To mark the centenary of the village’s ascent to AOC status in May, 1923, growers in Mercurey hosted a year of celebratory events. Raymond Blake looks back on some of the highlights of the festivities and charts the evolution of the appellation over its first 100 years.

David Lloyd George, the “Welsh wizard,” was noted as a wily operator, yet his skills at the negotiating table hit the buffers when trying to deal with Irish Nationalist leader Éamon de Valera in 1921, leading him to conclude: “Negotiating with de Valera is like trying to pick up mercury with a fork.” To which de Valera memorably replied, “Why doesn’t he use a spoon?”

No such difficulties attend the appreciation of the wines of Mercurey, the Côte Chalonnaise village and appellation that takes its name from the Roman god of business and trade. Both the whites and reds have a direct, immediate appeal; many boast bold flavors, though the heavy-shod reds of old are less dominant than they used to be. Those were wines of substance rather than grace, and examples that cleave to that template can still be found today, but a more dexterous winemaking touch is also in evidence. In the whites, the wines that avoid what I call the “tropical fruit trap” are the ones with enduring attraction, thanks to a less lush, crisper palate profile.

Mercurey has long been seen as the engine room of Burgundy’s Côte Chalonnaise, a situation acknowledged by the fact that the Côte was once called the Région de Mercurey. That designation didn’t stick, however, and it is now named for the nearby city of Chalon-sur-Saône, which lies a little to the east of the Côte. Its history can be traced back some 1,500 years; not quite to Roman times, though Julius Caesar did write about the god Mercury in his Gallic Wars: “The god [the Gauls] worship most is Mercury: his statues are the most numerous, they consider him as the inventor of all arts, he is the god who shows them the way to follow, who guides the traveler; he is also the most efficient god to help you earn money and he protects trade.”

Today, the village of Mercurey is neatly divided by an arrow-straight main thoroughfare, predictably named Grande Rue, which follows the path of an original Roman road that was part of an important trade route running up from the Rhône and on toward the Loire. So, perhaps it is not too fanciful to speculate that, with such strong links to trade and Rome, the village was named to curry favor from the relevant god.

Notwithstanding this ancient lineage, Mercurey’s modern history begins a tad over a century ago, on May 30, 1923, when a court ruling of the previous day, which created the Mercurey appellation d’origine contrôlée, was made official. The ruling was the result of a court case taken by local winemaker Edouard de Suremain, who sought legal protection for the name Mercurey—specifically to prevent winemakers in the neighboring villages of Rully and Givry from labeling their wines as Mercurey to give them greater visibility, thus boosting sales. In this, Mercurey was ahead of the game, for the whole concept of appellation contrôlée, with its definitions, strictures and regulations, was only beginning to take shape. It would be more than a decade longer before the nationwide system, still largely in place today, was established on a firm legal footing.

Whatever celebrations took place to mark the court victory cannot have been too raucous or exultant, for these were grim times for Mercurey. All over France, phylloxera had wrought devastation in the vineyards, while World War I brought devastation of a far more tragic nature. Any glimmer of recovery from those catastrophes had to contend with the far-reaching effects of Prohibition in the United States, while, particular to the Côte Chalonnaise, the decline of the local mining industry closed off a strong local market for the wines. As the 20th century progressed, further challenges came by way of worldwide economic depression and another world war. Recovery from this catalog of woe was snail’s-pace slow, but the tale finally took an upturn in the latter decades of the 20th century, and so far the first quarter of the 21st has been largely a good-news story, the looming challenge of climate change notwithstanding.

Extended and worthy centenary celebrations

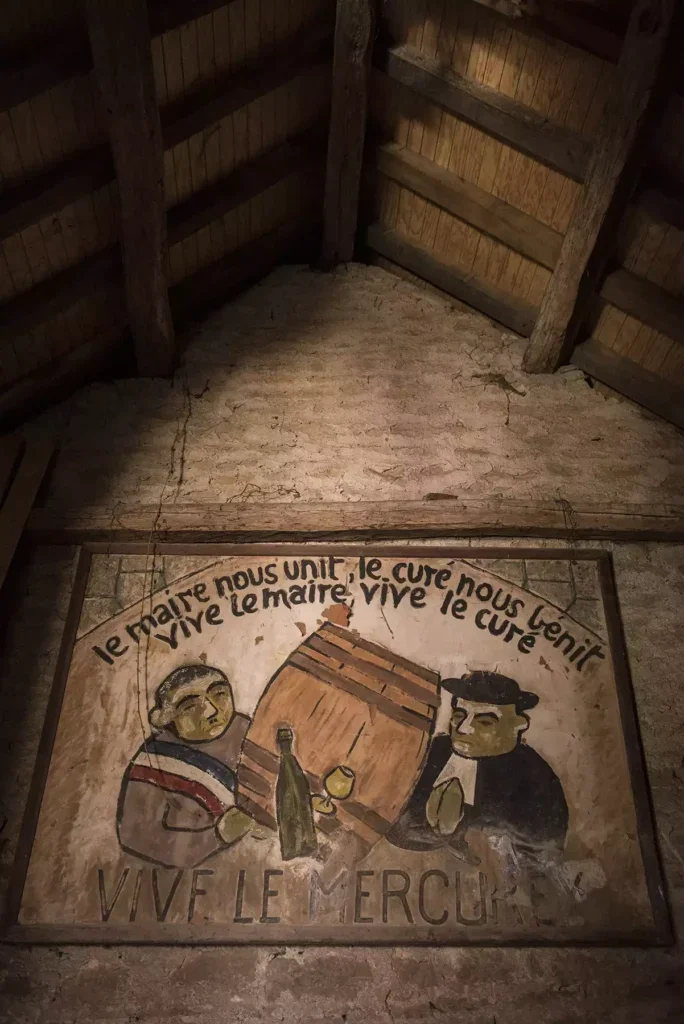

Thus, the good burghers of Mercurey (Les Mercurois?) were well placed to celebrate the 2023 centenary of the court’s ruling and did so by way of a year-long series of events that started with a commemorative ceremony on the exact hundredth anniversary of the decree that granted appellation status. Then followed a Grande Fête in July 2023 that featured every manner of activity and entertainment, including demonstrations of artisan skills from yesteryear, such as those of the farrier, the blacksmith, and the clog maker, while also looking to the future and the use of drones, RFID (radio frequency identification) chips for bottles, and GPS-guided tractors.

The celebrations culminated in a more structured commemorative weekend in March 2024, which started with a grand dinner billed as a “Four Hands, Five Stars” event—the creation of two big-name chefs who could lay claim to a quintet of Michelin stars between them. They were Eric Pras of Restaurant Lameloise in Chagny (Meilleur Ouvrier de France 2004), with three stars, and Cédric Burtin of Restaurant l’Amaryllis in St-Remy. The dinner was held at the Abbaye de Maizières near St-Loup-Géanges, and the chefs’ skills shone brightest early in the evening by way of a magnificent series of canapés—escargot de Bourgogne, succette de foie gras, tartelette de boeuf & tartare de boeuf—each a flavor jewel that beguiled the taste buds, though the foie gras topped them all. A pair of wines accompanied them: Domaine Patrick Guillot 2022 Mercurey Blanc Les Morins and Domaine Faiveley 2022 Mercurey Premier Cru Rouge Clos des Myglands. The former was a pleasant wine on its own, thanks to ripe, fresh fruit, but the latter matched better with the canapés, where its lovely bite of cherry-raspberry fruit counterpoised the broad array of flavors on offer.

The canapés proved to be the gustatory highlight of the evening, for, truth be told, events such as this are logistical rather than culinary triumphs. In terms of conviviality and joie de vivre it could not have been bettered, but the series of impressively crafted dishes struggled to capture the diners’ attention, save for one: the St-Jacques de plongée snackée, butternut fermentée, caviar Kristal Caviari, sauce barde de St-Jacques, huile de corail, poudre de citron noir d’Iran. It was a culinary triumph, replete with opulent, luxurious flavors and a satin texture that might have overwhelmed the taste buds had the Domaine de Suremain 2019 Mercurey Premier Cru Blanc En Sazenay not provided a gentle whip hand of acidity to corral the flavors and stop them running rampant. It was followed by volaille de Bresse farcie sous la peau, jus à la cazette du Morvan et safran, which provided a satisfying foil to the Château de Chamirey 2022 Mercurey Rouge Hors Ligne rather than shining in its own right. The wine spoke in an authoritative voice and confirmed—as did the earlier Faiveley Clos des Myglands—that the 2022 vintage in Burgundy is a wonderful combination of the richness of the 2020 and the reserve of the 2021. It is a vintage to seek out.

The following day started with a visit to Le Caveau Divin, which sits at the northwestern end of Grande Rue before it swings left and heads into the vineyards. Self-described thus: “Le Caveau Divin is an innovative retail outlet in Burgundy that allows passing travelers to sample Mercurey’s wines. You can try up to 64 different wines from 44 estates and producers in this unique, comfortable setting.” The caveau opened in 2011 as a cooperative cellar and tasting venue, and as an introduction and showcase to the region, it could hardly be bettered. It uses the Enomatic dispensing system, which allows visitors to use a prepaid “credit card” to sample a host of wines, before going on to purchase their favored bottles—for the same price they would pay if buying direct from the producer. But don’t tarry there too long—there are vineyards to be explored.

Mercurey: Find your way and your producers

I am forever counseling wine lovers that only by visiting a wine region—planting your feet on the ground—can a full appreciation of its wines can be gleaned. If anything, this is truer for Mercurey than almost anywhere else, for by doing so one gains an appreciation of the convoluted topography that surrounds the village itself, sitting in stark contrast to its easily assimilated linear layout.

A glance at the map suggests that the Côte Chalonnaise is simply a continuation of the Côte d’Or, but closer examination reveals this to be only partly true. Contour lines swirl and wriggle on the page; roads mimic their frenzy. The break-up of the regular slope of the Côte d’Or, foretold in the fractured landscape around Santenay and Maranges, continues apace in the Côte Chalonnaise and is most pronounced in Mercurey, where it looks as if a god reached down from the heavens and stirred the landscape into tumbled confusion. The topography defies easy assimilation; the land bucks and heaves, and the compass swings wildly as you thread your way along the challenging roads. Getting—and keeping—one’s bearings is a challenge. Make sure the satnav is working, and bring a good map for backup.

And those roads are worthy of note. Constructed from concrete, they act as culverts thanks to a “reverse camber,” dipping toward the center rather than out to the margins to carry away floodwater after heavy rains. Soil that is washed down from the appellation’s 650ha (1,600 acres) of vineyards is captured in settling tanks so that it can be recovered and returned to the surrounding slopes. Those hectares are planted largely to Pinot Noir (550ha [1,350 acres]), the remainder being Chardonnay. They also encompass two villages, because the appellation covers not only Mercurey but also its smaller neighbor St-Martin-sous-Montaigu, whose convoluted name is seldom heard of in its own right.

Also contained within those 650ha is a generous helping of premiers crus, a circumstance that pertains across the Côte Chalonnaise. Jasper Morris MW, writing in 2021, summed up the situation: “In 1988, many more premier cru vineyards were added, using for reference such authors as Courtepée (1780) and Jullien (1816). Now there are once again plans to increase the numbers. Please don’t; the villages of the Côte Chalonnaise need fewer premiers crus, not more, so that only the best terroirs are marked out.” At the same time, I was writing that the entire Côte Chalonnaise should “dramatically reduce the number of premier cru vineyards as a statement of intent and drive for quality.” This is a similar malaise to grade inflation in the academic world; in both cases, the practice devalues the coinage and undermines consumer trust.

Thus—as ever with Burgundy—the name of the producer is paramount and should always be given precedence over vineyard and vintage. Many names were in evidence over the course of the commemorative weekend last March, when I tasted roughly a biblical three-score-and-ten wines from a couple-dozen producers. Some blundering oak made its presence felt at times, but otherwise the quality was generally good, with the best wines easily making a memorable, positive impression. A handful of favorites includes Château de Chamirey for well-structured, firm-flavored wines in both colors; Domaine Michel Juillot, where a diligent approach in the vineyard translates into notably fine flavors in the wines; Domaine du Château Philippe le Hardi (previously the Château de Santenay), whose wines have improved markedly in recent years; Domaine Meix Foulot for its ageworthy Mercurey Premier Cru Clos du Château du Montaigu; and Château de Chamilly, whose wines made a good impression courtesy of precision rather than power.

Worthy of separate note is the range of wines of Domaine Faiveley—not only for their quality but also because they can act as a conduit from the Côte d’Or to the Côte Chalonnaise, specifically Mercurey, for doubtful consumers who have yet to look south for quality and, above all, value in Burgundy. Let Faiveley take you on that journey—you will be in safe hands.