Andrew Caillard MW shares some of the most revelatory findings from his two decades of research into the early history of Australian wine, highlighting the ambitious aspirations of the first generations of colonial producers and the precious vinestock inheritance helping to usher in a second golden age.

Ambitions that Australia could become “the France of the southern hemisphere” seemed fantastical to some observers, but there were early colonial vignerons and administrators who genuinely believed in such a future. Their energy and foresight shaped the fortunes of the Australian colonies. And while wine has never achieved the same level of wealth as wool, coal, and iron ore, it has always been near the center of influence and power.

When Captain Arthur Phillip, a naval officer of German descent, established a convict settlement at Sydney Cove in 1788, it was an abrupt and tragic collision of cultures. The loss of traditional lands, dwindling sources of food, and exposure to European diseases rapidly destroyed aboriginal communities. Inevitably, the history of Australian wine is not divorced from their plight and injustices. Although most early vignerons acquired land grants within the framework of the law, government administrators were not able to control the rampant expansion of grazing lands into the hinterlands of New South Wales.

Throughout the 1800s, the Australian colonies were seen as a potential source of great wealth. At first, there were strict immigration controls. New South Wales was initially a jail, and settlers were convicts, government officials, military personnel, invited essential workers, or gentleman farmers with capital. But the arrival of the steam age, the discovery of gold, and a boom in agriculture and manufacturing attracted more free settlers and new visions. A cottage wine industry developed alongside all the risk, adventure, grim reality, and excitement of 19th-century Australia. But the rampant destruction of European vineyards by the aphid-like pest phylloxera during the 1860s and ’70s led to a massive expansion of colonial wine into export markets, especially Britain and its colonies.

The first golden age of the Australian wine industry—from a trickle in the 1860s, to a boom in the 1890s until World War I—was profoundly linked to the fortunes of the British Empire. After World War I, the Export Bounty Act (1924) promoted fortified-wine production. While it was financially beneficial for the wine industry, Australia’s fine-wine reputation diminished at home and abroad. It would take years to revive. But science and technology, combined with a changing society during the 1940s and ’50s, led to the creation of Max Schubert’s Penfolds Grange Hermitage and the development of pristine white wines. The story of Australian wine during the 20th century mirrors the patterns of social and economic change and development.

From the First Fleet and ports of call

After Lieutenant James Cook’s exploration of Australia’s east coast in 1770, it was known that New South Wales was predominantly influenced by a Mediterranean climate. The provisioning of the settlement at Sydney Cove was calculated. The First Fleet—comprising a frigate, transport, and store ships—was “stored in every part with provisions, implements of agriculture, camp equipage, clothing for the convicts, baggage etc.” Sir Joseph Banks, an influential botanist and friend of King George III, become the de facto minister of New South Wales during the colony’s first years of settlement. He was a gentleman scientist of enormous wealth who had accompanied Cook on his voyage of discovery and circumnavigation of the globe (1768–71). His knowledge of preparing stores for a long sea passage was unequaled, hence Banks was intimately involved with how the First Fleet would be provisioned. The plant material included shrubs, vines, citrus, fruit trees, vegetables, grains, and seeds. Hemp, flax, rhubarb, tobacco, maize, and even acorns were also supplied.

During the 18th century, there were many potential sources of grapevines in England. For instance, the 6th Earl of Coventry’s Croome Park in Worcestershire comprised a vast plant collection, amassed between 1747 and 1809. Among its collection were Black Frontignan, Black Burgundy (Black Cluster), Muscat of Alexandria, Syrian, and Black Hamburgh. The English aristocracy and landed gentry were fascinated by exotic plant material and built arboretums, glasshouses, orangeries, and vineries to house their collections.

Small Black Cluster (Pinot Noir) and Black Cluster (Pinot Meunier) were both common wall-garden varieties, likely to have been brought by the earliest convict fleets. A wine industry had also developed in southern England during the late 1700s. These hardy, versatile grape varieties were grown successfully at Charles Hamilton’s Painshill Vineyard, near Cobham, in Surrey (see James Clarke, “A Most Cursed Hill: Painshill and the Beginnings of English Wine,” WFW 21, pp.80–85).

The First Fleet, which left England in 1787, was provisioned at the start for all eventualities, and it is known that grapevines were brought in from England, including from His Majesty’s Gardens (Kew Gardens) and local nurserymen, in the first years of settlement.

At Cape Town, Captain Arthur Phillip was assisted by the Scottish botanist Francis Masson, one of Sir Joseph Banks’s most successful plant hunters. Almost certainly among the grape varieties collected were Pontac, Steen (Chenin Blanc), Groendruif (Semillon), Hanepoot, and Muscadel, which were all thriving in nearby Cape vineyards, including the convict-farmed Constantia.

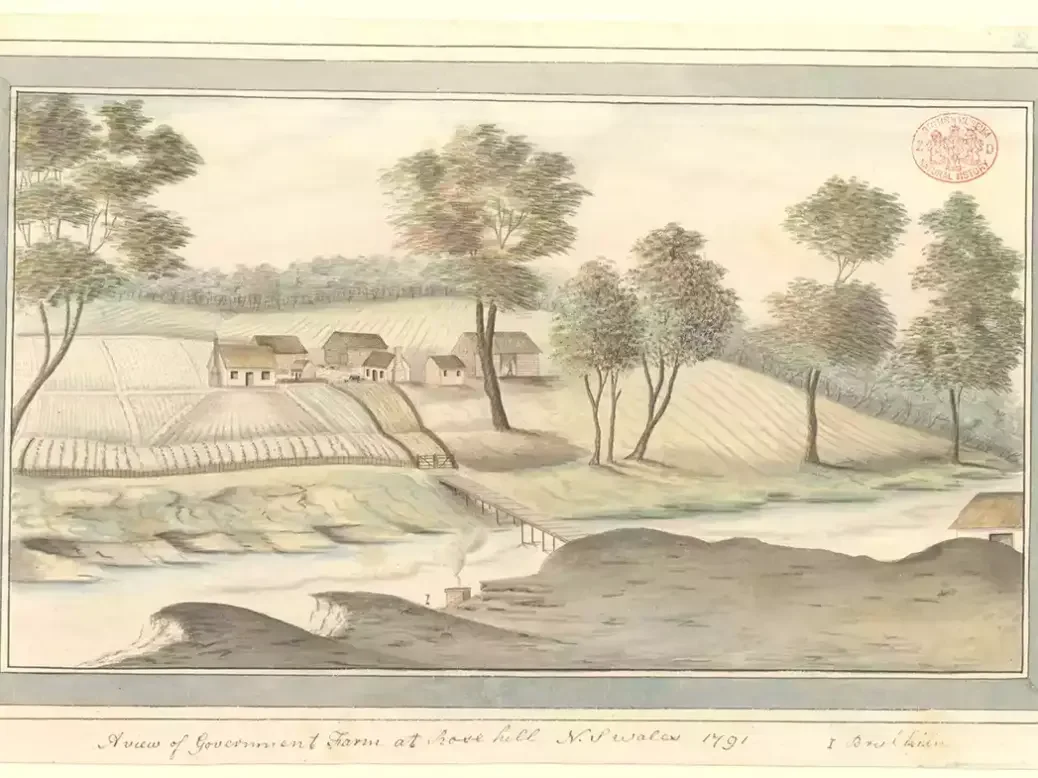

Grapevines were planted at Sydney Cove, near the present-day Botanic Gardens, around the time of the construction of Government House. In late 1788, following an outbreak of blight (anthracnose), Governor Phillip ordered the establishment of a government farm in the more fertile environs of Rose Hill (Parramatta). In addition to fruit trees, vegetables, and various cereal crops, around 2,000 grapevines were planted.

Grapevine cuttings brought into New South Wales during the first decades of settlement were inevitably connected to the ports of call along the route to Australia, including Tenerife, Madeira, Rio de Janeiro, and Cape Town. But early settlers, mostly inexperienced as farmers, also brought seeds and cuttings from England, with mixed success. Verdelho was primarily sourced from Madeira and grew successfully around Sydney from its earliest days. Sweetwater was also a prolific grape variety in early colonial New South Wales. This was later identified as the Sherry grape, or Palomino; Listan Bianco, another name for Palomino, is a stalwart variety of the Canary Islands.

Small vineyards were established inland from Sydney Cove along the Parramatta River and surrounding slopes between 1788 and 1800. This area was originally known as the Eastern Farms (later Ryde). But as more settlers arrived, conflict with the local First Nations population intensified. The New South Wales Corps found itself preventing valuable farmland and crops from being torched.

In May 1791, a one-acre (0.4ha) vineyard was planted at Rose Hill (renamed Parramatta in June 1791) by one of the colony’s first free settlers, Phillip Schaeffer, a German mercenary who arrived in 1790 as a supervisor of convicts but “was accustomed to farming.” Marine Officer Watkin Tench observed 900 flourishing vines just six months later. Captain William Paterson told Sir Joseph Banks in a 1795 letter that Schaeffer had made “ninety Gallons of wine in about two years now.” New evidence, however, suggests Schaeffer could have made the colony’s first wine in 1792.

In 1793, at the young age of 26, Lieutenant John Macarthur, of the New South Wales Corps, was appointed commandant of Parramatta and inspector of public works. This made him a powerful figure in the early days of the colony, because it gave him control over agriculture and the economy. Around the same time, he established a vineyard at Elizabeth Farm at Rose Hill on the banks of the Parramatta River. John Macarthur’s ambitions and zeal had no boundaries. His volatile character regularly got him into trouble, and on two occasions he was sent back to England to account for himself: once because of a duel with his commanding officer William Paterson in 1800, and then because of his involvement in a coup d’état in 1808, also known as the Rum Rebellion.

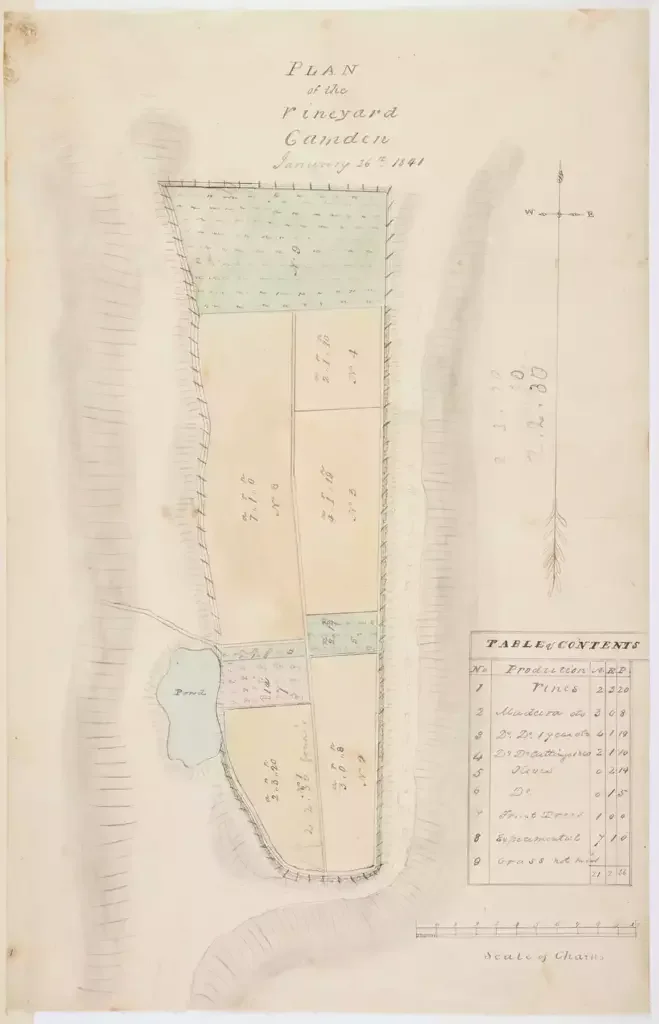

Although Sir Joseph Banks attempted to prevent him from winning patronage from the Colonial Office in London, John Macarthur’s agricultural visions for New South Wales were well received by the government. He was awarded 10,000 acres (4,050ha) of prime Crown land in southwest Sydney. Camden Park, located in the Cowpastures District, would become famous for wool production, viticulture, and wine. On his second and longer stay (nearly ten years in exile) in London, Macarthur’s networking with the aristocracy and political establishment furthered his ambitions. After clearing his name, he was granted permission to return to New South Wales in 1815. Prior to his departure, John Macarthur journeyed to France with his sons James and William (who were schooled in England). Shortly after their arrival in Paris, they witnessed firsthand Napoleon Bonaparte’s triumphal return to the city after his dramatic escape from Elba.

John Macarthur and sons traveled southward to Burgundy and collected grapevine cuttings and other plant material, but as the dangerous political situation intensified, the family slipped over to Switzerland at Vevey, and spent some months there. After the allied victory at Waterloo and the return of peace, they continued their journey through the Rhône Valley and the south of France with an entourage of skilled workers, including vinedressers.

On the family’s return to London, John Macarthur entrusted his collection of cuttings to a nurseryman while a convict ship, installed with a special greenhouse, was being prepared. After arriving back in Sydney in 1817, the vine cuttings were planted out at Camden Park’s newly established plant nursery. Three years later, in 1820, when the vines yielded their first crop, it was realized that most of the vine-stock material shipped was not what they had collected. Most of the varieties were already available in New South Wales.

Between 1788 and 1830, grapevine cuttings available in New South Wales were limited to varieties grown in the Cape Colony, Atlantic islands, or England: Groendruiff (Semillon) Pontac (Teinturier), Muscadelle, Verdelho, Palomino, Black Cluster (Pinot Meunier), Little Black Cluster (Pinot Noir), Black Hamburgh, and Sweetwater.

Sweetwater, which was imported by John Macarthur in 1817, was supposedly sourced from France, but with the collection severely compromised, it may have come from England, where it was widely available. For example, Stillward’s Sweetwater—named for Mr Stillward of the Barley Mow Tavern in Turnham Green, near Chiswick—introduced the variety to England sometime in the early 1800s. Middlesex was the market garden for London, and some of the land at Turnham Green was leased to the Royal Horticultural Society in 1821. But there was possibly a mix-up somewhere, because Sweetwater, now a pseudonym for Chasselas, seems to have had a dual identity at the time.

After experimenting with available varieties, gentleman farmer and explorer Gregory Blaxland at Brush Farm found that Small Black Cluster (Pinot Noir) was the least susceptible to blight. Between 1816 and 1818, he planted a vineyard with this hardy selection and other varieties. He also wrote A Statement on the Progress of the Culture of the Vine (1819), which was the first Australian treatise on wine growing. He accurately described the effect of anthracnose, known at the time as “blight.”

In 1822, Blaxland shipped two barrels of red wine (86 gallons) for evaluation by the Royal Society of the Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. Soon after, he won the very first “international” medal awarded to an Australian wine. The achievement of winning a Silver Ceres Medal in 1823 (most likely for the 1821 vintage) and a Gold Ceres Medal in 1828 (probably for the 1826 vintage) put New South Wales on the map and brought attention to the aspirations of the colony.

High aspirations

By the early 1820s, Australian colonial wine was still something of a novelty. Cape Colony wine was regularly imported, and after 1815, shipping arrived more frequently from France with its regional wines. For example, the brig Jeune Ferdinand’s cargo comprised a “few dozen cases of superior long cork Chateau Margaux, & Haut briant [sic] claret.” In New South Wales, the challenge of blight was also diminishing the harvest and hampering progress. With better equipment and the increasing number of skilled farmers in the colony, new visions for agricultural wealth and a sustainable economy led to the Hunter Valley being opened up to free settlers around 1823. With easy access by coastal shipping, new farms and vineyards began to appear.

The demand for vine cuttings and other plant material created opportunities for colonial nurserymen. Among the most notable was Thomas Shepherd, whose Darling Nursery supplied vines, shrubs, and trees for Sydney’s wealthy landowners. Around 1825, while walking by a front garden in Pyrmont, he discovered a particularly “juicy and richly flavoured grape.” After propagating cuttings, he sent up commercial quantities to Irrawang at Raymond Terrace, Kinross, and other properties. Known by local vignerons as Shepherd’s Riesling, the variety later became known as Hunter Valley Riesling. By the 1940s, it was already known to be Semillon, though it wasn’t until the 1980s that wineries labeled their wines by its true varietal name. The provenance of Hunter Valley Semillon is directly related to Thomas Shepherd’s 1820s cuttings—plant material that must have come in by ship as early as the 1790s.

Ambitious Scotsman James Busby features prominently in Australia’s wine story after arriving in New South Wales in 1824 (see Alex Maltman, “Brisk Wine from Granite but Delicate from Sand: The Geological Legacy of James Busby, WFW 75, pp.104–09). While remembered as the father of the Australian wine industry, he did little to nurture it after leaving Sydney in 1832 to take up the newly created position of First Resident in New Zealand. But his legacy is significant, beginning with the Sydney-published A Treatise on the Culture of the Vine and the Art of Making Wine (1825). It was the colony’s first homegrown wine manual, but a great portion of the text was a translation of Jean-Antoine Chaptal’s L’Art de Faire le Vin (1807, 1819). Busby’s plagiarized work was widely criticized because it was largely unhelpful for growing conditions in New South Wales. But his Manual of Plain Directions for Planting and Cultivating Vineyards and for Making Wine in New South Wales (1830) was better received, also reflecting his more distinguished reputation by this time. Although his career working for government was of mixed success, Busby was active distributing grapevine cuttings to vignerons around New South Wales. Through his association with James and William Macarthur, Charles Frazer of Sydney’s Botanic Gardens, Richard Sadlier at the Male Orphan School, and Gregory Blaxland he was able to source vine-stock material quite easily. It is said that Busby distributed 20,000 cuttings to 50 growers in New South Wales, including George Wyndham at Dalwood and Busby’s brother-in-law William Kelman at Kirkton.

Aspirations for a colonial wine industry that could rival France are supported by the 1824 Camden Park Red Burgundy; advertised in Sydney’s Empire newspaper in March 1857 as a “First Grewth and the most perfect of all known wines.” Nearby, Sir John Jamison’s magnificent Regentville Estate also highlighted huge ambitions. In the meantime, cuttings were sent over to the Swan River Colony in Western Australia in 1829, and these were sourced from Gregory Blaxland, William Macarthur, and Sydney’s Botanic Garden. Grapevines were planted in Western Australia seven years before the foundation of the Province of South Australia.

By 1830, it was believed by many nurserymen and vignerons that New South Wales needed a richer and more diverse resource of vine stock available for settlers. In 1831, James Busby embarked on a four-month tour of France and Spain (before protesting his case in London for better career opportunities in the colonial government). His tour was partly sponsored by James and William Macarthur, whose Camden Nurseries and vineyard southwest of Sydney were already important sources of grapevine and other plant material for the colony.

James Busby collected an extraordinary wealth of grapevine cuttings on his travels, including 437 varieties from France’s Montpellier Botanical Gardens, 133 varieties from the French National Collection at Luxembourg Garden in Paris, and 44 varieties from Syon House near Kew, London. A fourth collection of vine stock, assembled while touring Spain, perished while at sea. If it had arrived intact, many cuttings from this consignment may have flourished in New South Wales and changed the course of history.

Official records indicate that 362 grapevine cuttings arrived in Sydney, alive and healthy. Yet this figure is contested in NSW’s Government Gazette 106, dated March 12, 1834, which reported there were “543 varieties in the whole and only 334 are at present alive,” showing the inaccuracy of the records. The collection was divided into three parts and planted out at Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Busby’s property Kirkton in the Hunter Valley, and Macarthur’s Camden Park.

Busby’s collection was impressive and comprised an extensive list of varieties, including Pinot Noir, Shiraz, Mataro, Grenache, Carignan, Pinot Gris, and Chardonnay. Colonial vignerons were soon able to source a wide range of more suitable varieties, leading eventually to much better wines. But after the evaluation of the Busby material in 1834, William Macarthur and his colleagues, including Thomas Shepherd, believed that the collection was not complete. By the 1830s, German hock and Bordeaux clarets were popular in Britain, but the varieties behind these regional styles were not knowingly available. (Shepherd’s Riesling had not yet been identified as Semillon.) At William Macarthur’s behest, a collection of grape cuttings from Bordeaux was arranged through the négociant company Barton & Guestier. In 1837, Cabernet Sauvignon, Petit Verdot, Malbec, Semillon, and Sauvignon Blanc arrived in New South Wales and were planted at Camden Nurseries for later commercial distribution.

Riesling vine cuttings arrived at Camden Park in 1838, along with a group of German vinedressers who had been recruited by William Macarthur’s brother Edward (a career British Army officer who retired as a lieutenant general) to work at Camden Park. These workers had been previously employed at the famed Marcobrunner vineyard at Erbach in the Rheingau. By the 1840s, Camden Nurseries had become an important source for vine-stock material, especially in South Australia; the Gilbert, Penfold, Reynell, Smith, and Hardy families all bought vine stock from the Macarthurs. Cuttings were also sent down to the Port Phillip District (later Victoria, 1851) and, notably, overland to Yering Station in 1848. Meanwhile, vignerons in the Hunter Valley also distributed grapevine cuttings locally to supplement their incomes.

There were, of course, other importations. In October 1841, a shipment from the Cape Colony comprised 57,200 vine cuttings—20,000 Madeira (Semillon), 5,000 Frontignac, 500 Pontac, 600 Stein (Chenin Blanc), and various others—but it was far too late in the growing season. The consignment was divided up and distributed to subscribers of South Australia’s Vine Association in December 1841, but it appears this importation was not overly successful. It is possible, however, that surviving 1850 plantings of “Madeira” (Semillon) and other genetic material in the Barossa Valley derive from this shipment. Other consignments accompanied settlers, including Mary and Dr Christopher Penfold, on their voyage to South Australia in 1844. On the same ship were Spanish vine cuttings, which may have been destined for William Leigh to plant at his Clarendon property on the eastern side of the Adelaide Hills.

The fortunes of Australian colonial wine improved in local markets as the reputation of Cape Colony wines diminished during the 1830s and ’40s. South African winemakers were reproached by observers as being slovenly in their practices. By the late 1850s, most serious commercial enterprises in the Australian colonies searched for the best vine cuttings available. The Cape was in a similar position, because that colony needed new vine material as well. In 1861, Dr AC Kelly wrote, “The coarse varieties introduced into this colony from the Cape of Good Hope have fortunately been discarded.”

The gold rush and fabulous agricultural wealth made Australia the most exciting place on Earth during the latter half of the 19th century and early 20th century. New methods of mass production allowed winemakers to scale up, with dazzling results. By the early 1860s, Western Australia’s wine industry was also beginning to expand in response to a growing local market and export opportunities. Plantings of classical European varieties were seen as a key to making traditional wine styles. Charles Ferguson, the owner of Houghton’s in the Swan Valley, claimed the vines first planted on his property in the 1860s were sourced from Leschenault and South Australia. A letter by Mr William Burges, a prominent early settler and pastoralist, published by Perth’s Inquirer and Commercial News in 1862, suggests that Cabernet Sauvignon and Malbec were first brought into Perth from Sydney by a “Mr Chauncey.” This is possibly Western Australia’s assistant surveyor Philip Lamothe Snell Chauncy, who resigned his position and moved to Victoria in 1853. The spectacularly successful Houghton clone of Cabernet Sauvignon, widely planted in Margaret River and the Great Southern, is probably related to this pre-phylloxera germplasm.

By the 1860s and ’70s, there was a thriving colonial wine industry, with each jurisdiction enjoying a golden period. This was helped by an influx of settlers, the New South Wales and Victorian gold rushes, and the expansion of settled areas, especially around Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Brisbane, and Perth. It was also a period of rapid growth and industrial empowerment. The steam age—both rail and shipping—had allowed wineries to gear up production, and export markets were opening up. A steady flow of bulk ferruginous red wines, based primarily on Shiraz, Mataro, and Grenache from the Southern Vales, Barossa Valley, and Clare Valley (and later Rutherglen in northeast Victoria), were increasingly being shipped to the UK market, and this would continue for decades.

The formal discovery of phylloxera in 1877 at Fyansford in the Geelong District of Victoria was calamitous at first. It resulted in a scorched-earth policy—a strict implementation of quarantine regulations to mitigate the spread of the dreaded pest. Many important early colonial vineyards were pulled up, and these efforts did slow the progress of phylloxera in Victoria. Meanwhile, South Australia’s quarantine regulations, first introduced in 1875 and subsequently strengthened, have powerfully protected the wine industry. With the largest acreage of 19th- and early 20th-century Vitis vinifera vineyards in the world, there is no other place that has such a profound living connection to the Victorian and Edwardian age.

By the late 1890s, South Australia had overtaken Victoria’s wine production for the first time. While not intentional, the removal of cross-border duties and taxes after Federation in 1901 intensified competition and increased South Australia’s market share in the eastern states. The arrival of phylloxera in Rutherglen in 1899 (the same year as in Rioja, Spain) sharpened agricultural policy, with the Victorian government playing a more active role in overcoming the disaster. The region had become an important source for ferruginous dry red wines, and significant capital investment had followed. But dwindling production and the need to plant on American rootstocks required action. A massive new importation of vine-stock material, collected by Victoria’s state viticulturist Francois de Castella, arrived in 1908. Grape varieties included Mondeuse, Durif (Petite Syrah), Cinsault (also known as Blue Imperial or Oeillade), Tempranillo, Graciano, Malbec, Merlot, Chardonnay, and Sauvignon Blanc. De Castella was instrumental in overseeing the revival of viticulture in northeast Victoria and the return to pre-phylloxera production by the 1920s.

Biosecurity and diversity

Australia’s biosecurity rules are some of the strictest in the world. But periodic imports of grapevine cuttings have been allowed by states to strengthen the library of germplasm in their jurisdictions since the end of World War II. This began in the late 1950s and has continued through the decades. Among the most notable imports were P58 Chardonnay by Penfolds, and Western Australia’s Gingin clone, which arrived in the late 1950s. Since the 1970s, many newer clones from France have been imported into Australia, accompanied by complicated intellectual-property ownership and licensing.

The fabled 1971 Tyrell’s Vat 47 Pinot Chardonnay is quite rightly remembered as a landmark release, but it was not the first varietal bottling of Chardonnay in Australia. The variety’s history in Australia goes back to James Busby’s 1832 importation. Chardonnay was planted out in the Hunter Valley and Sydney environs, including the Kaluna Vineyard at Smithfield (previously the site of the Male Orphan School). During the 1930s, cuttings were sent out by Colin Laraghy to Mudgee, the Hunter Valley, and the irrigation areas. Tyrrell’s HVD Vineyard, which was established in 1908, comprises the oldest-known surviving Chardonnay vines in Australia, and this vine stock may have emanated from Kirkton. Vigneron Brian Croser’s Tiers Vineyard may also comprise genetic material related to this importation. Genome sequencing has indicated that some of his early Chardonnay plantings may have been imported illegally, without his knowledge, into South Australia. The provenance of the Gingin is related to source material from Armstrong Vineyard in California, planted by UC Davis in the 1930s, and investigative work suggests that it was probably related to grapevine cuttings imported into California from France in 1888, from budwood sourced from Meursault.

Kirkton Vineyard was an important source of vine-stock material for new vineyards in the Hunter Valley region throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Although Kirkton was pulled up in 1930, winemaker Maurice O’Shea of Mount Pleasant Vineyard took Pinot Noir cuttings from its 1832 plantings in 1921. They would become the base of many great Mount Pleasant Pinot Hermitage wines in the 1930s and ’40s. During the 1960s, New South Wales’s state viticulturist Graham Gregory took cuttings from Mount Pleasant on behalf of the CSIRO at Merbein in Victoria. After a selection process, the vines were propagated and commercially released in 1974 as MV4, MV5, and MV6. By far the most successful has been MV6, which has performed brilliantly in the eastern states, especially around Melbourne’s Dress Circle of vineyards. The provenance of this vine material is directly related to the cuttings sourced from Monsieur Jules Ouvrard in 1831, a politician and the owner of the entire Clos Vougeot (before its ownership fragmented after 1880), as well as the nearby Romanée-Conti vineyard.

Shiraz has proven to be an amazingly versatile grape variety in Australian conditions. Busby’s 1832 importation, followed by selection of high-performing old vines and breeding in commercial nurseries, is generally accepted as the genetic foundation of most of Australia’s Shiraz vineyards, especially in South Australia and New South Wales. The original cuttings were sourced from a Monsieur Machon, a gentleman of Irish descent who owned a vineyard at Hermitage that was subsequently destroyed by phylloxera in 1887. Shiraz cuttings were also collected by James Busby in the Languedoc-Roussillon, and hence there is gene-pool variation.

Before strict quarantine measures were enforced around 1875, there were other Shiraz importations, including cross-border intercolonial trade. But their provenance is difficult to identify. Victoria’s 1860-planted Shiraz vines at Tahbilk and 1866 plantings at Best’s may come from a different source. During the 1970s, Shiraz cuttings were obtained from Tahbilk by the Nuriootpa Viticultural Research Station, under strict quarantine conditions, for evaluation and selection. The Tahbilk clone, renowned for its concentration and vigor, has performed well in the Barossa Valley and elsewhere since it was released commercially. Shiraz has also adapted brilliantly to Australian conditions, and ongoing selections—including individual vineyard massal selections—have promoted high-quality genetic material and performance. This is exemplified by Prue Henschke’s custodianship of the Hill of Grace and Mount Edelstone Vineyards in the Eden Valley.

Although South Australia can boast the oldest surviving Cabernet Sauvignon vineyards in the world (The Barossa Valley’s 1888 Penfolds Block 42, c.1890s Shliebs Garden, c.1890s Woodlands PF Zimmerman Vineyard, and Langhorne Creek’s 1891 Metala Vineyard), the variety was not widely planted in Australia until the 1960s, despite attempts to introduce Cabernet Sauvignon in the Yarra Valley, the Coonawarra Fruit Colony, and the Swan Valley during the 19th century.

The most prolific Cabernet Sauvignon clones are SA125 and SA126. These were developed during the 1970s and are based on pre-phylloxera vines from Seppelt’s Dorrien Vineyard in the Barossa Valley, which was pulled up during the 1990s. It is believed that this material is related to cuttings sent by Camden Nurseries to Joseph Gilbert at Pewsey Vale in 1847, though it could have been sourced elsewhere, including Reynella. There are distinct similarities in the appearance of both the Reynella and Dorrien clones, with similar clusters and small berries. The Dorrien clone was also exported to Molong in New South Wales during the 1950s and distributed around Mudgee.

Reynell Selection Cabernet Sauvignon, vine stock derived from Carew Reynell’s selections during the early 1900s, probably originate from William Macarthur’s 1837 importation as well. In 1845, John Reynell had ordered vine cuttings from William Macarthur, including “1000 scyras, 1000 carbenet sauvignon, and 1000 malbec ” [sic]. Macarthur believed his Cabernet Sauvignon was “amongst the most valuable of our acquisitions.” While the original vineyards at Reynella have been lost to urbanization, the genetic material survives, especially in McLaren Vale and Coonawarra.

One of the great mysteries of colonial vine-stock sourcing is the origin of Houghton-clone Cabernet Sauvignon. Although the genetic material is referenced as having arrived in Western Australia in 1830 from the Cape Colony, this is highly unlikely. The Houghton clone itself, however, is a selection derived from 1950s plantings at Houghton in the Swan Valley. The vine cuttings were evidently taken from the presently unknown 1930s “Frenchman’s Block,” a vineyard of bush vines that were probably pulled out during economic recession. Between 1968 and 1970, Western Australia’s Department of Agriculture studied the performance of 21 vines, each selected for their yield, health, and fruit flavor. After evaluation, the vines were planted out for further appraisal at Frankland River in 1973. Fifty years later, Houghton clone plantings in Margaret River and Great Southern have become the backbone of these regions’ most famous Cabernet Sauvignon wines.

Australia’s strict quarantine rules, surviving 18th- and early 19th-century vineyards, old-vine legacy, and the development of homegrown selections have preserved the authenticity and shaped the reputations of the country’s regional wines. Clare Valley Riesling, Hunter Valley Semillon, Margaret River Chardonnay, Melbourne Dress Circle Pinot Noir, Barossa Shiraz, Coonawarra Cabernet Sauvignon, and so on are all examples of classic Australian regional styles—and most of these wines are steeped in the story of pre-phylloxera genetic material. The combination of vine-epigenetics, vineyard-management techniques, new technologies, and sustainable practices promises to mitigate the effects of climate change, improve the health of soils and the environment, and drive new outlooks and expectations. A wealth of new vine-stock material from France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Austria, and Germany—together with Australia’s existing heirloom vineyards and superb heritage selections—promises to shape a most exciting and fascinating future.