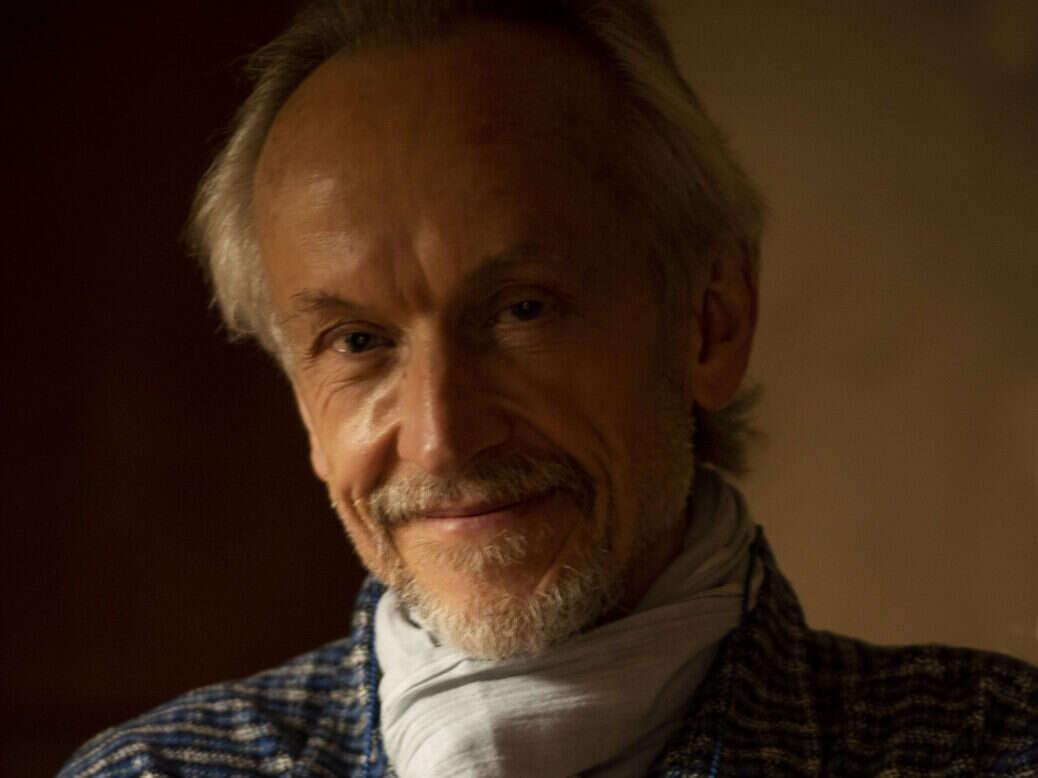

In part one of a candid and wide-ranging interview to mark the publication of his superb new book Drinking with the Valkyries, WFW contributing editor Andrew Jefford looks back over his distinguished career. David Williams puts the questions.

An interview with Andrew Jefford part two: Discovery and astonishment.

Andrew Jefford on Drinking with the Valkyries

David Williams: Why now?

Andrew Jefford: Because the publishers (Académie du Vin Library) were kind enough to show some interest in this long-term project.

DW: The book is a compilation of pieces from across your career. How did you come to make the selection? What was the guiding editorial principle?

AJ: It had to be good stuff—not too ephemeral, not too geeky. Minimum overlap between pieces, fun to read. Almost everything was revised and tightened up in some way or other.

DW: How did you decide on the order?

AJ: I was a bit lost to start with. My excellent editor, Susan Keevil, came up with a helpful initial order, which I then reengineered. We both tweaked a little more.

DW: Did Susan help with the selection?

AJ: I proposed; she disposed. Then in a few cases, I pleaded and she retreated. But I also axed some of her picks. This sounds violent and confrontational, but actually it was a very happy exchange on both sides.

DW: Your career predates the Internet. Did that pose problems? Do you keep all of your old print articles, for example?

AJ: I don’t have all of them—and notably I don’t have my first ever Decanter column, which was called “Autumnal Repose” and drew analogies between Glenn Gould’s two recorded versions of the Goldberg Variations and the craft of winemaking. If any reader can let me have a copy, I’d be grateful. But for this collection, I mainly trawled those of which I have digital copies, dating from the post-floppy-disc era—2005 or so.

DW: Which pieces are you especially proud of?

AJ: That’s rather difficult. Imperfections are everywhere. But I’m happy that we’ve ended up with a book about the experience of drinking wine (and tea) rather than “a wine book”—about wine’s relationship with our past and its cultural value, in other words; about the role that it can play in our lives and the way that it can help us relate to our world and to our fellow human beings; and about the philosophical and emotional lessons it teaches us. Difference, not hierarchy. Astonishment and discovery, not geekdom and mastery. The book also contains a lot of questioning of our usual assumptions about wine. The poetry inherent in wine and in wine drinking is another trope.

Andrew Jefford on a career in wine writing

David Williams: How and why did you come to be a wine writer?

Andrew Jefford: From the moment I first began to drink wine in my early teens, I loved it. I loved the way it turned meals into feasts. I loved how it smelled and tasted, what it did to my brain, and the way that it echoed through culture, geography, and history. I loved its synthesis of the sensual and the intellectual.

So, I began by making wine at home for the family (“country wine” from assorted weird ingredients plus grape-juice concentrate to render it semi-palatable). I bought it when I could (plus wine books); I dreamed about it. Just a hobby back then. After a six-year ramble through university plus a couple of wilderness years, I got a job in publishing as an editor. This lasted four years. Okay, I bought more wine, but those four years were solid gold to me as a writer. I learned far more about how to write well by rescuing the wrecked sentences of C-list celebs who’d been asked to write a book on something or other (cars, dreams, golf, cats—you name it) than I did in six years of reading literary greats at university.

Through a publishing contact, I heard about a book packager looking for a cheap author to write a cheap book on Port, so I volunteered despite being comprehensively unqualified. But I was cheap! After that, I went freelance and combined editing with writing for a while, until the writing took over.

DW: I imagine your first magazine or newspaper byline has a special place in your memory, too. What was the piece, where was it published, and who commissioned it?

AJ: Margaret Rand, whom WFW readers will know for her delicious profiles, was editing a magazine called Wine at the time. She gave the Port book an encouraging review. I contacted her and asked if I could write some articles for the magazine. She said yes—so long as I sorted out all the expenses myself. I’d recently enjoyed the Rosso del Conte of Regaleali, so I contacted the UK importer and asked if they could get me there. They could and they did—and that was the first piece.

I asked the conte if I could take a photograph of him. “Wait there,” he said, and disappeared upstairs. He came back down with a gun and a double bandolier laden with bullets. This impressed me. Sicily was in drought at the time, and the Pope had just interceded with God for rain. As I headed home, it rained. Also impressive. Margaret then let me write “The English Vineyard Year,” a series of 12 articles, one a month, about what was going on at Peter Hall’s Breaky Bottom vineyard in Sussex between autumn 1989 and 1990. After that, it was relatively easy to find work.

DW: You have such a strong authorial voice and such a distinctive world view. Were they there from the beginning? Have you always had the confidence to write as you please, or have you ever had to compromise?

AJ: The first ten years were nothing but tears and compromise. I’d also stress that for the first 20 years I was a print journalist—which means writing to length and then often having to cut and fill afterward, at short notice and some speed. Good subeditors also double as fact-checkers. Your copy gets minced. This, though often humiliating and uncomfortable, is educative—as was my own previous experience as an editor. Many specialist journalists today have only ever written online, for their blogs and then whatever online gigs they end up with. Space, economy, subediting, and revision don’t figure. The results often strike me as rambling and overindulgent. They’d never get past a decent sub.

DW: One of the downsides of being distinctive, of course, is that you stand out more—you’re more exposed. This makes me wonder if you ever come across criticism of your work, your style, your philosophy. And if so, how do you deal with it?

AJ: I’m someone who likes quietness and space to think—so I tend to avoid cliques, crowds, conventional social media, and the gossip mill. I’m also uncomfortable among wine geeks. Indeed, I feel a fake among geeks for my inadequate geekiness. I live in a place where no one knows who I am, and I spend very little time with fellow wine writers (which I regret, actually, because on personal one-to-one terms, I like most of them enormously). I’m also now partly deaf so cannot cope with noisy environments and tend to give surreal answers to questions that I haven’t properly heard, or just smile inanely and say nothing.

All of which is a languid way of saying that I have no idea what people think about what I write. But my guess would be that some consider my writing self-indulgent, pretentious, overburdened, ridiculous, and laboriously “literary.” I also suspect that some of my colleagues consider that I’m tedious, repetitive, ill informed, and wrong about some of the issues to which I have returned repeatedly throughout my career.

They may be right. I sometimes think all of these things myself. When I write anything, I draft it first, lay it aside until I’ve forgotten what I wrote, then come back as a gimlet-eyed editor and often savage and occasionally dump the first draft for failings of the sort I’ve just outlined. But I wanted to enjoy my career as best I could—and doing things the way I did them has given me enjoyment and satisfaction. I also try to write the kind of thing that I’d like to read as a demanding though broad-horizoned editor/reader with a keen interest in wine and a love of language. So, it’s selfish, really.

DW: Selfishly speaking, then, what part of the wine-writing process do you find the most stimulating—the travel, the meeting people, the writing…?

AJ: Writing. But meeting articulate wine farmers is a privilege, as is travel—though global warming and the anthropogenic extinction episode it has unleashed fills me with such horror that I now try to travel only for compelling reasons of livelihood.

DW: How else has your career evolved, in terms of the nuts and bolts of the work, the places (titles) you work for, the things you are asked to do?

AJ: Honestly, I’m pretty much doing what I was doing 30 years ago, except that less of my work is journalism (modestly paid) and more of it is to do with wine education, wine tourism, and wine judging (better paid, and it can double as “paid research” for journalism). I’m now also treated with latitude and indulgence by those good friends commissioning my work, and columns are more remunerative than features in terms of the research/remuneration ratio.

DW: What would you like to do next? What ambitions do you have for your writing? Another book?

AJ: I’d like to write more books. Actually, I only ever wanted to write books. Not having been able to write more books has been the chief frustration of my career.

World of Fine Wine is hosting the World’s Best Wine List Awards on September 12. Sign up for the event here

Read on: An interview with Andrew Jefford part two: Discovery and astonishment.

This article appears in the 18 Nov 2022 issue of the New Statesman, The World of Fine Wine Issue 77