There was a time when Carcavelos wine was something of a British household name. At the end of the Georgian era (early-19th century), it was relatively common to find the words “Lisbon” and “Calcavella” engraved on the decorative silver tags designed to identify the wine served from a decanter. Both were fortified wines, the Port of Lisbon briefly competing with Oporto (Porto) for the shipment of wine from their respective hinterlands. “Lisbon” is no longer (other than as the much larger Vinho Regional “Lisboa”), but Calcavella is making a welcome return as a fortified wine under its modern-day name.

Situated close the mouth of the Tagus, Carcavelos is a now a coastal suburb of Portugal’s capital city, just 12km (7.5 miles) west of Terreira do Paço (“Black Horse Square”) that marks the center. The surfing crowd who regularly congregate on the broad sandy beach are blissfully unaware of the trials and tribulations of this historic wine region, which was driven to the point of extinction in the late-20th century. Although vines have been planted along the Tagus (Tejo) estuary since the 14th century, Carcavelos was made famous in the 18th century by the Marquês de Pombal, Portugal’s autocratic Prime Minister under José I, who had his then out-of-town residence at Oeiras. Pombal is celebrated for enacting the first modern demarcation of the Port region in 1756, but when it came to Carcavelos, he deliberately flouted his own rules. Pombal apparently sold grapes from his estate to Port producers, and may well have blended Port with wines from his own estate. At the time, Calcavella was a rich, amber-colored fortified wine that regularly appeared alongside “Lisbon” at Christie’s early London auctions, and the two wines were probably very similar in style. John Croft, writing in 1788, described between 4,000 and 5,000 tuns of “Lisbon” being imported to England, “all promiscuously called Calcavella.” A consignment was sent by José I to the Court of Peking, no doubt at Pombal’s instigation.

Calcavella, then Carcavelos, continued to be shipped to England during the 19th century and enjoyed a period of vogue in the aftermath of the Peninsular Wars when Wellington’s troops had been stationed in the hinterland around Lisbon. Later in the century, phylloxera put paid to exports. Records show that production fell to just 12 pipes (6,600 liters) in 1867, but by the 1930s it had recovered to a modest 40,000 liters of wine a year.

Carcavelos was demarcated in 1908 to take in the then villages of Oeiras, Parede, São Domingos de Rana, and the town of Carcavelos itself, all of which had substantial areas of vineyard. Now a DOC [DOP], the region has been enlarged to include the coastal strip between Paço de Arcos and the outskirts of the resort town of Estoril. In the meantime, however, large areas of vineyard have been lost to urban development, as Lisbon has expanded westward along the Tagus estuary. The heart of the region was around Sassoeiros, but since the 1950s, properties with bucolic-sounding names like Quinta de Bela Vista, Quinta das Rosas, and Quinta das Vinhas have been supplanted by housing estates. There is one urban area named Bairro Além das Vinhas (“Estate beside the Vines”), even though the vines are no more. Vines are now being planted on roundabouts as a nod to the wine region.

The civic saving of Carcavelos

It is now hard to trace the true character of Carcavelos wine, since there wasn’t much in the way of consistency in the 20th century. A fleeting revival of the wine took place in the 1980s, when a new vineyard was planted at Quinta dos Pesos, at Caparide behind Estoril, but most of the vines were uprooted a decade or so later. Around the same time, one of the last of the traditional estates, Quinta do Barão, which once belonged to the Counts of Riba d’Ave, fell prey to urban development. That would have been the end for Carcavelos, but for the intervention of Oeiras town council in 1997. Joining forces with the Estação Agronómica Nacional, they restored the vineyard on Pombal’s old estate, and from 2001 they began producing wine again, marketing under the brand name Villa Oeiras. Not to be outdone, Cascais town council is also supporting a project in its patch, which includes the suburb of Carcavelos itself.

There are currently 32ha (80 acres) of vineyard within the Carcavelos DOC, with 23ha (57 acres) on the Marquês do Pombal’s old estate. A modern winery (Adega do Casal da Manteiga) has been created from a former dairy (hence manteiga, meaning “butter”), with the cellars of the old palace used for aging the wines in cask and barrel. The property is open for guided tours on certain days of the week and can be reached easily by train from the center of Lisbon.

The mild Atlantic climate lends itself to the production of fortified wine. The coastline faces due south, and a series of shallow valleys offer natural shelter from the Atlantic westerlies that buffet the west-facing coast just around the corner from Cascais. Both red and white grapes may be used to make Carcavelos. The reds are Castelão and Preto Martinho, supplemented by Trincadeira and Amostrinha, alongside white grapes Boal Ratinho, Arinto, and Galego Dourado. Of these, Galego Dourado seems to be the most distinguished and is now being cultivated with considerable success for unfortified whites on the Alentejo coast to the south of Lisbon. The calcareous soils and maritime climate lend acidity, which is considered essential for the character and the aging of the wine. Picking now begins as early as mid-August to retain natural acidity, although Arinto and Ratinho are far from short of it.

In the past, the grapes were foot-trodden in lagar and fermented dry before being fortified with grape spirit up to at least 17.5% ABV. Residual sugar may not be more than 150g/l, with most of today’s wines registering RS levels of around 100g/l. According to António Maria de Oliveira Bello, who described Carcavelos toward the end of its heyday, the wine was produced in two styles: seco and meio seco. The former was apparently sold with a minimum of 18 years of age and the latter with 11. Both are described as aveluado—“velvety.”

Carcavelos reborn and reinvented

Carcavelos is currently reinventing itself and writing its own rules, with blended wines bottled at seven and 15 years of age (“Superior”), and sporadic single-harvest or colheita wines when quantity and quality permit. In future, when stocks permit, it is planned to bottle aged wines at 20 and 30 years, in parallel with Port and Madeira. There are now around 2,000 barrels in stock. The fortifying aguardente is 77% strength (akin to that used to fortify Port), with producers preferring to age a portion of the spirit in wood for eight months before fortifying to make the wine smoother and more mellow from the outset. Some spirit originates from nearby Lourinhã. There are currently wines made entirely from white grapes, a blend of red and white, and (in the case of the Adega de Belém urban winery), a wine made from pure Castelão. I have to say that I didn’t find the latter very tipico (to use a Portuguese word), being more akin to a young Tawny Port. True Carcavelos has been described as being “between a Sherry and a Madeira” in style. On the basis of the wines tasted below, this is a fairly apt summary. In fact, it was not unknown for the wines at Quinta do Barão to be subject to some rudimentary estufagem (heating in the sun). Today’s Carcavelos must be aged in wood for a minimum of two years, though most producers are aging their wines in French and Portuguese oak barricas of varying sizes for considerably longer. It is felt that wines made from red grapes need longer in wood than those made from white grapes. Larger chestnut casks are also used. All producers are now obliged to have a conta corrente (stock account) with the local CVR, which issues seals of approval. Like Madeira with its acidic base, Carcavelos clearly needs age.

Most of the wines below were tasted in Lisbon at the Instituto Superior de Agronomia in February 2024, in what must have been the first comparative tasting of Carcavelos for many a year. My thanks go to Jorg Lewerenz for inviting me, and to Rodolfo Tristão for leading this rather remarkable tasting. I have added more recent notes on the 7-year-old, 2014 Colheita and a 1997 Colheita from a tasting at the Villa Oeiras adega with winemaker Alexandre Lisboa. He is conscious of his pivotal role in restoring the region’s reputation: “We are aware of our heritage, and we are creating these wines for future generations.” Old bottles of traditional Carcavelos can still occasionally be found in specialist Lisbon wine shops, but look out for the new generation of wines from Quinta do Corrieira and Villa Oeiras, both of which represent the future of Carcavelos.

Tasting Carcavelos

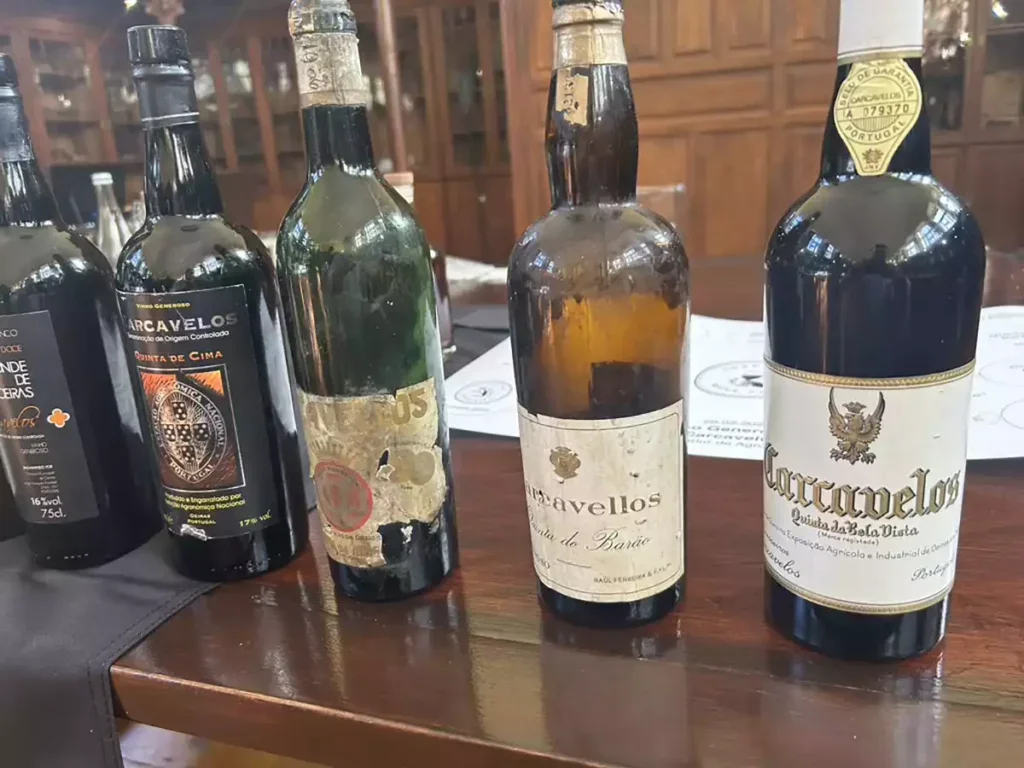

“The first comparative tasting of Carcavelos for many a year,” in 2024. Photography by Richard Mayson.

Villa Oeiras 7 Anos

A blend of white wines aged in seasoned French and Portuguese oak casks for 7–9 years. Lovely, golden, orange-amber color; still showing spirit on the nose, with orange-peel aromas and a touch of toffee; gloriously smooth and fresh, with citrus-toffee complexity, gentle mouthfeel, and a clean, breezy finish. | 88

Villa Oeiras 15 Anos Superior

A 15-year-old blend from the three principal white grape varieties, fortified with aguardente from Lourinhã, aged in Portuguese and French oak as well as chestnut. Lovely, golden amber color, with a green glint; heady maritime nose, salty citrus, candied peel, and a hint of toffee; similarly fresh crystalized-lemon and dried-apricot fruit, good balance (100g/l RS), fresh and nicely defined. | 91

Villa Oeiras Colheita 2014

This is the most recent single-vintage Carcavelos, shortly to be launched on to the market. Pale golden amber, with a glint of olive green on the rim; gently toasted dried-apricot aromas and flavors, with lovely mouthfeel, delicate richness mid-palate (95g/l RS), and on to the finish with a hint of saline butterscotch, now beautifully melded and harmonious with age. | 92

Quinta da Corrieira Colheita 2012

The launch of a wine from a small property at Barcarena, 150m (500ft) above sea level about 5km (3 miles) inland from Carcavelos itself, with tremendous views over the Estoril coast. Made from a roughly equal blend of Galego Dourado, Arinto, and Ratinho, the specifics of the vinification and aging process for this have already been lost due to the indisposition of the previous owner, making this something of mystery wine. The property was only acquired by the current owner, Jorg Lewerenz, in 2017. Pale amber, with a green glint; delicate floral perfume, honeysuckle, vaguely nutty, too, with a hint of dried apricot; sweeter on the palate than the nose suggests (about 90g/l RS), dried-apricot sweetness balanced by acidity, leading to a lithe, elegant finish, delicate and honeyed. | 92

Quinta dos Pesos 1995

This property at the back of Estoril kept Carcavelos alive during the 1980s and ’90s. A blend of white and red grapes, the later accounting for about 35% of the blend and including Castelão and Espadeiro, bottled in 2023 for Howard’s Folly (with Australian David Baverstock in charge of the winemaking). Deep orange-amber, olive-green rim; rich and heady on the nose, with a touch of butterscotch and molasses, lifted and almost Madeira-like in style; similarly rich and textured on the palate, tawny marmalade in character, with a saline streak, quince and boiled sweets on the finish. Very good indeed. | 95

Carcavelos 1997 Colheita

A wine made from grapes grown by the Estação Agronómica in Oeiras but made at the Dois Portos adega near Torres Vedras, still in cask. Lovely, deep golden amber, with a complex, slightly lifted, mellifluous character on the nose and palate, combining creamy butterscotch richness and candid-peel freshness with just a hint of chocolate. Rather glorious. Just one pipe remaining. | 94

Quinta da Ribeira de Caparide 1989

A blend of red and white grapes from a property near Estoril. Pale-to-mid- amber, rather cloudy; smells of rather poor-quality aguardente, with a backdrop of rather dusty dog biscuits; better on the palate, savory, in a drier style, saline but quite neutral, with a touch of toffee and carame on the rather extractive finish. Unappealing. | 80

Conde de Oeiras

A blend of wines from 1997 to 2004, bottled in 2009. This was the first wine to be bottled by the Villa Oeiras project, backed by the town council. Mid-amber-orange, with a green glint; strangely roasted and rather oxidized on the nose, singed and rustic; rich on the palate, semi-sweet in style, with 110g/l RS, rather dusty dried apricots (sweet and savory), with some texture and a sultana-like finish. Disjointed; doesn’t quite gel. | 84

Quinta de Cima

An experimental wine from the late 1980s/early 1990s, made at Torres Vedras from grapes grown in Oeiras, the vines having been planted in 1983. Pale mahogany, with a green-tinged rim; honey and orange blossom on the nose, grapey, too, “like an old Moscatel,” as one taster said; very rich and sweet in style (probably close to the maximum 150g/l RS), quite elegant, with peachy fruit and medicinal sweetness on the finish. This seems to have aged rather well in bottle. | 88

Quinta d’Algoa 1906

These vineyards have long disappeared under a housing development. There is a public garden named Algoa close to the modern-day center of Carcavelos. Deep, bright amber, with an olive-green rim; delicately maderized on the nose, with a touch of rancio, lifted and high-toned, with a touch of woodsmoke; a similarly delicate, off-dry, savory-smoky character on the palate, notable acidity, but more in the style of Amontillado Sherry than Madeira, with a similarly dry, austere finish. | 91

Quinta do Barão No 1

This is a wine from the 1920s, when this property bottled wines numbered 1, 2, or 3, reflecting increasing sweetness. Barão continued to produce wine until 1988 (bottled as Ultima Reserva, Last Reserve), when the estate was divided in two by a feeder road. The adega still stands abandoned but there have since been various projects for redevelopment. Mid-deep mahogany, with an olive-green rim; wild, funky, rather woody nose; a delicate (fragile even) saline character, with crystalized fruit (Elvas plum) and a rather abrupt, austere finish. A fascinating wine, if very difficult to score. | 87

Quinta da Bela Vista

A wine around 80 years old, thought to be made principally from Galego Dourado. The estate ceased production in 1969, and the wine remained in vat until it was removed and bottled in 1991 by Carlos Pereira da Fonseca of Quinta de Sanguinhal at Bombarral. Around 9,000 liters were bottled. Pale- to mid-amber in color; delicate, clean, if a bit non-descript on the nose, vaguely nutty; soft, dry, and quite elegant (only about 10g/l RS), with a soft, slightly grapey finish. There was some significant variation between bottles though. | 87