James Busby has had a lasting influence on wine production in the English-speaking world, notably in Australia and New Zealand, where the itinerant, cantankerous Scot spent much of his life. Alex Maltman returns to Busby’s viticultural writings to evaluate his work on vineyard geology and soils.

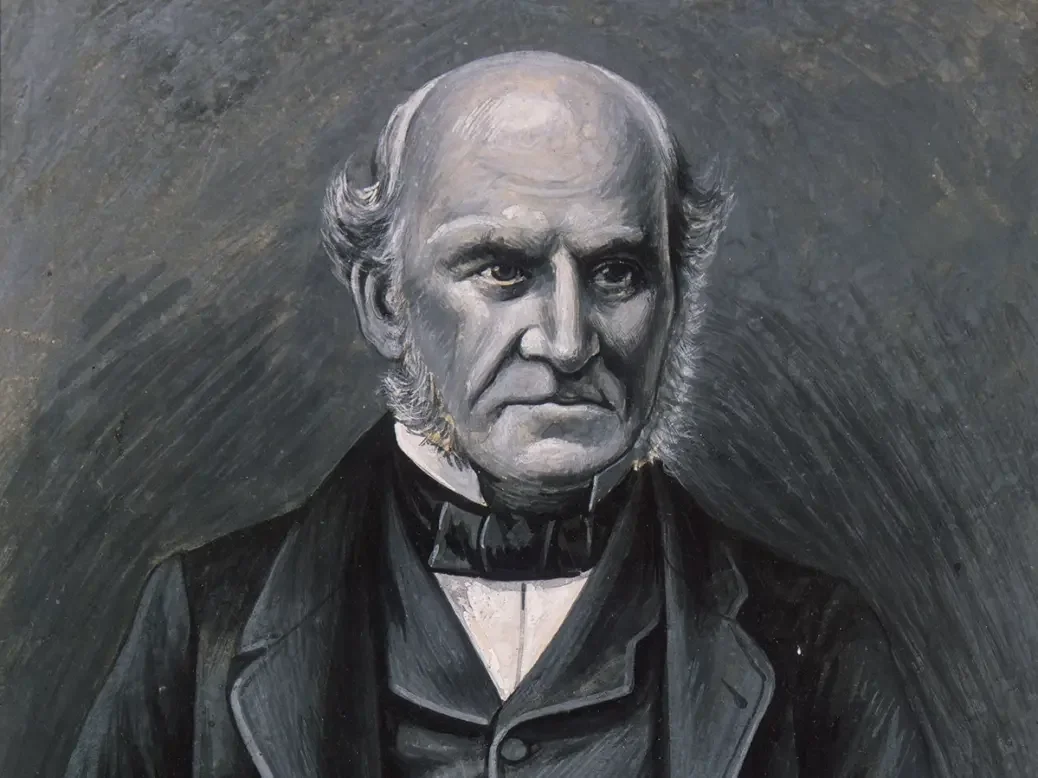

Anerley, a suburb of southeast London, is a modest, unassuming, and unremarkable place. In the district cemetery, however, is the grave of James Busby, an individual who in life had shown anything but those qualities and who achieved rare distinction. In Australia, for example, he had been pivotal in establishing a viable wine industry, and is often said to be its “father.” In New Zealand, he is seen as one of the founders of the country itself, involved with shaping the template that underpins its society today. More widely, he is best known for some of the most influential early writings in English on how to grow vines and make wine.

Busby happened to be staying in Anerley when he died, far from his adopted Antipodean lands, though in some ways the place is fitting. It took its name from the first house to be built in the area, by an expatriate Scot. Anerly is a Scots dialect word meaning “alone,” “solitary,” or “lonely”: Busby was not only himself a Scot by birth, but he led a troubled life in which he never really settled or made friends. Nevertheless, he had far-reaching influence; according to the simple upright gravestone, Busby “drafted the Treaty of Waitangi” and “introduced the vine into Australia.” His epitaph ends, “And their Work Shall Follow them.”

Those first two statements are contestable, but the closing phrase is certainly true, at least of his vineyard manuals. They inspired the infant wine industry in the English-speaking world and beyond, and even today his writings are cited, especially his remarks on vineyard soils. I know of a dozen or so mentions over the past few years, usually in support of the belief that geology can be tasted in the finished wine; a 2018 book on wine terroir devotes almost a whole page to Busby’s words. I, myself, find it curious that things written almost two centuries ago are being used in modern non-historical works; in fact, this is what piqued my own interest in Busby. Much continues to be written about different aspects of this complex man, but I’m not aware of any evaluation of what he wrote about vineyard geology and soils. That is the focus of this article.

James Busby: The formative years

James Busby was born in Scotland, within sight of Edinburgh Castle. His father was a jobbing ground engineer, born in northeast England but then assisting with developments in and around Edinburgh. (One of them was at the city’s Royal Botanic Gardens: Little would he know that today, around two centuries later, in the equivalent Royal Botanic Garden in Sydney, there would be a café called Busby’s Bar.)

Busby drifted somewhat as a youth, doing a bit of farming in Ireland, dropping out of university after one year, even working as a haberdasher. Through helping his father, he became interested in horticulture and then in what we would today call agricultural economics. Which crops were most profitable to grow, in a particular climate? Aged just 17, he had the confidence to pursue the question by visiting France, renting a cottage in Cadillac, across the Garonne from Sauternes. There he became convinced that wine grapes are, given a suitable climate, one of the most valuable cash crops. And from observing some of the vineyards and devouring the current French viticultural writings—especially the magisterial publications of the great Jean-Antoine Chaptal—Busby began to form his own views on viticulture.

In 1823, the Busby family emigrated to Australia, Busby senior having been promised an appointment to deal with mineral and water matters in the growing colony. During the Busbys’ long sea journey (accompanied by two milking cows, sheep, pigs, chickens, and, intriguingly, cases of wine), young Busby began to write his first major work: A Treatise on the Culture of the Vine, and the Art of Making Wine. Along with sundry other things he had written during the journey, it was published in Sydney just a year after his arrival. Busby also brought with him vine cuttings that he had collected en route during a stopover at the Cape of Good Hope.

But Busby’s arrival in the new colony was hardly messianic. Vines had been imported before, and there had been earlier writings in English on the possibilities of Australian viticulture; moreover, some settlers disliked the pompous tone of the new arrival’s pronouncements. It probably didn’t help that the expensive and verbose Treatise was, in Busby’s own words, meant for “the higher classes.” Then as now, Australians didn’t like ostentation. One Sydney critic wrote that the instructions were “like putting a sum in compound interest before a child who had never learnt the multiplication table.” Moreover, the vines he had brought soon perished. And it seems that Busby’s prickly and arrogant nature—traits that were to dog his whole life—soon began to show.

No sooner had Busby contrived a position teaching agriculture at the Male Orphans School near Sydney than he was making enemies and was sacked. Busby proceeded to challenge this perceived injustice, the start of a preoccupation that was to last the rest of his life. Now unemployed, Busby was driven to try his hand at trading cutlery, and the 1828 Sydney census reports his employment as “tax collector.” To the ambitious young Busby, this was ignominy. He resolved to return to Britain and appeal his job dismissal from the school in person at the Colonial Office, as well as to scheme for an official appointment of proper status. This decision had two important consequences for the story here. First, the land that his family had acquired in Australia was developed as a vineyard in his absence; and second, it allowed him to pay a second visit to France.

Kirkton, the “Busby vineyard”

Because the Busby family were free settlers (as distinct from convicts) with more than £500 to their name, they were entitled to a grant of land. The allotted Busby plot was in the Hunter Valley, north of Sydney. Today, this is a playground of weekending city dwellers enjoying the resorts, festivals, wineries producing renowned Semillon wines, and so on, but in the 1820s it was largely dense brush forest with only one overland road. Consequently, land close to the river was much the most desirable because of the access by water; and for most settlers, the flat, alluvial soils offered fertility and relative ease of working for agriculture.

But Busby junior was interested in planting vines, so what would he have thought about the site? His Treatise emphasized the overriding importance, for vine growth, of factors to do with climate—the Hunter Valley was certainly more suitable than Sydney—and that the main thing about the soil is the need for it to be poorly fertile, loose, and free-draining. So, Busby must have realized that the alluvial soils close to the Hunter River were less than ideal. (It is notable that of the half-dozen or so vineyards that were planted there in the first half of the 19th century, only one now remains: George Wyndham’s plantings at Dalwood. All today’s Hunter wineries are elsewhere in the valley, on various soils, such as limestone and basalt.)

Nevertheless, the Busbys directed their allotted convicts to build a residence on the land. Father John was busy in Sydney, so when James decided to go back to Britain temporarily, his brother-in-law William Kelman took over management of the land. And so it was that Kelman, rather than Busby, established a vineyard there, and it was he who gave the property a name. Before Kelman had emigrated from Scotland—on the same ship as the Busbys—the young lad had played on the estate for which his father was the bailiff, a place called Kirkton on the outskirts of Fraserburgh in the northeast of the country. This was to be the name. Sadly, rather like Busby himself, this new Kirkton was to have a troubled history.

Busby on soils

What does James Busby’s Treatise say about vineyard soils? Noticeably, he says little about geology in the sense of the underlying bedrock. He does, however, explain in some detail how pebbly, calcareous, volcanic, and granitic soils all usually have the appropriate physical properties for viticulture. Clay, however, is to be avoided. Clay soils (Busby actually uses the technical term argillaceous) tend to be cold, he explains, with their coherence inhibiting warmth from reaching the vine roots, just as with rainfall. Similarly, their firmness prevents “the dissemination of the minute fibres of the roots.”

Some of his remarks are awry—the best Bordeaux vineyards are not on soils with decomposed granite; volcanic soils are not impregnated with fire—but most of his statements are carefully justified. His conclusion summarizes his position: “The intrinsic nature of the soil is of less importance than that it should be porous, free and light.” All this is closely argued and wholly in line with other writings of the time—indeed, with today’s scientific views.

But then Busby unleashes a single sentence completely out of the blue and at odds with all that has gone before. In its own single paragraph, Busby declares ex cathedra, “The sandy soil will, in general, produce a delicate wine, the calcareous soil a spirituous wine, the decomposed granite a brisk wine.”

He offers no expansion, no explanation of how any of this might come about. Presumably the ideas are based on anecdote, perhaps on things he heard while in France; the baldness of the statement certainly contrasts with the reasoned approach of the surrounding text. Take, for example, calcareous soils—that is, limy, containing significant calcium carbonate. In an earlier passage, Busby had explained how such soils are beneficial for vine growth by promoting free water circulation, allowing “numerous tender ramifications” of the root system, and so on but made no mention there of any effect on the wine itself.

But now he asserts that they yield a “spirituous wine.” By this, Busby clearly means high in alcohol, because in his section on climate he remarks that warmth promotes “the production of saccharine matter and generally strong spirituous wines, sugar being necessary to the formation of alcohol.” For his discussion of calcareous soils, he had used the example of the Champagne region; he must have known that those soils didn’t lead to high alcohol. In any case, how might calcareous soils promote a higher alcohol content? Busby just doesn’t say.

It is this single sentence that is commonly the basis for Busby’s works being cited nowadays, usually to bolster claims about the importance of soil for the taste of a wine. For instance, in a 1977 conference paper, Italian viticulturist Mario Fregoni stated ways in which soils influence wine flavor, and they are taken almost verbatim from Busby: Sandy soils give light, aromatic wines; calcareous soils give high alcohol, and so on. In turn, Fregoni’s list is much cited by subsequent authors. To my knowledge, however, none of these later authors offers, just as Busby did not offer, anything about the rationale of the claims or their validity. And we should remember that the lengthy Treatise was based solely on a single visit to parts of Bordeaux and Busby’s reading of the current French works—seemingly another mark of his self-confidence (conceit?).

Before Busby left Australia for London, he found time to rewrite his Treatise with a more approachable and practical tone. The change is reflected in the new title: A Manual of Plain Directions for Planting and Cultivating Vineyards, and Making Wine in New South Wales, and this version was aimed fair and square at “the class of smaller settlers.” In it, Busby again asserts that the main attribute of vineyard soils is their being “loose and open”; he mentions that usually calcareous, volcanic, and granite soils are very appropriate but that stiff clays or rich alluvium loam are unsuitable. There are, however, two differences from the earlier version regarding soil.

First, he states that “many people in the wine countries” believe that the nature of the deep subsoil has a role, both in vine growth and the wine itself. In the Treatise, Busby had barely mentioned what might lie below the topsoil. In the new Manual, he does, but then goes on to reject the idea. “While the truth of this can scarcely be considered as established, I question whether, were it ever so well ascertained, we could derive much advantage from the knowledge of it.” In other words, despite introducing it, he saw little relevance in the bedrock geology. And second, that oft-quoted cryptic single sentence about wine traits varying with certain soil? In this new version, it’s absent.

A return visit to France

During Busby’s return to Britain, he took the opportunity for a four-month tour observing agriculture in France and Spain. Among numerous other things, he visited selected vineyards and carefully amassed vine cuttings. Eventually, Busby was to ship to Sydney’s infant Botanic Garden a large collection of carefully cataloged vines, where they were propagated for Australian viticulturists to use. Sadly, these cuttings again did not fare well in the garden—in fact, today, Busby’s Bar is the only visible reminder of his connection there.

Before their demise, however, duplicates of the cuttings found their way not only to the vineyard at Kirkton but to numerous other sites in the Hunter Valley and elsewhere in the state. They also went, for example, to the Clare Valley, Adelaide Hills, and McLaren Vale in South Australia, and to Geelong, Ballarat, and Bendigo in Victoria. They were acquired by Dr Penfold for his “Chardonnay,” and by Samuel Smith at the new South Australia estate he was calling “Yealumba” (sic).

Without doubt, this collection of vines was Busby’s major contribution to Australian viticulture, though discussions on its value continue to this day. For instance, the focus on French and Spanish cultivars meant that grapes from elsewhere were long neglected in Australia, such as the Italian varieties that are now proving popular.

The outcome of Busby’s sojourn in Europe that is of more relevance here is the diary of his visit, with his updated views on vineyard soils. Published in 1833, it is titled Journal of a Tour through Some of the Vineyards of Spain and France, though in fact it covers a whole range of farming matters—from hedging and garlic, to sugar cane and silkworms. Regarding vineyard geology, his views have radically changed in two ways. First, he has become convinced of the supremacy of calcareous soils for producing quality dry wines; and second, he now stresses the defining importance of methodology: how the vines are raised and how the wine is made.

Soil volte-face: it must be calcareous

Busby was first struck by the significance of calcareous soils in Jerez. He noted that the sandy soils called arenas led to inferior wines, while the finest came from the calcareous albariza soils. Later, he visited Burgundy and, on the basis of several localities around Gevrey and Vougeot, declared that the calcareous higher vineyards of the Côte d’Or yield “the dryest and best wine.” The clay content increases downslope, and so the wine “falls off in quality till it becomes the vin ordinaire of the country.” In Champagne, he was again struck by the desirability of calcareous soils, though he conceded that the clayey soil around Aÿ “affects the quality of the wine, but not in a great degree.”

However, the place of Busby’s seeming epiphany is a surprising one: the famously granitic Hermitage hill in the northern Rhône. There, Busby made an unplanned call on a local proprietor who told him that the finest Hermitage wine came from a blend of grapes from the “ordinary granitic soil” with those from “a belt of calcareous soil” that crosses the hill. Busby obtained some of this latter soil, and after seeing it fizz when he poured vinegar on it, he wrote that indeed it contained “a considerable portion of lime.” He then proclaims, once again without expansion, that “it is probably to this peculiarity that the wine of Hermitage owes its superiority.”

In asserting this supremacy of calcareous soil, Busby is completely reversing his earlier conclusions, stated in both the Treatise and the Manual. Moreover, he is rejecting outright the view of Chaptal and the other eminent French writers of the time. They consider, Busby reports, that “provided the soil is porous, free, and light, its component parts are of little consequence.” “Granitic, schistose, argillaceous, flinty, sandy, and calcareous soils” are all “equally well qualified to produce […] wines of the finest quality.” This was exactly Busby’s previous position; now he is dismissive.

Writers on other aspects of Busby’s life have commented on the man’s perpetual arrogance and pig-headedness—and that again seems to be illustrated here. He declares that Chaptal and company have been deceived. Jean-Antoine Chaptal, Comte de Chanteloup et Comte de l’Empire, once Napoleon’s minister of the interior, was France’s preeminent expert on chemistry and agriculture, including viticulture (he owned a vineyard in the Loire), and author of several standard textbooks. Busby had no training and virtually no hands-on experience of either viticulture or geology.

Nevertheless, apparently because of a chance conversation during his short visit to Hermitage, Busby pronounces, “These writers have in many instances been misled by the representations which had been transmitted to them. When Chaptal and Cavoleau cite the wine of Hermitage as an instance of the excellence of wines produced upon the debris of granite, the fact is that the wine of the hill of Hermitage owes its superiority over the wines of the other hills in its neighbourhood only to the circumstance of the granitic soil of a part of that hill being mixed with calcareous matter; and but for this circumstance, I am satisfied that the wine of Hermitage would never have been heard of beyond the neighbourhood where it grows.”

Busby had probably visited Le Méal, the vineyard high on the southern flank of the Hermitage hill, which is veneered by carbonate-bearing loess overlying the granite. It’s still today a highly respected site, though just one of several, most of which are located directly on granite. But Busby was convinced. We are not told how he reconciled his new idea with his experience of the gravels of Bordeaux or what he might have thought if his European itinerary had taken him to places with different geology. But as it is, Busby could not be clearer: “[T]he soils of all vineyards producing dry wines of superior excellence are strongly calcareous.”

Busby says nothing about wine character or flavor; he is talking throughout about the quality of the wine, vin ordinaire versus fine wine. He explains what this means in practice to the French: Ordinary wine is drunk with ordinary meals, in tumblers and usually mixed with water; by contrast, fine wine is drunk pure, and from wine glasses. And according to the converted Busby, to produce fine wine—anywhere—you need calcareous soils.

But really it’s all in the winemaking

It’s surprising that Busby didn’t make more of the effect of soil on wine taste, because he was writing at a time when plants were still thought to be made of soil. (Photosynthesis wasn’t recognized for another half-century.) Grapevines formed themselves by taking water and associated matter from the ground—the belief of the time went—and the resulting fruit, also made of this soil material, transformed into wine.

This was probably Busby’s understanding; he wrote of vine roots being “in search of juices which are appropriated by the plant.” He certainly thought that manure in the vineyard transmitted taste to the finished wine; it often led to a “bad flavour,” he reported, especially “if the dung of cows, and still more, that of pigs” was used. But there is nothing about the soil itself affecting taste. In other words, later works that cite Busby to support the notion that geology can be tasted in the wine have to derive from that terse and anomalous single sentence back in his 1825 Treatise.

Despite all of this, however, Busby followed his pronouncement on the supremacy of calcareous soil by then going on to play down the importance of vineyard soil. Busby detailed how true wine excellence is achieved by careful management of the vineyard, optimal harvesting, and assiduous attention to vinification and cellaring. This is how “the vineyards of a few individuals acquired a reputation which has enabled the proprietors to command almost their own prices for their wine.”

Today’s marketing commonly promotes the specialness of a wine because of the uniqueness of the soils—about the only factor that can’t be replicated. And back in his time, Busby felt that this same idea was being used to deter rival producers. But, he says, “there is more of quackery than of truth in this.” He continues, “[I]t was evidently the interest of such persons that the excellence of their wines should be imputed to a peculiarity in the soil, rather than to a system of management which others might imitate.” Plus ça change…

The mirage of Kirkton, “Busby’s vineyard”

Presumably, Busby’s pronouncements on vineyard soils carry added weight today because of the perceived stature of the man as a pioneering wine authority. But in view of Busby’s dearth of actual involvement with wine, it’s as though, with time, a veneer of mythology has grown up around him. The thought is illustrated by the celebrated “Busby’s vineyard” at Kirkton, regarded by some regard as the cradle of Australian wine.

In 1828, William Kelman planted vines at Kirkton, on the higher, less clayey parts of the estate, presumably inspired and guided by his brother-in-law’s writings. In 1830, he produced wine, and the business took off. In time, Kelman’s son James took over and won awards both in Australia and abroad for his wines. Apparently, although James himself was teetotal, they were “very inebriating”! He established the much-loved local tradition of inviting folk to celebrate each vintage at Kirkton with a banquet, picnics, and “athletics events with prizes.”

These were the glory years of Kirkton and, in a way, an expression of Busby’s vision of the viticultural possibilities in Australia. In 1914, it was bought by the respected Lindeman family of the nearby Cawarra Estate, and in 1930, with some of the original plantings still thriving, the Lindemans held a grand celebration of 100 years of winemaking at Kirkton. A hundred gallons of Kirkton “Chablis” and a hundred gallons of “Burgundy” were served; they even managed to produce some bottles from the very first vintage. But that was to be the swansong for Kirkton.

The following year, the Lindemans decided to pull out of the Hunter Valley, and the Kirkton land then passed through a series of owners, none of whom were interested in viticulture. The heritage vines were pulled up and the house demolished; all that was left was the cellar. The cellar floor still had some of the original bricks once made by convicts from nearby red clay, some carefully marked with a letter K (for Kelman? Kirkton?), but not long ago even these were taken away, for some ignominious use elsewhere. All that is visible today among the rough pasture is a single flat grave slab, weathering badly but with some Busby and Kelman family names just visible. Even the very name Kirkton has now been usurped by another property.

But in a way, that there’s hardly anything to see there today adds a veil of mystique to the place, an invitation to use the imagination. These days (according to the present owner), the site of “Busby’s vineyard” is a place of pilgrimage for wine enthusiasts from all over the world. After all, “James Busby’s name is synonymous with all that is great about Australian wine,” one web page proclaims, and there’s a Kirkton Wine Club, “named in honour of […] Kirkton” and “its intrinsic association with James Busby.” It all enhances the status of Busby—and hence the gravitas attached to his words.

Unfortunately, the written records suggest a different picture. The Kirkton vineyard was, as we have just seen, planted and operated throughout by the Kelman and Lindeman families. Successful it may have been, but so were plenty of other Hunter Valley estates. Nor was it the first. George Wyndham, for example, planted vines just to the east at the same time, and Thomas Webber was producing wine less than 15 miles (20km) from Kirkton in 1828.

What are often referred to as James Busby’s land and James Busby’s house actually belonged to father John Busby, who retired and died there—hence his and the Kelman names on the still existing grave slab. James Busby was later allotted land fairly near Kirkton, but there is no record of his ever having done anything with it, apart from selling it on in 1832.

Conceivably, Busby visited family at Kirkton, though his family relations were often strained. It would have been a time-consuming journey from Sydney for the busy man; surely there would be a mention in his fastidiously detailed writings? And Busby felt Kirkton unsuitable for viticulture. He wrote to a friend (Busby was an inveterate letter writer) that, “I cannot say that I think it prudent of Kelman to launch into a plantation of 10 acres of vines before he has proved the capabilities of the soil. I think it unlikely that his wine will ever be above the Vin Ordinaire.”

The fact is that there is no record of Busby ever having been to Kirkton, let alone working vines there and making wine. (There seems to be no record of his having made wine anywhere.) Nevertheless, Kirkton has been called “an icon” and “Australia’s most important heritage site.” One visitor remarked that standing at Kirkton paying homage to Busby “sent shivers down my spine.” Although these perceptions are hard to square with the evidence, Busby himself undoubtedly would love them.

James Busby tackles New Zealand

James Busby’s writings on viticulture were without question genuine attempts to encourage and advise the infant wine industry in New South Wales and elsewhere. Together with the spread of his propagated vine cuttings, they were highly effective. For Busby, though, they were just part of a wider agenda.

One broader aim was to encourage the drinking of civilizing wine rather than inebriating spirits. The very first page of the Manual spells it out; the book’s ultimate purpose is to “promote the morality of the lower classes.” Another aim was to improve agriculture in general in the colonies and so lessen their dependency on the mother country. Hence his advice in the Manual on producing raisins, almonds, figs, and so on. In other words, Busby saw himself as a colonial improver. But even this was part of a more fundamental motivation, one that drove Busby throughout his adult life: the need to acquire status, improve social standing—to be admired. Expounding on wine was part of this striving.

The trip to London that enabled Busby to visit France and Spain was made primarily for him to try to persuade the colonial powers-that-be that the fledgling, ungoverned, and anarchic settlements in New Zealand needed the presence of a person of distinction and authority. Oh, and he could be just that person (even though he had never been there). His machinations worked, and Busby got himself appointed as official British “resident” in New Zealand. This was only eight years since he had first arrived in Australia from Scotland, so Busby, still only 30 years old, had certainly done well for himself. (He did, though, have some concerns about his new position: Would his house be suitably imposing and built of brick? Would his uniform be a properly embroidered and tasseled tailcoat, with plumed hat?)

A great deal continues to be written about the doings that followed Busby’s appointment and what it all means today for New Zealand—for example, The Rise and Fall of James Busby, by Paul Moon (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020). I merely note here that Busby did plant a “grapery” next to the residence he had built at Waitangi, in the North Island’s Bay of Islands. (Because of it, even though Busby’s weren’t the country’s first vines, he has been dubbed by some “the father of New Zealand wine.”) But Busby seems no longer to have been very interested in wine. Among the vast amount of material he turned out during his nearly 40 years in New Zealand, there is no mention of wine, viticulture, or vineyard geology.

Busby’s house still stands, on the Waitangi Treaty grounds, but it presently has just a few straggly vines growing behind it. (For what it’s worth, the soil at Waitangi is, just as at Kirkton, alluvium with patches of the clay that Busby had once derided. But fittingly, it overlies a bedrock of what is effectively New Zealand’s national rock, graywacke.)

Evidently Busby’s cantankerous nature traveled to New Zealand with him, for soon he was making enemies all over again and getting involved in new legal squabbles. And over time, his always vague official authority progressively drained away, and he became heavily in debt as successive businesses failed. Moreover, his eyesight continued to deteriorate. Thus in 1871, Busby traveled to London for cataract surgery. The operation was successful, but while convalescing he caught acute bronchitis, which soon worsened. Shortly afterward, far from his adopted lands, James Busby died—according to the official record, from “congestion of the lungs.”

There seems to have been no mourning on the other side of the world, scant mention in the newspapers, and no memorials. And that is why this important and influential individual comes to be buried unceremoniously in a suburban London cemetery. And there he lies still, in his solitary grave, disillusioned, unfulfilled, embittered, and lonely. Or as they say in Scotland, anerly.