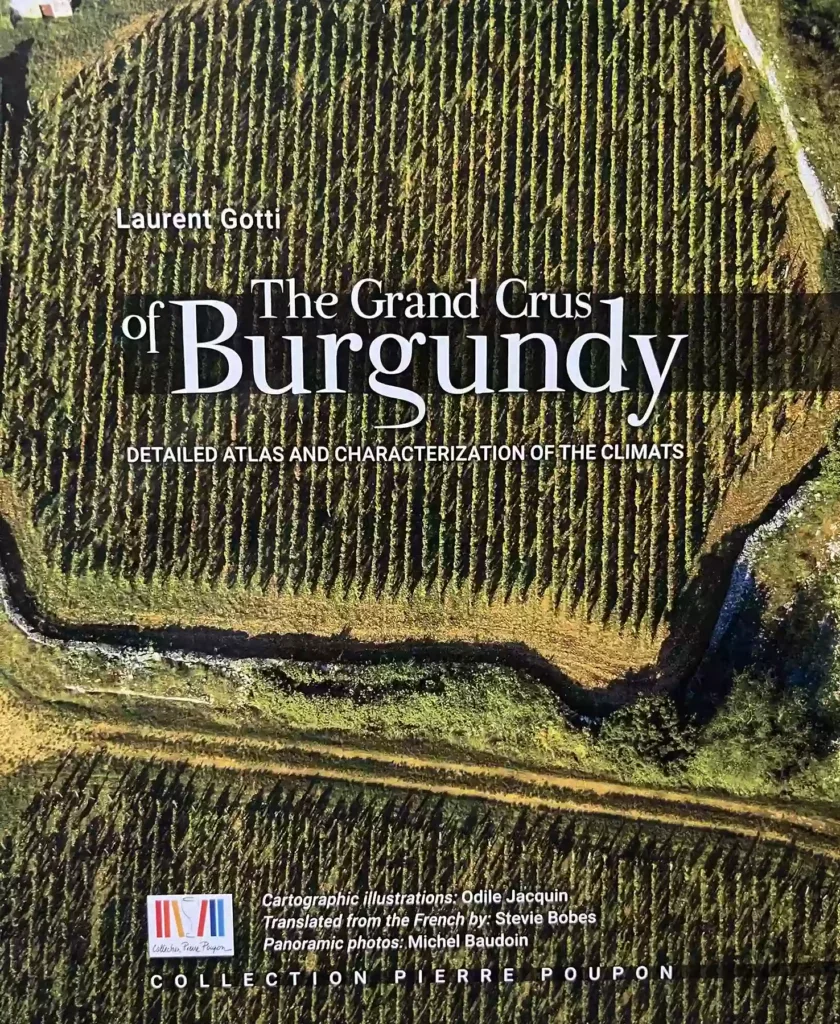

Raymond Blake reviews The Grand Crus of Burgundy: Detailed Atlas and Characterization of the Climats by Laurent Gotti.

As howlers go, the designation of the Romanée-Conti vineyard as a “Vosne-Romanée premier cru” on pages 208 and 209 of this otherwise authoritative book is quite astonishing. The most famous vineyard on the planet downgraded at a stroke… and the same indignity is also visited on Richebourg and La Grande Rue, the other neighbors of Romanée-St-Vivant, the grand cru mapped on those pages. Thereafter things can only get better—and they do.

This is a book to be perused rather than read, to be mulled over and thought about, with a magnifying glass to hand when the naked eye is defeated by the level of detail in the maps—necessitated by the extraordinary parcellation of vineyard ownership and the challenge of accurately illustrating it. If any wine region deserves to be mapped thus, it is Burgundy, specifically its Côte d’Or heartland, with the seven Chablis grand cru climats included in one map to complete the picture. And if you give it the attention it deserves, it rewards you by way of deeper understanding and insight, helping to clear, though never fully dissipate, the fog of mystery that often clouds the fabled names and that only serves to foster their renown.

Grand Crus is more than a compendium of maps, the clue being found in the second part of the title: Detailed Atlas and Characterization of the Climats. Laurent Gotti sets out his stall in the first paragraph: “The grand crus of Burgundy constitute a unique model of world-renowned terroir-based viticulture. To identify precisely, however, the conditions of their emergence in this specific place is more complex than it seems. It is commonly accepted that natural conditions, soils, subsoils, climate, etc are the most important factors, but in many cases their delimitation can hardly be explained solely by the generosity of nature. In many cases, the perseverance of people, over the centuries, deserves to be given a central place in explaining the level of excellence achieved by these wines.”

That final sentence chimes with the central tenet upon which the Côte d’Or’s successful application for UNESCO World Heritage status was based—that the celebrated slopes’ natural potential was harnessed by the hand of man. Without that intervention, the land would have remained mute, much like a musical score waiting for an instrument and a performer to reveal its glory. The hand of man can be fickle, however. At a tasting earlier this year of some three dozen grand cru wines as part of Les Grands Jours de Bourgogne, a marvelously well-organized biennial week-long tasting marathon, I was left unconvinced by too many of the wines. There were a couple of standouts, which only showed up the others—all perfectly decent iterations, but when it is known that they are grand cru, expectations are inevitably raised, a circumstance then compounded by knowing that the price is never going to be low. Jasper Morris MW, in his magisterial Inside Burgundy, captures what should be the essence of a grand cru: “A grand cru worthy of its name should have a clearly definable character of its own which is separate from—and grander than—the prevailing style of the village […].” It was the lack of this “clearly definable character” that drew me up short in that tasting.

A paean of praise

This book, which is largely a paean of praise to the grands crus, could use a little more acknowledgment of that issue, though Gotti calls it correctly when considering the 50ha (125-acre) expanse of Clos de Vougeot: “Clearly, the terroirs of Clos Vougeot are not all the same. This statement is true for any climat. However, more than anywhere else, the classification of the entire Clos de Vougeot as grand cru is controversial.” The classification may be controversial, but the more common talking point is the division of those 50ha among 80 different owners, giving an average holding of only 0.625ha (1.54 acres). Whenever the minute parcellation of the Côte d’Or’s prime vineyards comes up for discussion, Clos de Vougeot is wheeled out for a ritual beating. I say, Not so fast, because thanks to the wealth of information contained in these pages (the product of much tedious graft, I’ll aver), numerous other examples of the parcellation are ready to hand.

Clos de Vougeot’s near neighbor Echézeaux manages to fly below the radar in this regard, despite its 38ha (94 acres) being divided between 59 owners, to yield an average of 0.64ha (1.58 acres). Indeed, the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti holding of 4.67ha (11.54 acres) there is equivalent to the total of the smallest 21 holdings together. And traveling south to the Côte de Beaune, we find that both are topped in terms of minute subdivision by Bâtard-Montrachet, its near dozen hectares (30 acres) spread among 41 owners (average 0.29ha [0.72 acre]), only one of which, Domaine Leflaive, owns more than 1ha (2.47 acres), while 24 producers make do with a holding of 0.2ha (0.49 acre) or less. At this level of pixelation, the hand of man must be exceptionally dexterous, for this is winemaking in miniature, sometimes with a barrel made to fit the quantity of wine produced each year. Whether this is the best way to harness the grands crus’ potential is questionable.

This level of detail is what makes Grand Crus compelling, almost addictive reading for any wine lovers obsessed with vineyard minutiae—a charge to which I plead guilty—but that is not its only strength. Added gravitas comes by way of myriad quotations from well-respected vignerons such as Marie-Christine Mugneret-Gibourg, Jeremy Seysses, Cyprien Arlaud, and others. Mugneret-Gibourg on Clos de Vougeot: “We harvest it in the middle of the harvest, early in the morning, before the arrival of visitors to the château […]. It can be left in the tank for an extra 24 hours without taking any great risks. It absorbs new oak quite well during maturation.” Seysses on Clos de la Roche: “The Clos de la Roche can be vinified without difficulty. It is a well-behaved child with a fairly constant temperament. In warm vintages, it does not lose its balance. In cold vintages, it still manages to mature. Grand crus are ultimately forgiving terroirs.” Arlaud on Clos St-Denis: “Clos St-Denis reaches an extreme level of emotion after several years. And this amplifies with age. The grace it can achieve is not widely known. It’s the Musigny of Morey-St-Denis.”

Grand Crus is a celebratory treatise that is hugely useful, but it would benefit from a little leavening of the good news. When mentioning the Hill of Corton’s 160ha (400 acres) of grand cru, Gotti declares, “[N]o other sector of the Burgundy wine-growing area can boast such a rich endowment in the highest category of the regional hierarchy.” It is a boast that could do with trimming.

In vinous terms, this book is a wine from a warm vintage made from ripe grapes whose acidity was on the low side. Even so, I look forward to many more hours perusing and poring over it, teasing out the detail of this vineyard or that. Though its appeal will be limited, it is sure to become an indispensable reference for anybody deeply interested in Burgundy.